You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content? Click here.

The U.S. has a ruling class. It is cloaked in a conspiracy of silence. It is a generation that dares not, or prefers not, to speak its name—middle age. Yet it is that one-fifth of the nation between the ages of 40 and 60 (42,800,000) who occupy the seats of power, foot the bills, and make the decisions that profoundly affect how the other four-fifths live. The halls of Congress ring with the medicares of the aged. Every anatomical twitch or psychedelic escapade of the teen-agers scares up worry wart headlines. Ironically, even the revolt of the teen-aged is subsidized by middle-agers. Those tiny secessionist principalities of the disdainful young that span the U.S. from the La Jolla, Calif., surfing set to the hobohemians of Greenwich Village could scarcely be sustained without the checkbooks of indulgent fathers.

In a perceptive commencement address delivered at N.Y.U. last month, Assistant Dean Milton R. Stern noted: “The young seem always to be in the public prints and on TV, but that doesn’t mean that they control things. To the extent that young people wearing their hair longer or skirts shorter dominate the mass media, they are frequently being exploited for commercial reasons. Youth is used to sell—perfumes, cars, cigarettes, and everything else. Youth, indeed, learns to sell itself. What happens to the young people these days is the opposite of commercialized vice—it might be called commercialized innocence.” The middle-agers attract little attention, inspire few learned treatises as to the state of their being—good, bad, or indifferent. Paradoxically, middle-agers are the invisible Indispensables.

Steps Steeper, Print Smaller. No one has had time to study middle age very much, since it is practically a modern invention, as well as a distinctly American one. Prehistoric man lived about 18 years. The life span of an ancient Greek or Roman averaged out to 33. When friends attempted to dissuade Cato the Younger from committing suicide at 48, he argued that he had already outlived most of his contemporaries. Even as recently as 1900, U.S. life expectancy was less than 50. Thanks to medical advances and high-protein diets, life has lengthened, and it has grown in the middle.

As to where the middle starts, medical theory is very sketchy, and any age grouping is arbitrary, more of a social and psychological norm than a physiological fact.

When does middle age begin?

“When all the policemen look young,” says Leo Rosten, 58, creator of H*Y*M*A*N K*A*P*L*A*N. “And to me they’re mere children.”

“When the steps get steeper and the print gets smaller,” says Whitney Young Jr., 45, executive director of the National Urban League.

“I’ll let you know when I get there,” snaps New York’s Mayor Lindsay, 44.

In physical strength a man peaks at 21 and plateaus to the late 60s, the period when degenerative diseases stalk. The arduous training program of the astronauts, five of whom are over 40 (Walter Schirra, Alan Shepard, Donald Slayton, Scott Carpenter, Virgil Grissom), has proved that a man can double his normal physical competence at ages much beyond 21. Any middle-ager’s physiological potential is probably as unique as his fingerprints. The hair may grow thinner, but the capacity for mental growth is unimpaired in middle age. It is obvious that a man or woman of 40 can understand Moby Dick, The Waste Land or Ulysses (which was published on James Joyce’s 40th birthday) far better than the 18-year-old who is assigned it in freshman English.

Survivors at the Banquet. Over the past three decades, the concept of the middle years has vastly changed. In 1932, Walter B. Pitkin wrote Life Begins at Forty and it became an overnight inspirational bestseller, precisely because people thought life ended at 40 and there was nothing left to do but wait around for retirement and death. Perhaps no single figure stamped the modern view of middle age upon the era more forcefully than John F. Kennedy. He represented the generation, seasoned by World War II and tempered by 20th century adversity and affluence, that is now in command.

Senior members of the generation, now in their 50s, bear some added marks. “We were the Depression people,” explains one. “In a way, we have the good-natured gaiety of survivors.” Together they make up the generation of the middle years, of the flexible mind, the resilient spirit and the high heart. It has the assurance of having been tested and not found wanting. In its quenchless vitality, it drinks up the golden decades like nectar at the banquet table of life. It is invisible because it defies chronology. It measures age not by a date on a calendar but by a dance of the mind. Just prior to last week’s marriage of Frank Sinatra, 50, to Mia Farrow, 21, Mia’s mother Maureen O’Sullivan, 55, was asked how she felt about the 29-year age discrepancy. Said she: “It means nothing. I know people who are antiques at 35 and others who can watusi at 70.”

