Correction appended, Aug. 20

Oct. 14, 1981: Robin Williams’ first time with Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. He begins by denying he’s nervous and proves it by slouching as if he were a deflated balloon. “I suffer from severe dyslexia too,” he tells Carson. “I was the only child on my block on Halloween to go, ‘Trick or trout.'” Instantly he transforms into his adult neighbors: “Here comes that young Williams boy again. Better get some fish.” Trying to unearth some backstory, Carson asks, “Where is home for you?” Then, thinking better, “Or did you come from a home?”

That cues Robin as a visitor to an asylum talking to a patient: “If you haven’t taken your medication yet, it’s gonna be fun.” Then, as he mimes struggling in a straitjacket, he channels a concerned doctor: “How are you, Mr. Williams?” Noticing the overhead mike, he rises, shouts, “Look! Flipper!” and makes a dolphin cry. “Right now there’s a soundman going, ‘What are you doing?'” and he outfits himself with imaginary headphones. Trying to calm himself, he says, “Relax, relax, relax, you’re on TV” and, to Carson, “You’re a nice man, you won’t hurt me.” Reaching for the host’s famous coffee mug, he takes a sip, saying, “Don’t be afraid, the sores went away.” And in his macho voice: “A real man can stand up to herpes!”

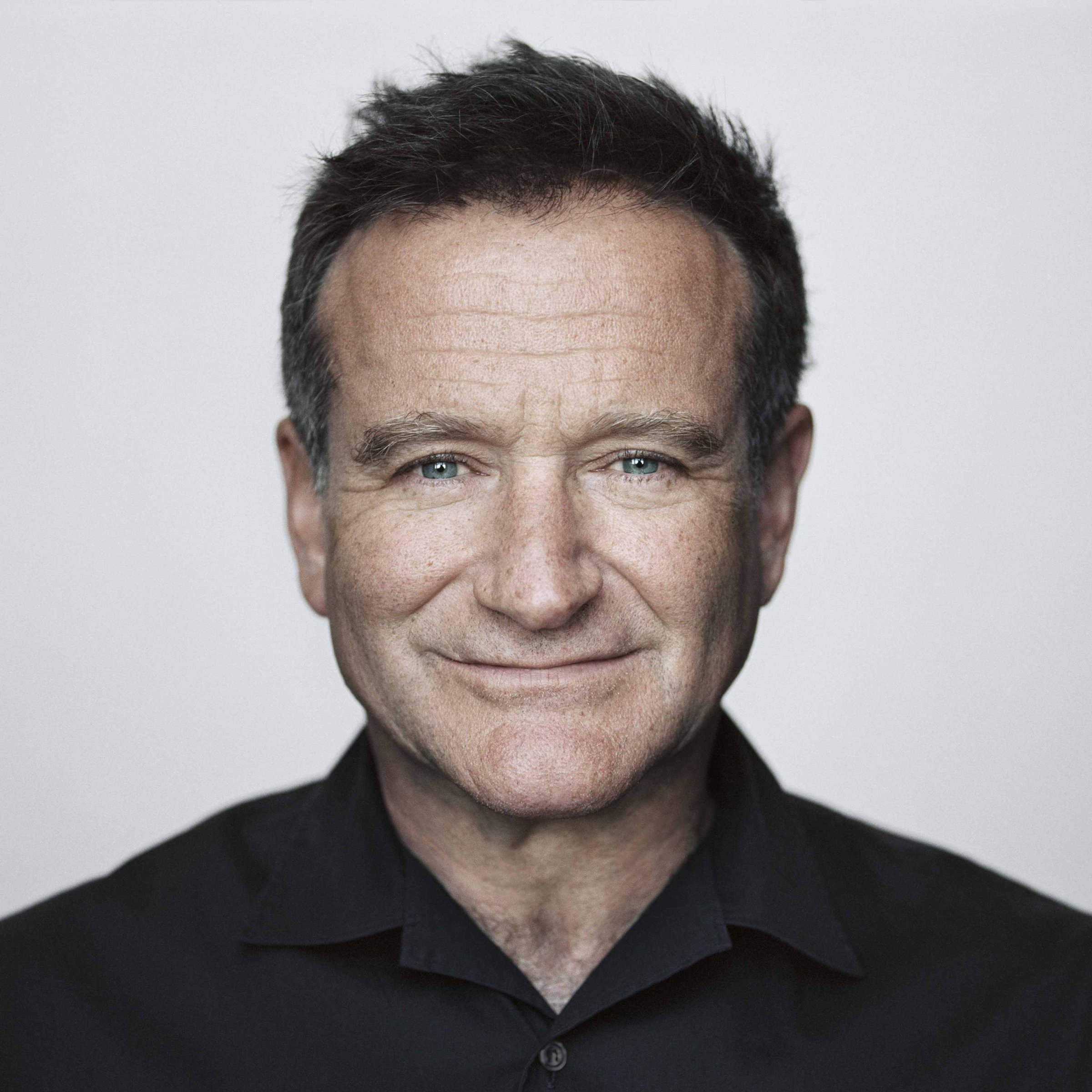

In this first 75 seconds of his debut with the reigning king of talk TV, Williams slipped into and out of a half-dozen characters, as if his mind were a Whac-a-Mole game housing a million critters of all species and shades, each ready to pop up unbidden. He was already a TV sensation as the benign extraterrestrial Mork from Ork on Mork & Mindy and had starred as a comic-strip sailor in Popeye. But that Tonight Show stint revealed the distilled form of Williams’ unique genius–we can use the phrase without fear of exaggeration–in stand-up comedy and his visits with Carson, Dick Cavett, David Letterman, Jay Leno and the other late-night lions.

