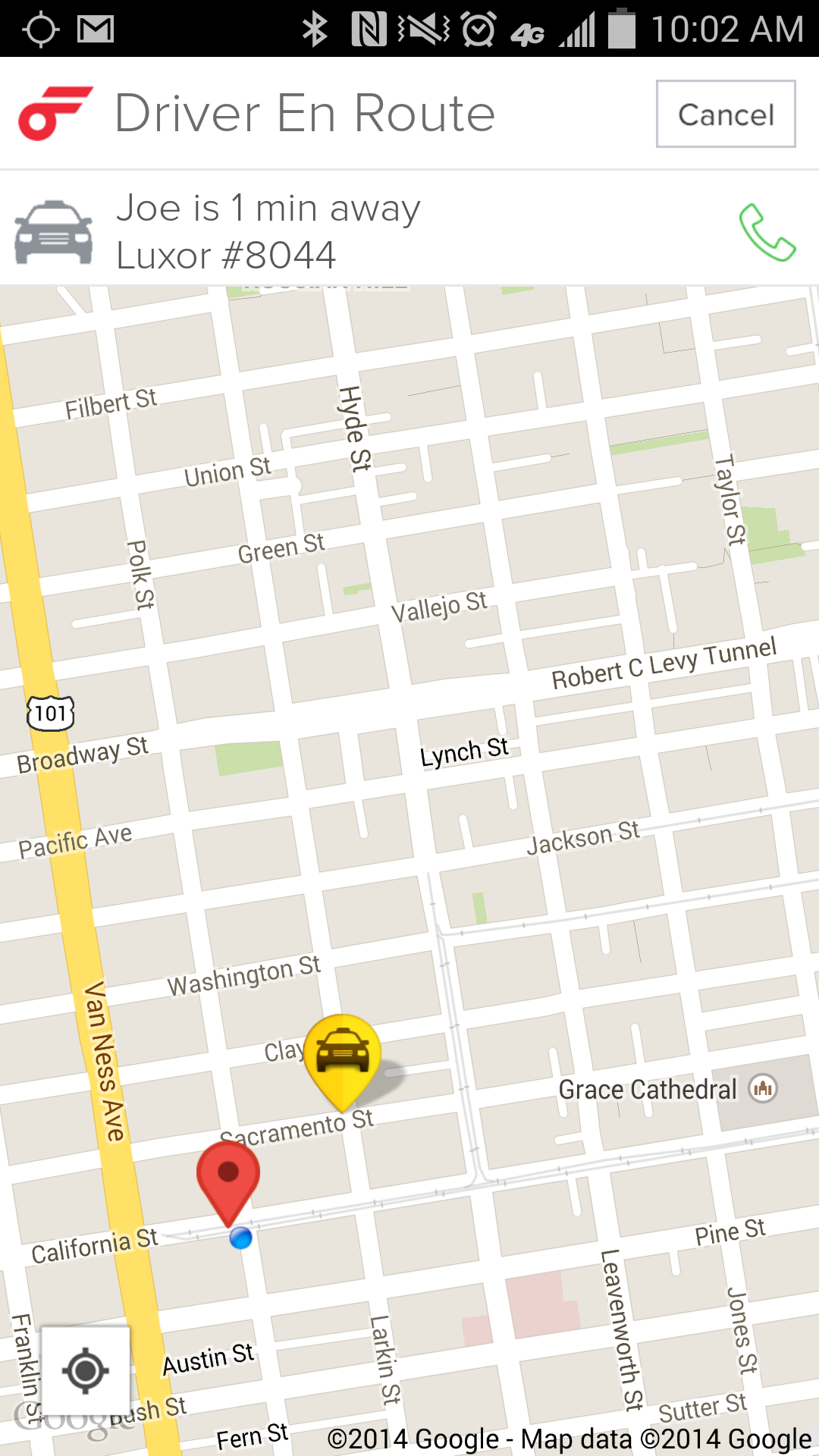

Standing on the corner of California and Polk in San Francisco, I took out my phone and ordered a ride from Flywheel, an app that’s competing with rival transportation services like Uber and Lyft by leveraging the thousands of taxis already on the road. Like with those services, once I order a Flywheel ride, a map pops up with a car icon, showing me where my ride is in relation to me and allowing me to monitor the driver as he or she gets closer.

Or at least that’s how it’s supposed to work.