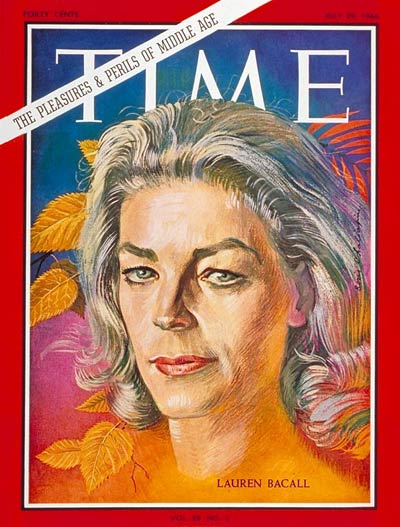

Authentic & Beguilingly Lovely. It is this mercury of the spirit, this added luster of vitality that adorns the beauty within the beauty of Lauren Bacall. The theatergoers who have made her Broadway comedy Cactus Flower an S.R.O. hit since the night it opened seven months ago do not think of Bacall as a woman of 41, nor does she, nor does the amorous dentist-hero of the play, Barry Nelson, 44, whom she guilefully lures away from a mistress half her age.

What is fascinating about Bacall is not so much her kinetic sea-green eyes or her svelte-as-sin 129-lb. body, but the distillation of glamour into poise, inner amusement, and enriched femininity that no 20-year-old sex kitten has lived long enough to acquire. Playgoers can sense the discipline that shapes her performance, the reliable professionalism of the middle years, so that in her deft command of her craft as an actress-comedienne she is an authentic as well as beguilingly lovely symbol of the generation.

All Cliché, All True. The view from Lauren Bacall Bogart Robards’ high-ceilinged fourth-floor apartment in the Dakota, Manhattan’s imposing fortress of old-world luxury, is the dense green foliage of Central Park. For Betty Bacall, as her friends call her, the view from the 41st year is just as vernal. Little Sam, her four-year-old son by Jason Robards, trots into the room with his nurse for some hugs and kisses before being taken for a row on the park pond. As he pauses at the door, his mother says, “Throw me a kiss.” Sam runs back into the room. “I wouldn’t throw you a kiss,” he murmurs, giving her a last affectionate smack.

At this moment, Betty Bacall is delighted with her life. “I’ve waited for this for 40,000 years,” she says, meaning Broadway stardom. “It was my teen-age dream.” Actually, it is her third career. Born in New York of a Russian-Polish medical-supplies salesman and his Rumanian wife, Betty Joan Perske, as she was then named, was an only child. The parents soon divorced and Betty, who has not seen her father since she was eight, was reared by her mother. She attended New York public schools, a Tarrytown, N.Y., boarding school called Highland Manor, and graduated from New York City’s Julia Richman High School. She began modeling when she was twelve, “to make a little dough,” and had graced the cover of Harper’s Bazaar by the time she went to Hollywood at 18. In her very first film, To Have and Have Not (1945), she added a classic come-on line to U.S. cinema legend, and anyone who heard her utter it the first time around fully qualifies as middleaged: “If you want anything, just whistle.” Humphrey Bogart wanted her.

“If two people love each other,” Hemingway once wrote, “there can be no happy end to it,” meaning one must die before the other. “Being a widow is no picnic,” says Betty Bacall, “you lose your place,” a shattering experience that has befallen 1,900,000 women in the 40-to-60 age group. “I had to go on because of my children, and I had to because of my own sense of survival. Bogey’s belief always was that if one mourns too long, one mourns for oneself rather than for the one who’s gone. Life is for the living. It’s all a cliché, but it’s true.”

A Time for Ultimatums. Luckier than most widows with two children (Stephen, now 17 and Leslie, 13) can hope to be, she met and married Jason Robards, a splendid actor and the most sensitive interpreter of O’Neill characters on the U.S. stage. A few years ago, while not yet middleaged, she found herself drifting into the crisis of purposelessness that afflicts many women in their middle years: “I lost sight of myself as a woman, as an actress—even in my friendships I was neglectful. I knew I wasn’t functioning well. I became rundown physically. When you have the responsibility of a husband and children, you also have a responsibility to yourself. If you neglect yourself, you actually are neglecting them. It’s unfair to all.”

So Betty Bacall issued a brisk ultimatum to herself: “Damn it, straighten up! Pull yourself together and point yourself in the right direction. MOVE!” The move was back to work: “It helped me enormously. There’s always something about making a decision in your life. It takes a load off your back.” At work she found herself possessed of one of the strengths peculiar to the middle years: “It is necessary for anyone to practice his craft to do it well and to improve. But also, in a strange way you have to live a certain amount of life, and even if you don’t practice your craft you have lived, and when you go back you find you have learned something.”

