FERGUSON, Mo. — The death of 18-year-old Michael Brown is above all a tragedy for his family. But in Ferguson, Mo., there is more than enough tragedy to go around. Virtually no one connected to the tumult in this St. Louis suburb—whether by proximity, profession, or ideology; by happenstance or choice—has escaped the nightly clashes without suffering in ways big or small.

When darkness falls, violence rips through a battered strip of downtown and forks into quiet neighborhoods. Families are trapped in their homes as gunshots ring out and cops fire tear gas into apartment complexes. It’s become enough that some people are ready to leave. Anita Matlock, a 20-year-old certified nurse assistant, is breaking her lease at Canfield Green, the beige-and-brown three-story apartment complex that fronts the street where Brown was shot. The early morning hours there are now pierced by volleys of gunfire. “It’s too disruptive,” says her mother, Yvonne Matlock. “She can’t get in. Can’t get out. Can’t sleep.”

Ron Henry, from the nearby town of Florissant, says his fiancée Clarissa and his 3-year-old son, Ron Jr., had automatic weapons pointed at them by police while trying to leave his grandmother’s apartment near the center of the conflict. Their car was swallowed by smoke. “Rioting,” Henry says, “is the voice of the unheard.” But that doesn’t mean he wants to raise his family among it. “Does my three-year old son need to get gassed?” he asked.

The tumult has closed local schools, sending working parents scrambling to make arrangements to watch and feed their children. Last year, 68% of students in the Ferguson-Florissant school district received meal assistance of some kind; this year the program was extended to everyone. The loss of the subsidy stings for residents of a city whose median household income is about $36,000.

It’s been no better for businesses. Stores along West Florissant Avenue, the Ferguson thoroughfare that has been the locus of the riots, have been torched and looted. Many others in town are boarded up; the owner of a fashion boutique spray-painted “OPEN! BLACK OWNERS” onto the wooden planks covering the shop to deter vandals. At the shopping center about a quarter-mile down the road—where Missouri National Guard tanks are arrayed in rows in the parking lot and military observers perch on rooftops— sales have plunged as stores close early to avoid the evening chaos.

For everyone in the area, unpredictable police roadblocks turn driving after dark into a maze without an exit. After midnight, residents can find themselves on the wrong side of police barricades, unable to get home or to work. Even on the most peaceful days since the shooting, the streets are still unruly and chaotic, a cacophony of honking horns, angry shouts and carloads of people hanging out of windows, slinging epithets at police.