For all his serious film roles, which garnered him a Supporting Actor Oscar (for Good Will Hunting) and three Best Actor nominations, Williams at his purest was the id unleashed, geysering nonstop shtick of the highest order. “You’re only given one little spark of madness,” he said. “If you lose that, you’re nothin’.” His spark was a forest fire, a comic conflagration that warmed the world and damaged no one.

Perhaps excepting himself. Addicted to cocaine and alcohol, Williams also made frequent guest appearances at rehab clinics, held over by his own demand. His wild ways exhausted two wives and widowed the third, Susan Schneider, whom by all accounts he adored. He suffered from depression, not a rare malady for comedians, and surrendered to it on Aug. 11, when he hanged himself in his Tiburon, Calif., home. Rigor mortis had already set in when his personal assistant found him. Williams was 63.

His death touched a collective nerve, and the hearts of his myriad fans. Some looked back with awe at the nonpareil comedy he pinwheeled, playing indelible cartoon characters in Aladdin, Robots and Happy Feet. But many more mourners thought of Williams as one of the brave little men he incarnated in dramatic films. Moviegoers detected the ache in his comic panache and the sad sweetness at his core. They loved the guy. Didn’t he know that? And couldn’t that realization give him a life-preserving satisfaction?

The most poignant tribute came from his daughter Zelda, 25. “My family has always been private about our time spent together,” she said in a statement. “It was our way of keeping one thing that was ours, with a man we shared with an entire world. But now that’s gone, and I feel stripped bare. My last day with him was his birthday”–July 21, three weeks before his death–“and I will be forever grateful that my brothers and I got to spend that time alone with him, sharing gifts and laughter. He was always warm, even in his darkest moments. While I’ll never, ever understand how he could be loved so deeply and not find it in his heart to stay, there’s minor comfort in knowing our grief and loss, in some small way, is shared with millions.”