What has Bacall learned to value in her lifetime? “Character and a sense of humor are the two things that will carry you through.” Her own wryly self-deflating humor (“It takes the sting out of things that hurt”) neatly defines the dividing line between generations. The young laugh at the way things seem; the middle-aged laugh at the way things are. What are her pleasures apart from husband, children, work and friends? “I’m an insane furniture and bibelot buyer. I love the ocean—it’s one of the last free places on earth.” Betty Bacall has also learned the ultimate wisdom of the middle years, to live in the here and now: “There are things in life that are pretty rotten. The part that’s good you’ve got to enjoy while you have it.”

Mold & Shape. Without the Bacall good looks but with the selfsame vitality, other members of the command generation are the helmsmen of U.S. society in government, politics, education, religion, science, business, industry and communications. From President Johnson, 57, and Vice President Humphrey, 55, through the entire Cabinet including Rusk, 57, and McNamara, 50, the top echelon of government is middleaged. Including that anachronistic middle-ager, Bobby Kennedy, 40, the 100 U.S. Senators tally up an average age of 57, and the House of Representatives is seven years younger at a representative 50. Sixty-three percent of this country’s Nobel prizewinners in the past ten years have been between 40 and 60. At 15 of the leading U.S. colleges and universities, the average presidential age is 55; of 900 executives in 300 top corporations, only a handful falls outside the 40-60 group.

Today’s top-responsibility middle-ager might say with Shakespeare’s Henry V at dawn of the Battle of Agincourt: “The day, my friends, and all things wait for me.” Whether the hand holds the scalpel (Dr. Michael DeBakey, 57) or the baton (Leonard Bernstein, 48), it is watched by patient and public with rapt attention. Whether he is a Protestant evangelist (Billy Graham, 47) or a Catholic Archbishop (John Patrick Cody, 58, of Chicago, a U.S. cardinal-to-be), he lends spiritual guidance to attending multitudes. Whether he is a master of industry (Arjay Miller, 50, president of Ford) or a master of jurisprudence (Byron R. “Whizzer” White, 49, Supreme Court Justice), he determines the patterns of social change. Whether the opinion molder is at the University of Toronto (Marshall McLuhan, 55) or on Madison Avenue (David Ogilvy, 55), he shapes the thoughts and desires of a continent.

Positioning the Lever. It may seem axiomatic that the middle-aged are in control. It was not always so. John Paul Jones was in command of his own ship at 21, and Pitt the Younger was Prime Minister of England at 24. But complex technologies and lengthy professional studies have forced young men to play the waiting game. Also, they have lost what Lexicographer Bergen Evans notes was “the fastest path of advancement—dead men’s shoes.” In Europe and Asia, the old still hold sway. In the heart of Europe, De Gaulle is in full command at 75, and it is unlikely that Germany would defy ex-Chancellor Adenauer at 90.

Power, in a far less grandiose sense, is one of the daily pleasures of the middle-ager. Adept at his job, he has learned how to channel his energy, and can place Archimedes’ lever in the exact spot that will shift the world a trifle closer to his heart’s desire.

Delight & Risk. No man in the land gets a higher paycheck than the middle-ager. The average age for incomes of $10,000 to $15,000 is 47, for incomes of $15,000 and up, 51. This makes delayed pleasures possible. A man may have been sports-car minded for years, but when he climbs behind the wheel of a Mustang, his average age is 48. With no small children underfoot, husbands and wives discover the pleasures of each other’s company, share convention trips, take that second honeymoon to Europe.

Change is a delight in the middle years. Columnist Art Buchwald, 40, pulled up stakes in Paris as the celebrity’s celebrity, relocated himself in Washington, D.C., and mined it for satire. Astronaut John Glenn, 45, is a vice president of Royal Crown Cola. Sometimes the change is an allout risk. Maxwell Wihnyk, 54, was running a mildly profitable newspaper in Beaumont, Calif., five years ago, but there was no joy in it. With a wife and three dependent children, he decided to go to law school. Says he: “You can scare the hell out of yourself living off capital for three years; in fact, the only way to do it is not to think about it.” Armed with a degree from the U.C.L.A. law school, he is now set up in a modest but personally satisfying law practice in Beaumont.