On this particular morning, as I watched multiple Lyfts go by (unmissable with their trademark giant pink mustaches attached to the cars’ grilles), and a couple Ubers (the black cars now identifiable by small logos that must be placed on their windows), my driver’s icon drifted away from me. After some minutes passed, I called the driver, who assured me he was on his way. When he continued to travel not towards me, I canceled the order and got a new Flywheel, which picked me up and promptly delivered me to the company’s San Francisco office, with my bill and a 20% tip paid automatically through the credit card I stored on the app.

Once at Flywheel, Chief Product Officer Sachin Kansal explained what had likely happened with my misguided driver. “He may have been ride-stacking,” Kansal explained, meaning that the driver accepted my order on the app and then took a street hail, thinking he could deliver the latter before I ever knew the difference. But the moment I canceled my ride, the driver’s plan was foiled. He would be blocked from the system until Flywheel investigated the case, and these did not appear to be circumstances that would yield quick forgiveness from administrators. Kansal made sure I knew how swiftly justice would be dealt, because this is not the kind of mistake companies can afford to treat lightly in the midst of the Great Ride App Wars.

San Francisco has been transformed into a city full of smartphone-wielding guinea pigs, willing beta testers who try out new services and shovel feedback to engineers. But while many transportation startups are busy dreaming up new and unfamiliar offerings, Flywheel and similar companies like Curb and Hailo are trying to breathe high-tech life into the old taxis that have been around for decades. That business model comes with limitations as well as certain advantages—the biggest of which may be that the city of San Francisco is proving a willing ally, and that could in turn prove a model for other metros. (Lyft did not respond to an interview request for this article, and Uber declined.)

San Francisco’s Municipal Transportation Agency’s “position is that there is a public good to having a regulated taxi industry,” city spokesperson Kristen Holland said in an email. “We want to encourage the public to take San Francisco taxicabs by making them aware of the e-hail option and letting them know the benefits of taking a San Francisco taxicab.”

