When Richard Attenborough was a teenager in 1939, his parents wanted to adopt two German Jewish girls fleeing the Third Reich. His mother Mary presented the option to Richard and his two brothers, telling them it was the right thing to do but that the decision was “entirely up to you, darlings.” Of course, the boys said yes.

For the rest of his long, accomplished life, Attenborough used the same coaxing charm to get what he wanted from producers, actors and audiences. “Attenborough was an old-school British film mogul who nailed down huge funding or casting decisions over a good lunch,” Peter Bradshaw wrote in the Guardian. “When he started work on Gandhi in the 1960s, he simply got Mountbatten [Prince Philip’s uncle] to introduce him to Nehru [India’s first Prime Minister] and took things from there.” At the end of his 20-year campaign to make the movie, he charmed the Motion Picture Academy into giving his grand, stodgy biopic Oscars for Best Picture and Director over another, far superior movie about a strong, benign outsider: Steven Spielberg’s E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial.

(READ: Richard Schickel’s review of Gandhi by subscribing to TIME)

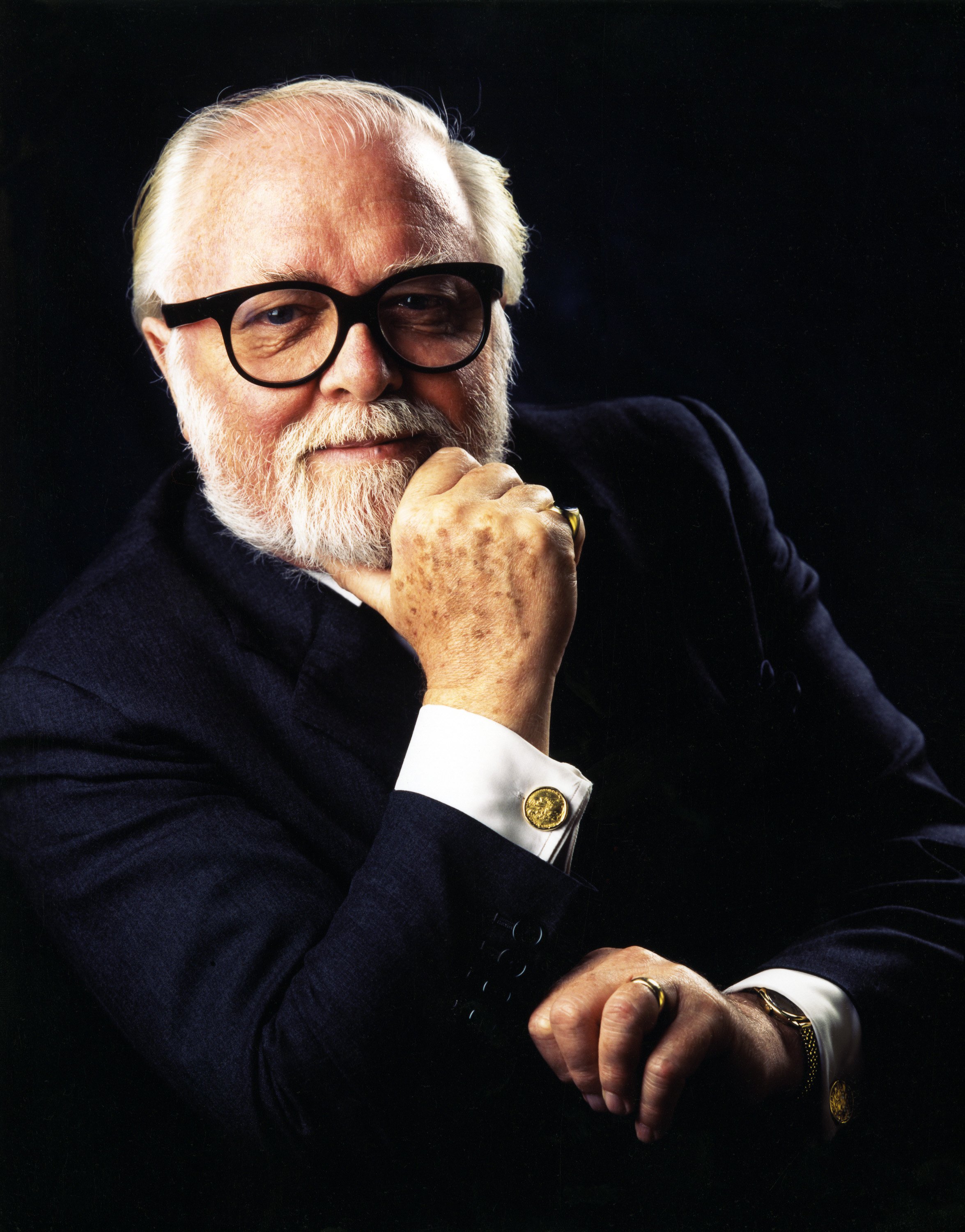

Attenborough, who died on Aug. 24 in London, five days before his 91st birthday, knew everyone, from assistants on movie sets to Princess Diana, whom at Prince Charles’ request he coached in public speaking, turning Shy Di into a figure of poised charisma. Diana — everyone — called him Dickie, or, as the official honors piled up, Sir Dickie or Lord Dickie. He had a name for them too: “darling,” his mother’s favorite endearment for her boys. “At my age,” he said in his later years, “the only problem is with remembering names. When I call everyone ‘darling,’ it has damn all to do with passionately adoring them, but I know I’m safe calling them that. Although, of course, I adore them too.”

The famously affable Attenborough had sworn off his 30-year acting career when he became a director, but Spielberg lured him back in front of the camera to play the entrepreneur John Hammond in the 1993 film of Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park. In the book, Hammond was a fiendish Frankenstein of capitalism, whose scientists had revived dinosaur species to stock his crackpot-genius idea of a prehistoric theme park. But Spielberg made Hammond a visionary with a kid’s reckless enthusiasm, and Attenborough portrayed him as a Santa Claus bringing kids presents — some of which want to eat their recipients. The following year, Attenborough was Kris Kringle in John Hughes’ remake of Miracle on 34th Street.

(READ: Richard Corliss on Attenborough in Spielberg’s Jurassic Park)