The urge for Robin McLaurin Williams to share his gift may have stemmed from neglect in his early years. His father Robert, a Ford Motor executive, moved the family from Chicago, where Robin was born, to Detroit. Robert died in 1987. (In Robin’s 1998 Oscar acceptance speech, he reserved the final thank-you for “my father up there, the man who when I said I wanted to be an actor, he said, ‘Wonderful, just have a backup profession, like welding.'”) Robin’s mother Laurie, a former model, completed the image of a picture-book Wasp family. “He also had a really formal upbringing,” Joan Rivers, who relied on Williams as an inspired TV-chat companion, tells Time. “He came from an upper-middle-class family, very educated, very well read, very knowledgeable about everything, about literature.”

With both parents often absent, Robin was a lonely child, playing with his enormous collection of toys; the family maids were his main minders and first audience. The Williamses later moved to a 40-room home in Bloomfield Hills, a suburb of Detroit, and when Robert retired he settled the family in Marin County, California, where Robin attended Redwood High School and emerged from his shell of shyness to join the drama society. In senior year he was voted both “funniest” and “least likely to succeed.” He attended Claremont Men’s College (now Claremont McKenna College) and later received a scholarship to study at New York City’s Juilliard School. One of his classmates was Christopher Reeve, who would find stardom as the movies’ Superman in 1978, the year Williams broke out as Mork–two actors with Broadway dreams who reached megafame playing endearing aliens.

An Eruption of Improvisation

Williams had the makings of a fine dramatic actor: a friendly face and a sturdy frame, with a mime’s agility and a powerful voice–from the chest, not the throat–that echoed not Brando and the Method men but the English and American classicists. Yet John Houseman, the eminent film and theater producer who served as Juilliard’s drama director before becoming a TV star on The Paper Chase, told Williams he was wasting his time as a student. Playing one character at a time, for months on end, didn’t properly exploit Williams’ glossolaliac gift of being everyone at once; that capering intelligence could find its full expression in stand-up comedy.

Most comics, then and now, honed their routines to letter-perfection. A few courted inspiration, and risked failure, with solo improv comedy. Mad-professor types like Brother Theodore and Irwin Corey turned their performances into rant-lectures that disdained punch lines and spiraled into twisted logic. Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor were hipster social critics following their own elevated radar. Jonathan Winters, a Carson favorite (as dear Maude Frickert), was closest to Williams: he pirouetted from character to character, emitting more weird noises than a Warner Bros. cartoon soundtrack. The true brethren of these brilliant misfits were not stand-up comics but the most adventurous jazzmen. And if Bruce was the Louis Armstrong of solo improv comedy, and Winters the Charlie Parker, then Williams was Sun Ra, the farther-than-far-out composer who claimed he came from Saturn.

Of course Williams had a notion of what he would say onstage and often played unannounced gigs at comedy clubs to hone his material. But the safety net of even a discursive narrative was too confining for all the voices waiting inside to burst out, like Linda Blair’s devils in The Exorcist, but hilarious. Williams took the anarcho-improv impulse and flew with it–a Robin reaching the surreal stratosphere. When everyone else was analog, he was digital. That’s why his comedy had many admirers but virtually no imitators. Who else could even think of doing that?

Moving to Hollywood, Williams served briefly in an ill-fated second edition of the TV vaudeville show Laugh-In. Then Garry Marshall, producer of Happy Days, saw Williams’ otherworldly appeal and tried harnessing it by casting him as Mork. In a 1993 Today interview with Gene Shalit, Williams mimicked Marshall’s gruff Bronx bonhomie in hiring him: “It’s not Shakespeare, you’ll have a good time.”

In February 1978, Williams’ Mork, beamed down from the planet Ork to join the Fonz (Henry Winkler) and Richie Cunningham (Ron Howard) in 1950s Milwaukee, proved such a sensation that the nanu-nanu boy got his own sitcom spin-off seven months later and graced the cover of Time the following year. The Mork & Mindy situation was familiar–sort of a heterosexual My Favorite Martian, with Mork finding a romantic partner (Pam Dawber’s Mindy) in Boulder, Colo.–yet the show changed TV comedy, a little, by occasionally letting the star run improvisationally amok. In the fourth season, he brought Winters into the show as Mork and Mindy’s child Mearth. (Orkans age backward, if you’re wondering.) Now Winters and Williams could do their thing together–the meeting, on prime-time TV, of two wonderfully warped minds.