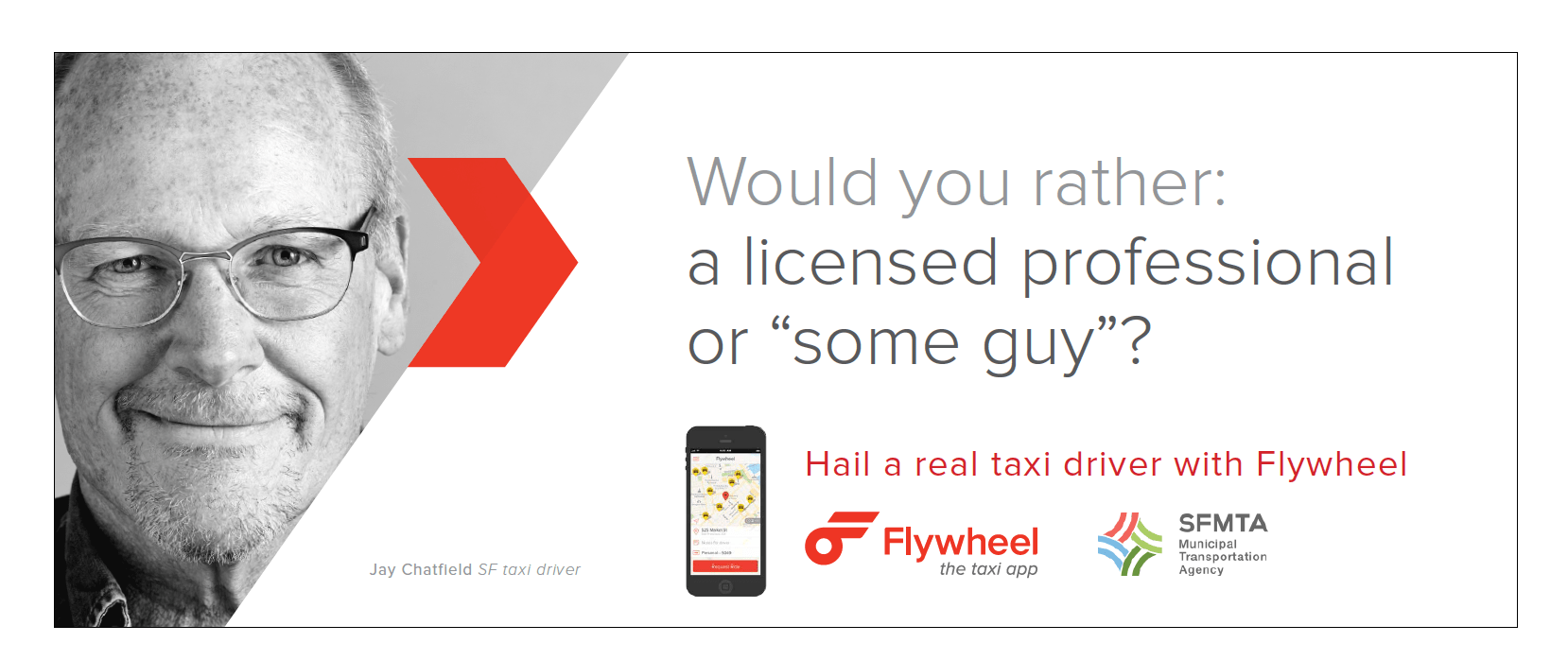

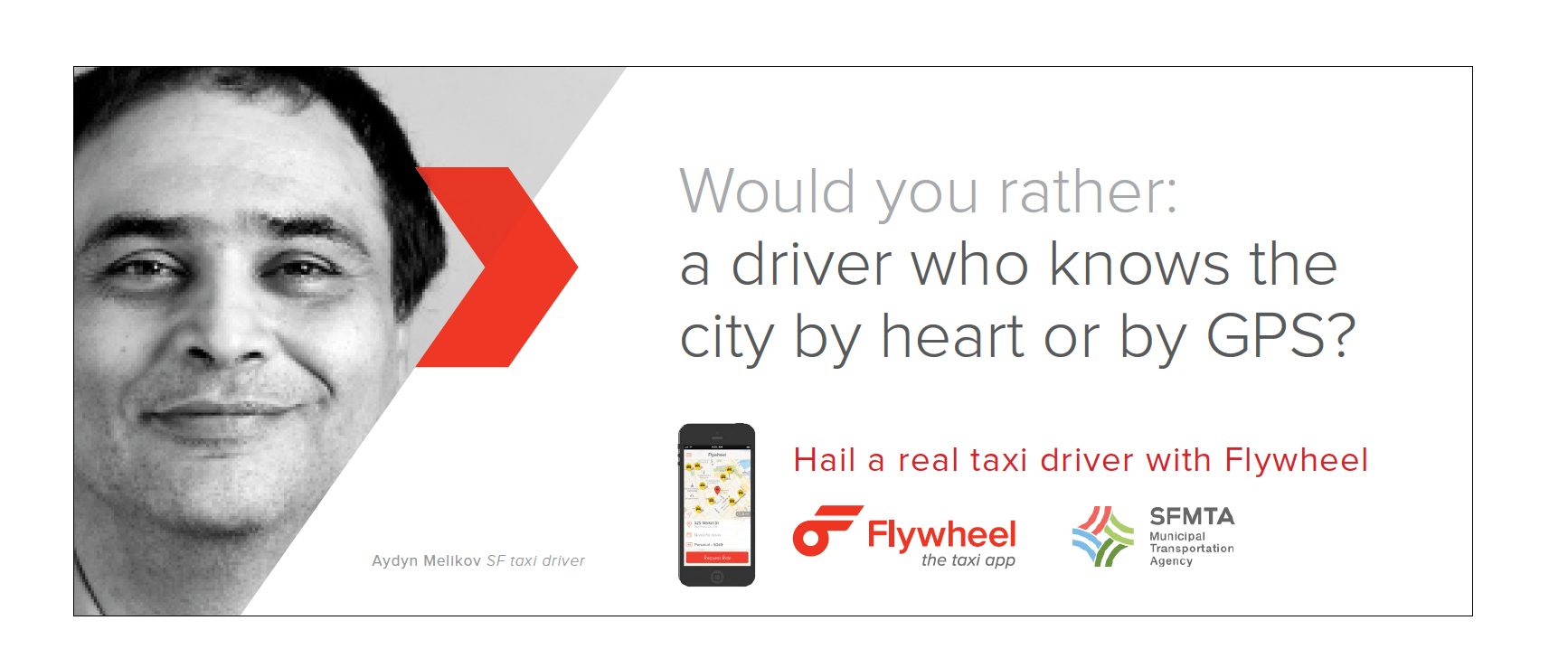

Earlier this summer, the city and Flywheel teamed up to get their pro-taxi message across by putting cheeky ads like this on the sides of city buses:

And this:

By getting its app adopted a whole fleet at a time, Flywheel now has its system in 80% of San Francisco’s approximately 1,800 cabs and is aiming for 100%. Both the city and companies like Flywheel have a financial interest in cabs doing well—Flywheel through the 10% cut it takes off the base fare and the city through its medallion system, which will yield an anticipated $10 million in fiscal year 2015. Holland says that the city also supports cabs because they’re a known quantity. The city regulates them and decides exactly how the drivers are trained. Questions about insurance and liability, which have plagued startups innovating new transportation systems, have long been answered when it comes to cabs.