It is pretty quaint to recall that Franklin P. Adams said: “Middle age occurs when you are too young to take up golf and too old to rush up to the net.” Today’s middle-agers not only dot the greens, they vault the net. They sail, ski, waterski, skin-dive and spelunk. They swim, walk and climb. They fish, hunt, camp and swarm all over the great outdoors from Big Sur to Cape Cod. They are a participating rather than a spectator generation.

Before 40, one adds and feeds to gorge the ego; after 40, one subtracts and simplifies to slim the soul. With the final image of one’s existence even faintly in view, the self seems pettier and the words “service,” “love of others,” “compassion” not only creep into the middle-ager’s vocabulary but add meaning to his life. In church work, social work, community fund drives, culture centers, middle-agers are always at the fore. Sol Linowitz, 52, chairman of the executive committee of Xerox Corp., defines his abiding purpose: “I want to leave the world a little better place than I found it.”

Frustration Is Shirking. “When I was young, the whole world revolved around my, my, my,” says Columnist Ann Landers, 48. “Today, I don’t think in terms of myself but rather how I can be part of something bigger and better.” She echoes G. B. Shaw’s creed: “Happiness, a paltry goal. The thing is to be used, spent, squandered in the splendor of one of life’s consuming causes.”

Sometimes a middle-ager finds that meaningful cause in adversity. Four years ago, Lynn Selwyn, now 40, was apathetic, morose, and her marriage was irreparably cracked up. One day, Jeanne Cagney, sister of Jimmy, said to her: “Frustration is the shirking of potentiality.” Says Lynn: “In that instant I knew I had to do something with my life, learn how to live without being dependent on someone else.”

With two other women, she founded Everywoman’s Village in Van Nuys, Calif. It consists of a grassless half-acre, six bungalows, and a staff of 15 teachers who give courses ranging from ballet, oil painting, psychology and foreign languages to exotica like yoga and flowered bead making. The classes are limited to 15, the atmosphere is totally informal and there are no grades. The school’s aim is to be a link between the housewife and the university. “Most housewives are afraid to resume their education in a formal classroom,” says Lynn, “because they feel threatened by the bright-eyed 19-year-olds. The Village is a steppingstone, the first step for the woman trying to get out of the kitchen. We want to stimulate self-growth and human development.”

Wisdom & Panic. As Aristotle once pointed out, there are no boy philosophers. One of the philosophical satisfactions of middle age is not being young. The sign of health for the middle-ager is that he prefers his own age; he has no desire to go back to 20 because he knows what 20 is in a way that 20 does not. It is a difference in perspective: youth’s is flat, middle-age’s is three-dimensional. It is the difference between ignorance and wisdom, impulse and judgment. The young think there is no tomorrow; middle age knows there is tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow. The young want to dynamite the treasure vaults of life; middle age has learned the combination. The young think they know; middle age knows that no one knows.

If the middle years can be wise and felicitous, they can also be foolish and frantic, fraught with nerve-frazzling doubts and despairs, somber with peril and melancholy. The middle-ager usually knows better than to stay up till 4 a.m., but he sometimes finds himself waking up at 4 or 5 a.m. in a swivet of inexplicable panic. He has reached the age of what T. S. Eliot called the hoo-ha’s:

When you’re alone in the middle of

the night and you wake in a sweat

and a hell of a fright

When you’re alone in the middle of

the bed and you wake like someone

hit you on the head

You’ve had a cream of a nightmare

dream and you’ve got the hoo-ha’s

coming to you.

Into the Televoid. Of course, there are His and Her hoo-ha’s. The woman is faced with the fact and fear of a major physiological change, the menopause. The foremost cause among the middle-aged for first admissions to mental institutions is listed with the diagnosis “involutional psychosis,” sometimes called “change-of-life melancholia.” If her children are in their teens, the shadow of becoming an “empty nester” also falls across her spirit. She is becoming one of nature’s unemployables, threatened both in her womanliness and in her family’s need of her. “But what should a woman do after her children are grown?” asks Lynn Selwyn. “Should she shrivel up and die?”

This private womanly plight has become a vociferous public debate. Hold on to a job, coaches Betty Friedan (The Feminine Mystique). Come back for a refresher course, coaxes Radcliffe’s Mary Bunting. Amid the pelted advice, there is a tendency to forget that many women are not equipped to do either. For them, the years of the hoo-ha’s may consist of face lifts, hair tints, silicone shots, quack religions, quack diets, forever gazing, as Louis Auchincloss has put it, “over a sea of card tables” or blankly into the televoid.