Cheerful beneficence may have been a family legacy: Mary Clegg Attenborough helped found the Marriage Guidance Council (now known as Relate), which dispensed sexual advice to those otherwise afraid of seeking it. Her husband Frederick was a don at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where Richard was born on Aug. 29, 1923. His youngest brother, John, who died in 2012, became an executive at Alfa Romeo; the middle brother is David Attenborough, the polymath host-producer of BBC science series. Richard and David shared an infectious intellectual enthusiasm and the gift for clarifying, perhaps simplifying, big ideas. But Richard was no scholar. He entered the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (for which he would eventually serve as president) and, after joining the Royal Air Force, was assigned to its film unit, having suffered permanent ear damage during test flights.

The curious and salutary aspect of Attenborough’s distinguished acting career, during World War II and for several decades afterward, is that he often played flawed, shady or malevolent characters. He was the cowardly sailor in his 1942 film debut, in Noël Coward and David Lean’s In Which We Serve, and the submarine seaman driven close to madness by claustrophobia in Morning Departure (1950). He used a British gunboat to smuggle wine and armaments in The Ship That Died of Shame (1955) and played an electronics expert who sold secrets to the Soviets in The League of Gentlemen (1960). The Attenborough smile may have crinkled into St. Nick benevolence in his 70s, but early on it was the chummy rictus of a man intent on taking your watch, your wife or your life.

His most notorious and revered early role was as Pinkie Brown, the 17-year-old crime boss in Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock — first on the West End stage in 1944, when Attenborough was 20, and then in John and Roy Boulting’s film version three years later. Running a small gang in seaside Brighton, Pinkie shoves one man to his death from a haunted-house ride, pushes another off an upstairs landing in his rooming house and scars the face of a third with the straight razor he loves to fondle. Pinkie gets his own cheek slashed by the rival Colleoni gang — sounds like Corleone — and marries the innocent waitress Rose (Carol Marsh) just to keep her quiet or kill her. At her request he makes a recording to memorialize their affair. As Rose gazes lovingly through the booth window, he says, “What you want me to say is I love you. Here’s the truth: I hate ya, ya little slut. Ya make me sick.” When the law closes in, Pinkie nearly persuades the girl to take her own life in what he calls “a suicide pax. That’s Latin for peace.”

Turning his smooth, boyish face into a soulless mask and toying with a cat’s cradle of string like a killer’s rosary, suitable for strangling, Attenborough made Pinkie an indelible villain: the mobster as monster. “In those days,” he later recalled, “the character of Pinkie was a macabre novelty in British films. It was hard to understand how somebody like that would feel as he razor-slashed you, or as he told a girl to put a gun in her mouth to shoot herself. That is the kind of enormity I had to convey.” He did it brilliantly, without shouting invective or italicizing his evil. His glassy glance was a Medusa stare, its own mortal weapon.