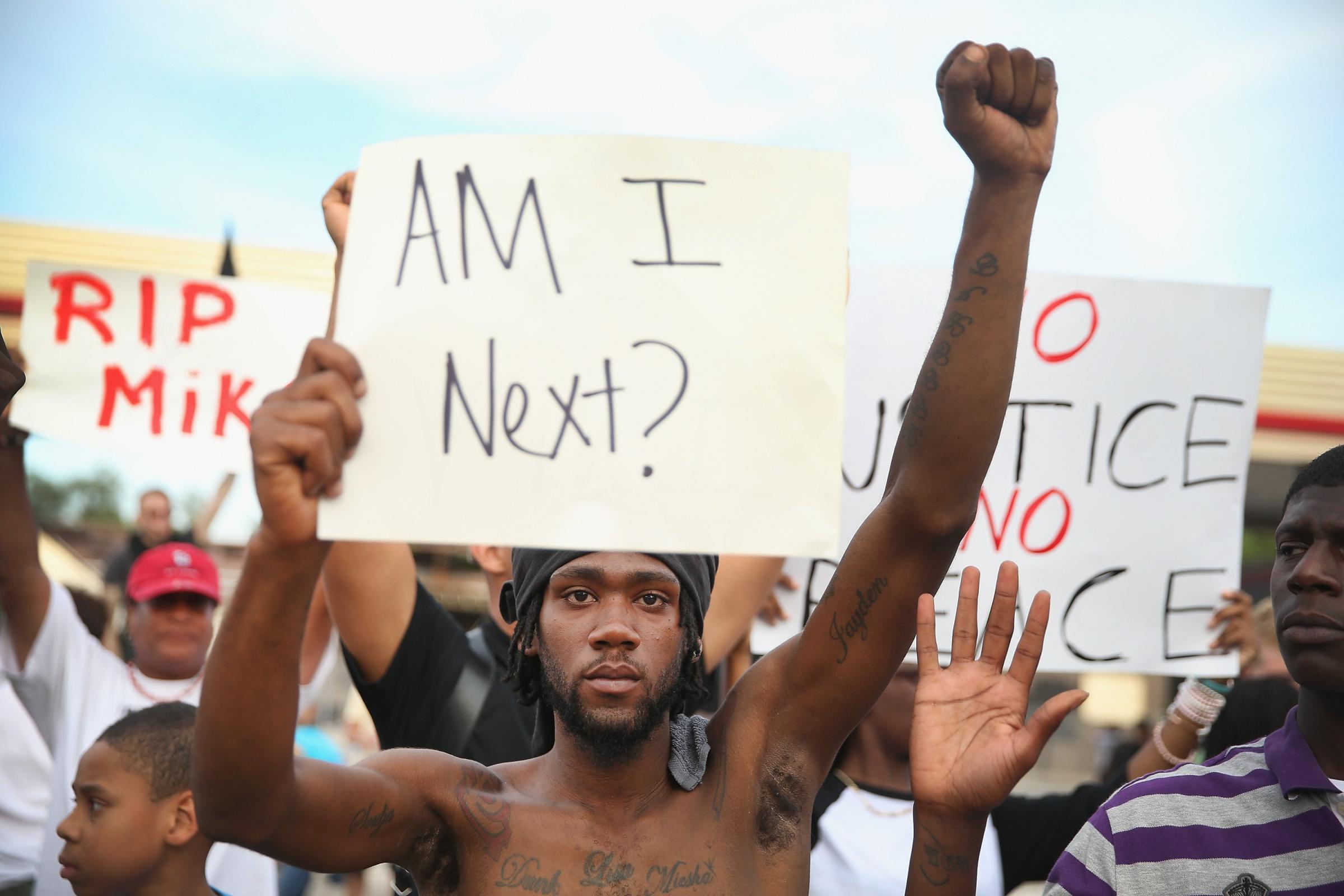

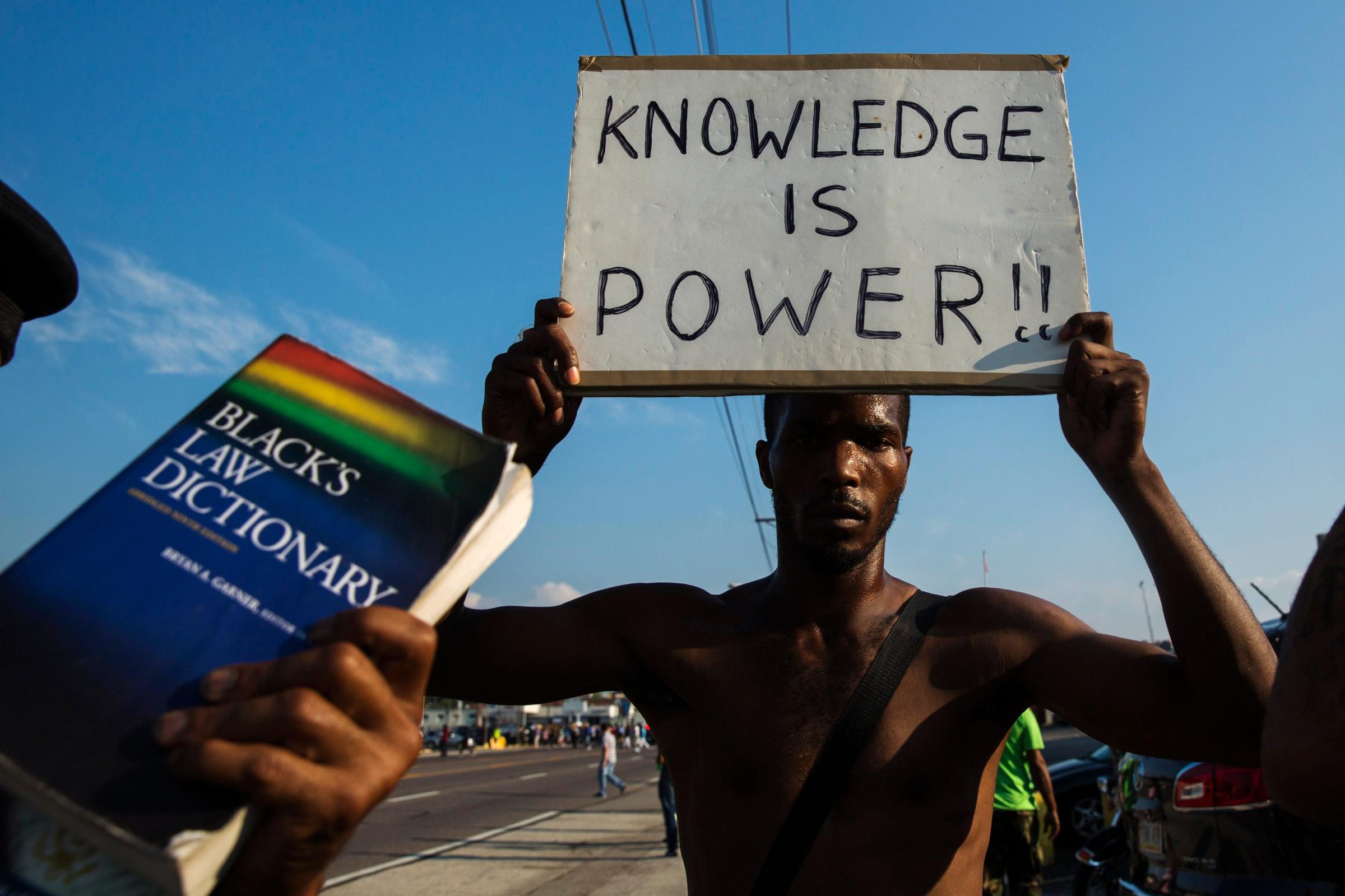

The vast majority of the hundreds, sometimes thousands of people protesting each day are law-abiding. But the large community of peaceful protesters, who have thronged the streets for nine days in an effort to bring social change, have seen a heartfelt cause partially co-opted by a small band of what law enforcement officials have described as “agitators.” In the morning, the protesters show up early to sweep the streets of the previous night’s trash. Day and night, they tote signs and chant slogans. On Monday, to comply with a new police edict that prohibited crowds from congregating in one spot, they resorted to walking laps, looping up and down West Florissant for hours, carrying red roses handed out by volunteers and passing out free water when people flagged in the stifling August heat.