The Gods Prove Intractable. When the hoo-ha’s hit a man, he thumbs through his immediate worries: mortgages, unpaid bills, the children’s education, the stab of a chest pain that could be a heart attack, the state of his marriage and job. But the free-floating anxiety that seeps into a man’s bones at the onset of the middle years cannot be pinned to any one of these specific causes. Cyril Connolly calls 40 the age of saints and suicides. Eric Berne (Games People Play) calls it the time when people play “Balance Sheet.”

What each is saying, in his different way, is that it is a climactic period of stocktaking, an often agonizing reappraisal of how one’s achievements measure up against one’s goals, and of the entire system of values one has lived by. What drastically confronts a middle-aged man at this moment is how the choices of the past have robbed him of choice in the present.

As a young man, he was a creature of infinite possibilities, and his dreams spangled the future like stars. In his 40s, he must live with one actuality—he is the fruit of his limitations. In his 30s, a man can still blame his luck and jolly himself along with the notion that, by unremitting work and determination, he will lick the gods and win the top prizes. The gods prove intractable, and in his 40s, a man is forced to acknowledge that he has done pretty much what he was capable of doing. More depressing, he knows that he will have to go on doing it with ever-brighter, ever-younger men nipping at his heels.

Fate’s Straitjacket. Just how frustrated a middle-ager may feel in such a situation is amply documented in a book about the trials and torments of the middle years, called The Middle-Aged Crisis by Barbara Fried, which will be published in the spring of 1967. Mrs. Fried, 42, a psychology editor, interviewed countless middle-agers on their problems, and frequently encountered an unhappy sense of betrayal: “Sure I feel trapped. Why shouldn’t I? Twenty-five years ago, a dopey 18-year-old college kid made up his mind that I was going to be a dentist. So now here I am, a dentist. I’m stuck. What I want to know is: who told that kid he could decide what I was going to do with the rest of my life?”

The trapped middle-ager wants to flee, like Gauguin to the South Seas, but erstwhile bankers of 45 who desert their Parisian families and become great painters are one of a kind. To blunt the pain of reality, he slips a whisky bottle into his desk and nips at it. (Alcoholism climbs a steep 50% in the 40-60 group over ages 30-39.) His medicine cabinet begins to look like a pharmaceutical display, and he retreats into hypochondria. Indeed, the sense of being straitjacketed by fate may contribute sizably to the cardiovascular and cardiopulmonary attacks that increasingly fell middle-agers.

Race Against Time. The trapped middle-ager is introspective, resigned, and rebellious all at the same time. Modern literature and drama vividly depict his psychic desperation, from Bellow’s Herzog to Miller’s After the Fall, from Albee’s Virginia Woolf to Osborne’s Inadmissible Evidence, from the novels of John Marquand to the novels of John O’Hara. John Cheever, who writes of middle age with autumnal sadness, is its prose laureate. In O Youth and Beauty!, he tells of the ritual of Cash Bentley, a former track star turned 40 who, when the Saturday-night suburban party was guttering out between the empty gin bottles and the full ashtrays, would pile the furniture together in clumps and at a friend’s revolver shot, go hurdling over it.

This is Cash Bentley’s race against time, and he “ran it alone, but it was extraordinary to see this man of forty surmount so many obstacles so gracefully.” At one party, he fails to clear a chest and slams to the floor, breaking his leg. He recovers, a morose and different man. Late one night at home, he is obsessed with running the race again. He hands the revolver to his wife, who is unfamiliar with it. With a hurried instruction about the safety catch, he is off. She shoots him dead in mid-air over the sofa.

Reverse Oedipal Tide. Most middle-agers do not fight the clock as fatally as Cash Bentley, but many try to turn it back. Some middle-aged husbands decide that not time, but their wives, are sapping their lives. This is the age of the domestic tirade, à la Virginia Woolf. The wife feels neglected, the husband feels nagged, both feel thoroughly bored with each other. According to Dr. Masters and Psychologist Johnson in Human Sexual Response, there is a marked flagging of male potency in the 40s, but it is not so much physical as psychic impotence.