Taxi drivers, many bitter that they have to deal with more onerous regulations than drivers for companies like Lyft, have taken to writing down license plate numbers of cars with pink mustaches and reporting them to insurance companies. While cabs are clearly commercial vehicles, Lyft drivers are often using their personal cars to make money, and some insurers have canceled Lyft drivers’ policies after finding out they had only forked out for non-commercial plans.

Using apps like Flywheel is a way for taxis to fight fire with fire instead of tattling, however justified it might seem. Flywheel’s Kansal says that drivers may double the amount of rides they get in a shift through the efficiency that the system provides, matching people who need rides with nearby drivers. “There are weaknesses that others have. There are regulations that they may be breaking,” he says. “But 90% of our energy is spent on making sure this experience always stays top notch. That the experience that you had this morning never happens again.”

While Flywheel can’t turn cabs into fancy black cars or Lyft Plus SUVs, customers who order a taxi never have to worry about surge pricing, premiums that other companies charge in times of high demand. And while Flywheel can’t innovate at the speed of the other companies, given the limitations of what a fleet cab can be, it did just roll out service to airports in San Francisco, Seattle and L.A—something less established fleets still can’t legally do in many cities due to long-standing airport regulations. The California commission regulating the new services like Uber and Lyft has threatened to shut them down if drivers keep showing up at arrival and departure areas without proper permits.

Kansal believes his company can outfit cabs in a way that allows them to disrupt the companies that disrupted cabs in the first place. The fleet model is “very scalable,” he says, though the app is now densely present only in San Francisco and available in just a handful of other cities, most on the West Coast. (Competitor Hailo is the leader among taxi apps on the East Coast and in Europe.)

But the equation isn’t so simple as making lists of pros and cons for new ride-providing companies and app-enabled taxis. After my interview with Kansal, I tried to hail a car through Curb, a rival app that just rebranded itself after previously operating as Taxi Magic. After failing to get a taxi assigned to me before five minutes passed by I went back to Flywheel. A taxi arrived, and I asked my driver Casey Callahan what he thought of using the platform.

“I have mixed feelings,” he says. “You get a lot of business you wouldn’t normally get, and it gives us an edge against Uber, but they take a kind of big cut.” Ten percent seemed too high to Callahan, and that’s the kind of resentment that can fester. UberX drivers protested angrily outside Uber’s HQ in San Francisco earlier this year when the company started taking a bigger cut of the fare, many drivers threatening to go work for someone else. Callahan said the Flywheel app can also have technical kinks, and it remains painful to pass up a willing street hail once he’s agreed to pick up a Flywheel customer, the temptation to which my driver succumbed.

Callahan described all the driver-luring and price-cutting companies are doing to one-up each other in the Bay Area as “cutthroat capitalism at it worst.” But he said that if cab drivers don’t use technology and whatever else they can to fight back, they’re going to go the way of the dodo and the stagecoach. “This is going to be one more thing that’s gone from the American way of life,” he says.

He says he chose driving for a cab company over the new services partly because he doesn’t own his own car and feels that buying one through a company, as some Lyft Plus drivers do, is the equivalent of being an “indentured servant.” Myriad factors could send a driver one way or the other. Long-time cabbies know how much they can make in a shift, while newer companies continue to play with prices and what cuts they take. There’s also the ethos of the job, like Lyft’s requirement that a driver fist-bump each passenger, while a cool distance in taxis is the norm and Uber black car drivers will open your door. There are hours, incentives, pride, rules about where certain companies can go and who they can pick up. And so on.

For those championing taxis, the question is whether cab drivers who long roamed without competition, facing no penalty if they ditched one fare for another, can give their industry the kind of customer-service makeover it takes to convince a San Franciscan to order a Flywheel instead of something from the long menu of other options.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com