Tenderness on the Big Screen

He may have left Juilliard, but Juilliard stayed with him. Instead of pursuing a career in movie comedy, as Pryor and the first stars of Saturday Night Live did, Williams parlayed his fame as Mork and Popeye into securing serious roles. Why does a clown want to play Hamlet? Maybe because he thinks he is that melancholy soul whom others find amusingly odd. (Williams and another unique stand-up comic, Steve Martin, played not Shakespeare but Beckett in Mike Nichols’ 1988 Lincoln Center production of Waiting for Godot.)

Whatever the compulsion, Williams took the lead as the suburban dad facing Job-like calamities in The World According to Garp. He was the Russian immigrant in Moscow on the Hudson, the psychologist with catatonic patients in Awakenings, the dead man searching for his wife in What Dreams May Come. He earned three Best Actor Oscar nominations–as the DJ in Good Morning, Vietnam, the sainted teacher in Dead Poets Society and a homeless man in The Fisher King–all for roles that allowed him to assume multiple voices, at least in passing. (In Dead Poets he persuades prep-school boys to love Shakespeare by imitating Brando in Julius Caesar and imagining John Wayne as Macbeth.) He even got himself cast in Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 film of Hamlet. Not the lead; Osric the courtier.

If his solo comedy work aimed to challenge and astound, most of his films tended to reassure, to touch the heart–sometimes with a brisk massage, as in the gay valentine The Birdcage, and at least once with egregious sentiment: the bullying tearjerker Patch Adams, which cast Williams as a clowning healer of sick children. (Apologies, reader, if that one got to you.) He was more comfortable in an outright comedy like Mrs. Doubtfire, where the sentiment of a divorced father scheming to be near his kids took second place to the spectacle of Robin as a bosomy Mary Poppins.

A Friend in Need

Williams’ restless energy found another outlet in donations and appearances for 28 charities, according to the monitoring website Look to the Stars. He supported the St. Jude Children’s Hospital and exported laughter to soldiers in USO tours to a dozen countries. When comedy writer and performer Bob Zmuda founded Comic Relief USA, Williams signed on with Whoopi Goldberg and Billy Crystal to host a series of HBO specials that raised some $50 million for the homeless. Zmuda, citing Williams’ upper-middle-class background, tells People, “Robin always felt a little guilty about all the good things he was given, so he had a real place in his heart for people who were homeless and suffering. He and Whoopi and Billy not only did the show, they would go to shelters together and meet the people they were helping. They were the real thing.”

David Steinberg, the comedian who shared the stage with Williams in a 2013 concert tour, testifies to the star’s devotion to his mentor Winters, who died last year. “He would drive to Santa Barbara weekly,” Steinberg recalls, “to make sure Jonathan was O.K.–a comic genius looking after another comic genius. Robin looked after everyone. If only he would have looked after himself.”

He was a friend in need and deed to Reeve, who died in 2004 after being paralyzed from the neck down in a 1995 fall from a horse. Williams served on the board of the Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation, which raises money for research into spinal-cord injuries, and lifted Reeve’s spirits with his elfin humor. On the Today show, Reeve smiled as he spoke of one Williams visit: “Thank God I wear a seat belt in this chair, because I would have fallen out laughing. In the middle of a tragedy like this, in the middle of a depression, you can still experience genuine joy and laughter and love. And anyone who says life’s not worth living is totally wrong, totally wrong.”