Brighton Rock (named for a hard candy sold at the resort) was one of six films, in a wide range of tones, that Attenborough made for the Boulting twins. In the first, 1945’s Journey Together, he played an RAF cadet who must forsake his dream of piloting to become a navigator. In 1948’s The Guinea Pig (known as The Outsider in the U.S.), the 25-year-old convincingly played a 13-year-old working-class boy brought into a posh school as part of a social experiment. Later Boulting brothers films cast Attenborough playing his more familiar shifty persona, with harried upper-class twit Ian Carmichael as his comic foil. In Private Potter (1956) his character steals artworks captured by the Germans to sell them on the black market. In Brothers in Law (1958) he played a worldly-wise barrister with an eye for the ladies. And in the corrosive satire I’m All Right Jack (1959), he played a scurvy businessman who wants to peddle missiles to the Arabs.

By his 40s, Attenborough was a respected character actor with an adventurous taste in roles. He was the martinet who bends his own rules to save his men in Guns at Batasi (1964). He was a henpecked husband, either standing by his domineering wife (in 1964’s Séance on a Wet Afternoon) or murdering her (in 1962’s The Dock Brief, called Trial and Error in the U.S.). He was the practiced philanderer in the witty social comedies Only Two Can Play (1962) and A Severed Head (1971) and, most boldly, the serial killer John Christie — mousy of demeanor, ruthless of intent and execution — in 10 Rillington Place (1971). His Christie makes a perfect cinematic brother to the slick and just as sick Pinkie Brown.

But British films couldn’t contain Attenborough’s ambition. He broke into Hollywood with 1963’s The Great Escape — he was Bartlett, the brains of the operation that sprang Steve McQueen, James Garner and the rest from a Nazi stalag — and parlayed that blockbuster into important roles as World War II officers opposite James Stewart in The Flight of the Phoenix (1965) and McQueen again in The Sand Pebbles (1966). And then, having achieved international renown, he realized that what he really wanted to do was direct.

(READ: Richard Corliss’s tribute to James Garner)

His first film as director was his most audacious: Oh! What a Lovely War, an adaptation of Joan Littlewood’s bleak synoptic history of the Great War set to the songs soldiers sang as they marched to their mass deaths. The battlefield would be the focus or backdrop for many Attenborough films: World War I in Young Winston (a Churchill biopic) and In Love and War (Ernest Hemingway on the front lines), World War II in A Bridge Too Far and his last feature Closing the Ring. He documented the struggle for independence in India with Gandhi and South Africa with Cry Freedom — solidly liberal films of the furrowed middle brow that came to life with Attenborough’s inspired casting of the little-known Ben Kingsley as the Mahatma and the young Denzel Washington as Steve Biko.

Attenborough was carrying the epic torch brandished by David Lean, his first director, but without the spectacular visual acuity and understanding of obsessive personalities that elevated Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai and Lawrence of Arabia to greatness. Lean was the movie poet, Attenborough the conscientious craftsman. And when deprived of Important Issues like war and death, he often stumbled. His film of A Chorus Line (1985) captured none of the original musical’s urgency; his 1992 Chaplin, despite an impressive performance by Robert Downey Jr., was a bloated catalog of the silent clown’s misfortunes with young women. Only the 1993 Shadowlands, with Anthony Hopkins as writer C.S. Lewis and Debra Winger as the American poet he loves and tends through illness, found a pleasing balance of tone and emotional texture, of heart and ache.

(READ: Richard Corliss on Debra Winger in Attenborough’s Shadowlands)

No question, the man’s life was blessed and lucky. The Queen made him a knight in 1976 and a baron in 1993, which earned him a seat in the House of Lords (Labour, of course). And in 1952, as part of the original West End cast of Agatha Christie’s The Mousetrap, he received a share of the profits of that play, still running in its 62nd year; he used what was left of that annuity to help finance Gandhi. But fate had some heartache in store. Attenborough’s eldest daughter, Jane, along with her daughter and mother-in-law, perished in the South Asian tsunami of Christmas 2004. Years later he said, “I can talk to people about Jane now, although sometimes I can’t get the words out. I can also see her. I can feel her touch. I can hear her coming into a room.”

Attenborough’s co-star in both The Mousetrap and The Guinea Pig was Sheila Sim, his wife since 1945. In 2012, after being diagnosed with senile dementia, she took residence in Denville Hall, the actors’ home that she and her husband had helped establish. Attenborough, who had outlived a stroke and coma in recent years but was severely incapacitated, moved into Denville Hall with his bride of 69 years.

Sim, now 92, survives Attenborough in the shadowlands. As for Lord Dickie, he may be charming a whole new stratum of celebrities. We imagine him rounding up a celestial cast for some new superproduction — but only if they want to. “Entirely up to you, darlings.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com