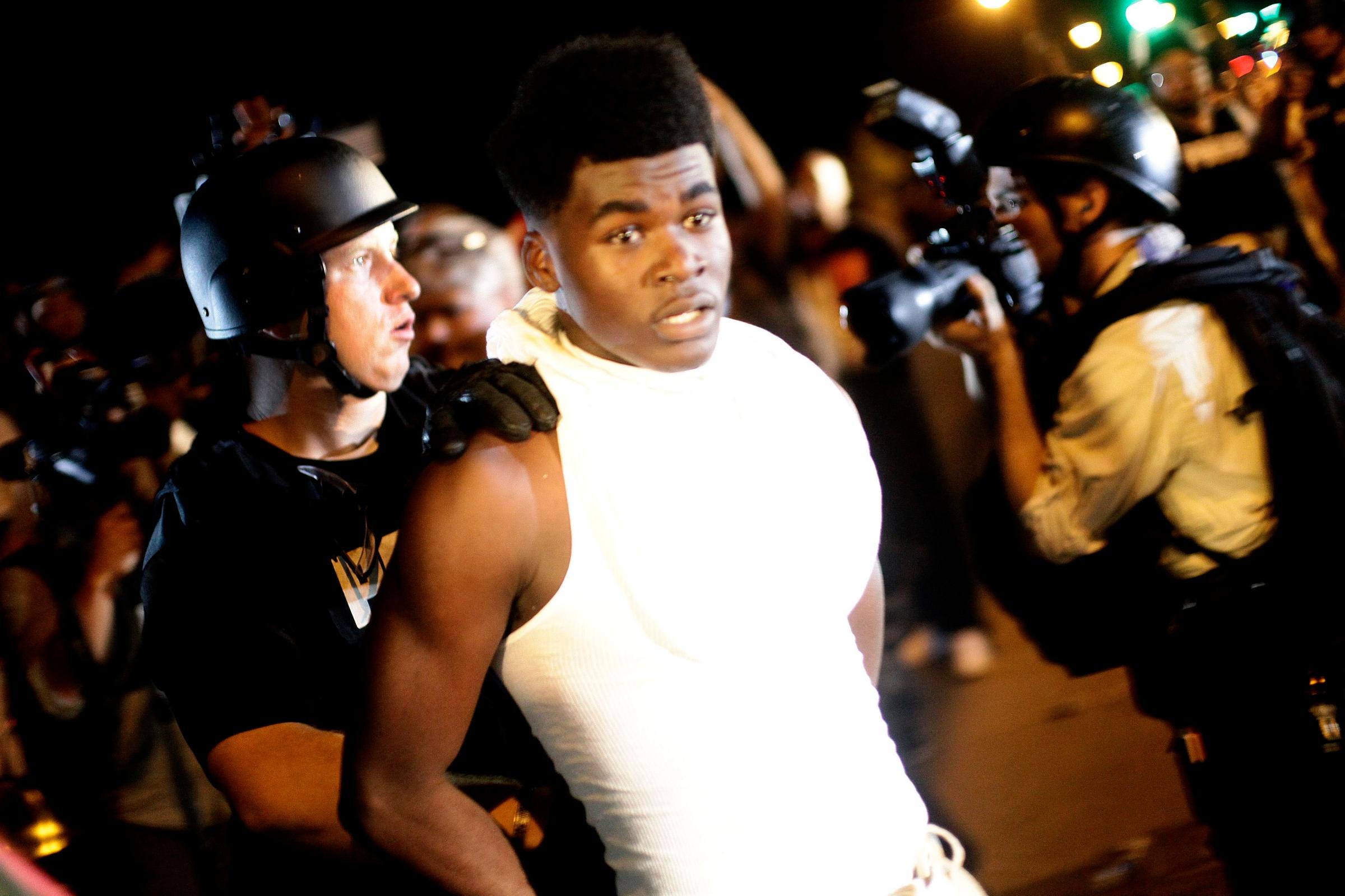

For much of the day, community leaders are able to steer protests into sanctioned areas and keep the crowd in check. The challenge comes after nightfall. That’s when a faction of agitators files into the streets. They are there not to protest but to fight. They can mingle with the protesters, cloaking themselves in the crowd and making it hard for police to distinguish the troublemakers from the rest. Many are not from Ferguson. At least 78 people were arrested Monday night, and while most were reportedly from Missouri, some were from places as far-flung as California, New York, and Washington D.C.