Like the teachers he played in Dead Poets Society and Good Will Hunting, Williams was always available for consultation, especially among his colleagues in the brutal game of stand-up. When Jamie Kilstein, the comedian who co-hosts Citizen Radio on Sirius, admitted in an email exchange that he was “having a really hard time,” Williams phoned him for some late-night therapy. “A few months ago,” Kilstein says, “Robin called me to talk me out of my depression. He asked if it was a money issue, and I said no. He wanted to know if he could do anything. He told me not to stop. He said, ‘Just don’t.’ He just made me feel special.” The pity is that Williams, who made so many people feel special on the phone or in person or through the TV or movie screen, never found a Robin Williams to salve his psychic wounds.

His Final Act

Williams returned to series TV last year for The Crazy Ones, playing an adman running an agency with his daughter (Sarah Michelle Gellar). During a break in the shoot, says someone who worked with him, “Robin went and sat off to the side. And in that moment, his face just changed. He looked so exhausted and profoundly, deeply sad. And then one minute later, it was gone. He just snapped out of it and pulled himself back together. And you know what? He nailed the scene. Just nailed it. But I said to him afterward, ‘Hey, are you O.K.?’ And he said something like, ‘It’s no fun getting old. And I am so f-cking old.’ But he said it in one of his funny voices, like he was some ancient old guy. Like it was a joke.”

CBS canceled The Crazy Ones in May. Two months later, Williams checked himself into his final rehab, seeking to “fine-tune” his commitment to sobriety. Comedians, whether or not they become movie stars, are also actors: onstage alone, before a crowd that could be bored or hostile, they play characters that must be commanding or charming enough to win laughs and love. Offstage, they can be quiet or morose, and that could be Williams. “If you were alone with Robin,” says Zmuda, “and I’ve known this guy for 35 years, he would be so uncomfortable. It would be like being in an elevator with a stranger. But if there were two people in the room, then he would snap into performing. I think he was a guy who had a very difficult time if he was alone.”

The man who could play anyone could not play only one: not only Robin Williams, whoever they were. He entertained the comic cacophony in his head, nearly as much as it entertained his fans. And then the voices told this Pierrot-Hamlet it was time for a rest. The rest is silence.

Williams called himself an Episcopalian–he once created a Top 10 Reasons to Be an Episcopalian (“No. 3: All of the pageantry, none of the guilt”)–and imagined the afterlife as a posh restaurant, observing, “Death is Nature’s way of saying, ‘Your table is ready.'” He bequeathed that eerie optimism to Zelda, who the day after her father’s death posted a passage from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s children’s classic, The Little Prince. It speaks of farewell but not goodbye, with the twinkling promise of mirth after death: “You–you alone will have the stars as no one else has them … In one of the stars I shall be living. In one of them I shall be laughing. And so it will be as if all the stars were laughing, when you look at the sky at night … You–only you–will have the stars that can laugh.”

Just now we can cry for the man, for the torments he endured and the broken hearts of his family. But we would be wrong to remember him only as Robin Williams, Suicide. That would deny the best in ourselves–an inspired portion of which he planted there. On one episode of Mork & Mindy, Mork speaks with his (unseen) Orkan contact Orson about his sorrow over losing a friend. “You know,” he says, crushed by bereavement, “when you create someone, you nurture them, they grow, and then there comes a time when they have to lead their own life.” His voice breaks as he adds, “Or die their own death.” Orson asks, “And now your friend is gone forever?” “No, Sir,” Mork whispers, pounding his heart. “I’ll always keep him right here.”

So we recall Robin Williams as the stalwart friend whose generosity matched his genius, and the star who corralled his angels and demons to make the world laugh in the maddest, merriest way. Our friend isn’t gone forever. We’ll always keep him right here.

–WITH REPORTING BY SARAH BEGLEY, KATE COYNE, ERIC DODDS, NOLAN FEENEY, LARRY GETLEN AND LAURA LANE/NEW YORK; J.D. HEYMAN AND LYNETTE RICE/LOS ANGELES; AND KATY STEINMETZ/MARIN, CALIF.

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly described Robin Williams’ role in The Fisher King.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com