Psychoanalysts argue that both sexes enter a sort of second adolescence in the mid-40s, but the male has more sexual options. A kind of reverse Oedipal tide may run. Where he once craved his father’s power, he may now covet his teen-ager son’s potency. The sight of a young couple embracing in the park stabs him with a pang of envy. Meanwhile, he mercilessly scrutinizes every sag, bulge, and wrinkle that makes his wife unappetizing. In The Revolt of the Middle-Aged Man, Dr. Edmund Bergler records the rebel’s plaint: “I want happiness, love, approval, admiration, sex, youth. All this is denied me in this stale marriage to an elderly, sickly, complaining, nagging wife. Let’s get rid of her, start life all over again with another woman.” Home-wrecking is an inside job.

The Cruelest Jest. The stage is set for the extramarital affair, frequently the office romance. The office romance thrives on contiguity, opportunity, and the fact that love feeds on shared experience. The man looks across the desk at this sweet young thing, and she stirs memories of playful erotic tenderness before he pulled on the heavy, encumbering armor of duty and responsibility. Whatever the wife is doing on her rounds, the husband and his secretary are doing something in common that draws them intensively closer, whether it is planning an ad layout or drafting a new skyscraper. Assuming the girl is about 20 years younger than the man, she is apt to find him not only more affluent, but considerably more interesting company than the boys in her own age group. It is worth remembering that it was on the set of To Have and Have Not that Bogey, married and 44, and Betty, single and 19, fell in love.

However, the extramarital affair does not lead straight to the divorce court. The median divorce age in the U.S. is 32. In the 40s and 50s, divorce is major surgery, and a man is reluctant to cut that much life out of his life. Besides, time sometimes taunts the older lover with the crudest of jests. Having roused the ardor of a younger woman, he may find himself no match for her physical demands and end up more ruefully conscious of his age than when he set out to refute it.

Easing Ahead. The stresses and strains of the middle years may be considerably eased in the decade or two ahead. Dramatic changes are certain. Biologically, the systematic use of hormones may phase out woman’s change-of-life crisis and make the menopausal trauma a thing of the past. If the point of view that inspired the 1965 federal antidiscriminatory legislation on the hiring of older men flourishes, middle-aged men will be rid of the fear they now legitimately have that being fired, or quitting a job after 40, means a long, scary interlude in limbo before getting rehired. Transitional schools like Lynn Selwyn’s Everywoman’s Village may help reorient women who see their grown children as their epitaph. The cultural explosion will give more middle-agers secondary interests in the arts, those exciting openers of the mind’s eye that keep the human horizon from shriveling.

What might make middle age pleasantest of all is a reform that middle-agers could institute themselves. Middle-agers need prestige as well as power within U.S. society. They need to have their age role approved by those around them rather than feel defensive and self-conscious about it. What militates against this is the Youth Cult.

The Youth Cult is intimately related to the American denial of death. Europe has escaped it so far by retaining the tragic sense of life. There it is recognized that each age has its unique joys and charms, and the entire span of life is valued as equally precious. In the U.S., the Youth Cult marches from trick to trick, the latest being a preparation called “Great Day,” by which a man can rinse that grey right out of his hair.

It might be called Dorian Gray. It is true that Dorian Gray never grew old. His tragedy was that he never grew. Earthly immortality is a pathetic mirage. Time will not stop. In an attempt to stop it, one merely stunts one’s self. The ultimate victims of the Youth Cult are the young, some of whom believe that turning 25 is the outer limit of human obsolescence. The Youth Cult misleads them into thinking that license is freedom, that untutored whims are tastes, and that ever-jittering motions are deeds. Since it is the specific problem and task of middle-agers to induct the promising young into the society of civilized men, it might be a boon to all generations to begin by debunking the stultifying Youth Cult.

Hallmark of Humor. In attempting to measure the ground between 50 and 20, Adlai Stevenson once put it this way to the students of Princeton: “What a man knows at 50 that he did not know at 20 boils down to something like this: the knowledge that he has acquired with age is not the knowledge of formulas, or forms of words, but of people, places, actions—a knowledge not gained by words but by touch, sight, sound, victories, failures, sleeplessness, devotion, love—the human experiences and emotions of this earth; and perhaps, too, a little faith and a little reverence for the things you cannot see.”

Ask Lauren Bacall what she is going to do with the next 20 years and her mouth twists in a self-amused grimace: “Try to survive—for openers.” The humor is symptomatic and the understatement characteristic. The generation that is in command has little taste for mock heroics and even less for overstatement. Its eyes are relatively clear, if at times somewhat troubled. Its productive record is vast and its potential still enormous. While at times it may seem hesitant and confused, it has pride in its competence, intelligence and tenacity, and staunch confidence in the future.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com