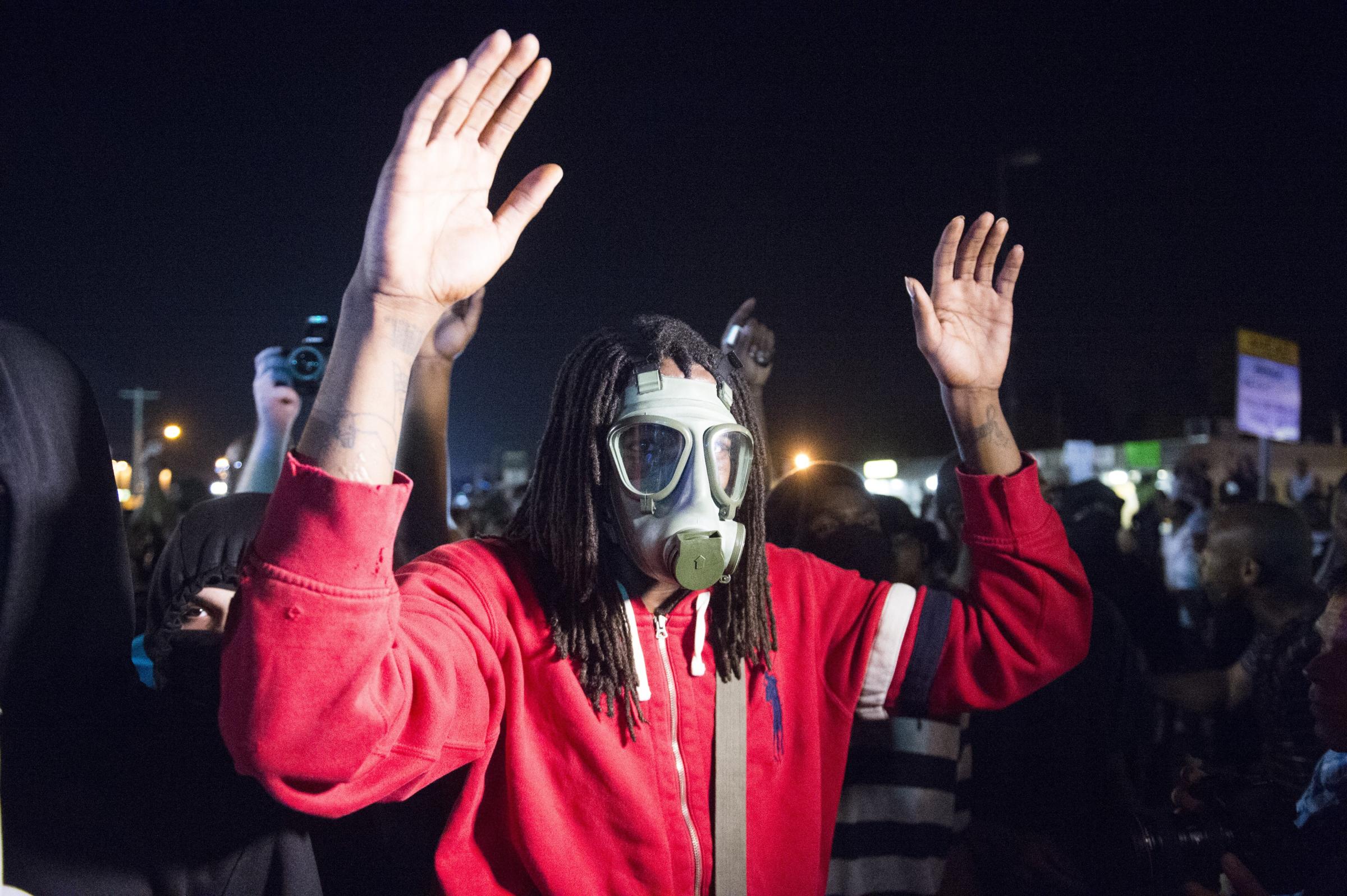

According to locals and local enforcement officials, the ranks also include multiple gang members from Chicago and East St. Louis who have forged an uneasy truce to pursue a common enemy. There are young gang members who wrap red bandannas over their mouths, gas mask-wearing anarchists, and communist revolutionaries.

The violent faction has repeatedly derailed the demonstrations, despite the efforts of peaceful members of the crowd. Each night the struggle starts again. On Friday, the peace held until the early morning hours, when the fighters began looting businesses, hurling Molotov cocktails and setting fires. On Saturday, as time ticked away toward a midnight curfew, the peacekeepers roamed the crowd, imploring people to go home. Those that stayed were bent on conflict. “We ready to die,” one shouted as the gas came out. “They armed. We armed. Let’s do this!” said another.

Monday night brought an eerie calm to the streets. It was shattered around 9:30 p.m., when a clutch of agitators surged toward a police line, hurling glass bottles and plastic containers of water at officers. Police gathered their riot gear and put on their gas masks, readying for battle. Community leaders pleaded for the cops to hold off and confronted the provocateurs, linking their arms to form a human barricade between the crowd and the police. “Why are you doing this to us?” one peacekeeper screamed. It was a remarkable scene that seemed to defuse the situation.

A few minutes later someone threw a bottle, and the ritual chaos was unleashed.

As difficult as it is for the peaceful protesters, the skirmishes are no easier for police. Flat-screens around the U.S. have been flooded with images of armored trucks, riot-gear-clad police toting rifles, and clouds of gas. But those images rarely capture the chaos that precedes it.

Surveilling the streets of Ferguson is a chaotic job, marred by the mismanagement of the city police, jurisdictional tangles, hostile crowds, and tactics that seem to change nightly. The cops have been thrust into the impossible position of trying to balance intense political scrutiny with their mandate for public safety—and they are forced to carry out under the klieg lights of the national media, amid chaotic street fights.

“The situation, as volatile as it is, it doesn’t make a difference what decision you make. It will be wrong,” says one St. Louis County officer, who was not authorized to provide his name, as he patrolled a darkened street on Monday night, past graffiti scrawled on cement blocks that read “NO MORE PIGS.”

After heavy criticism for the military-style response by local law enforcement, the Missouri State Highway Patrol took control of the scene Thursday and adopted a laissez-faire approach. Riots broke out the next night. Police did little to stop the looting—partly on the advice of community leaders, who believed interceding could result in more violence. The next day, many protesters said they believed the hands-off treatment that allowed the rioting was a set-up to sully the crowd’s image.

The police are “working valiantly to protect the public, while at the some time preserving citizens’ rights to express their anger peacefully,” said Missouri Governor Jay Nixon, a Democrat. “As we’ve seen over the past week, it is not an easy balance to strike. And it becomes much more difficult in the dark of night, when organized and increasingly violent instigators take to the streets intent on creating chaos.”

The protests are fueled by a deep distrust between the community and the cops. It is hard to find a black man or woman at the nightly gatherings who does not have a story about experiencing some manner of racial profiling, intimidation and even brutality at the hands of police. “Black people want retribution,” says James Davis, 45.

The police—most of whom had absolutely nothing to do with Michael Brown’s death—have their own loyalties and grievances. “We’re all gangs,” says one police officer of the factions in Ferguson. “We’re in a gang too, just because of the uniform we wear.”

Meanwhile, the residents of Ferguson, weary of the nightly battles, are starting to worry what it will all yield. “It would be an injustice in his name to go back to the violence,” says Lacy Raye of St. Louis. “We just have to turn it into a positive. I think this will change everything, if we can put it in a positive light. But I don’t know.”

Witness Tension Between Police and Protestors in Ferguson, Mo.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com