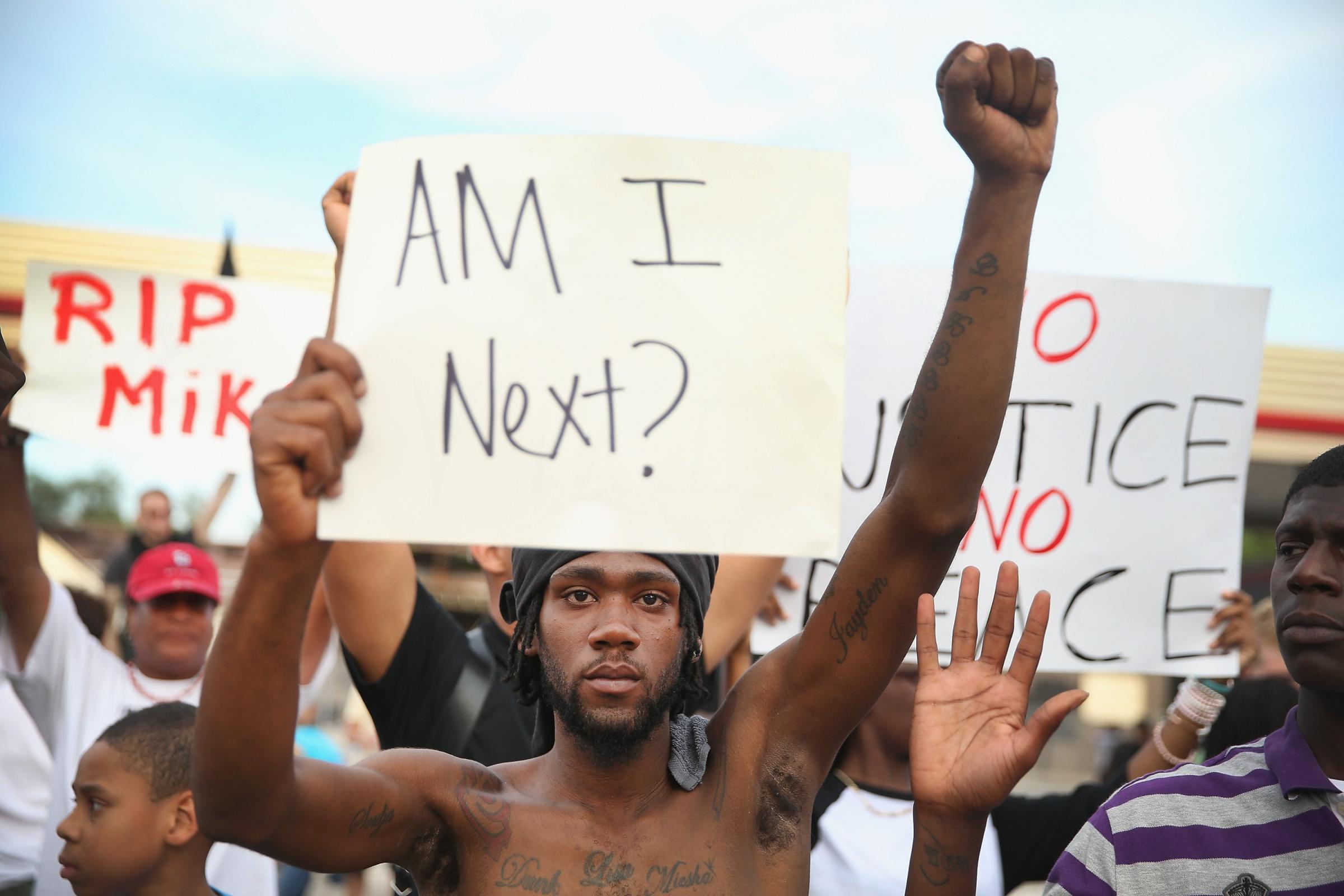

Officials in St. Louis County and the tense town of Ferguson, Mo., remain mum nearly three days after an unidentified police officer shot an unarmed black teenager to death. But a young man who says he was with the victim at the time of the shooting has described a virtually unprovoked attack in which the officer fired repeatedly — even after the victim raised his hands and begged him to stop shooting.

In an interview with MSNBC, Dorion Johnson, 22, said his friend Michael Brown, 18, was walking in the street when the officer ordered him to the sidewalk. When Brown did not immediately comply, the officer put him in a chokehold. The young man struggled to free himself, and the officer pulled his gun and fired.

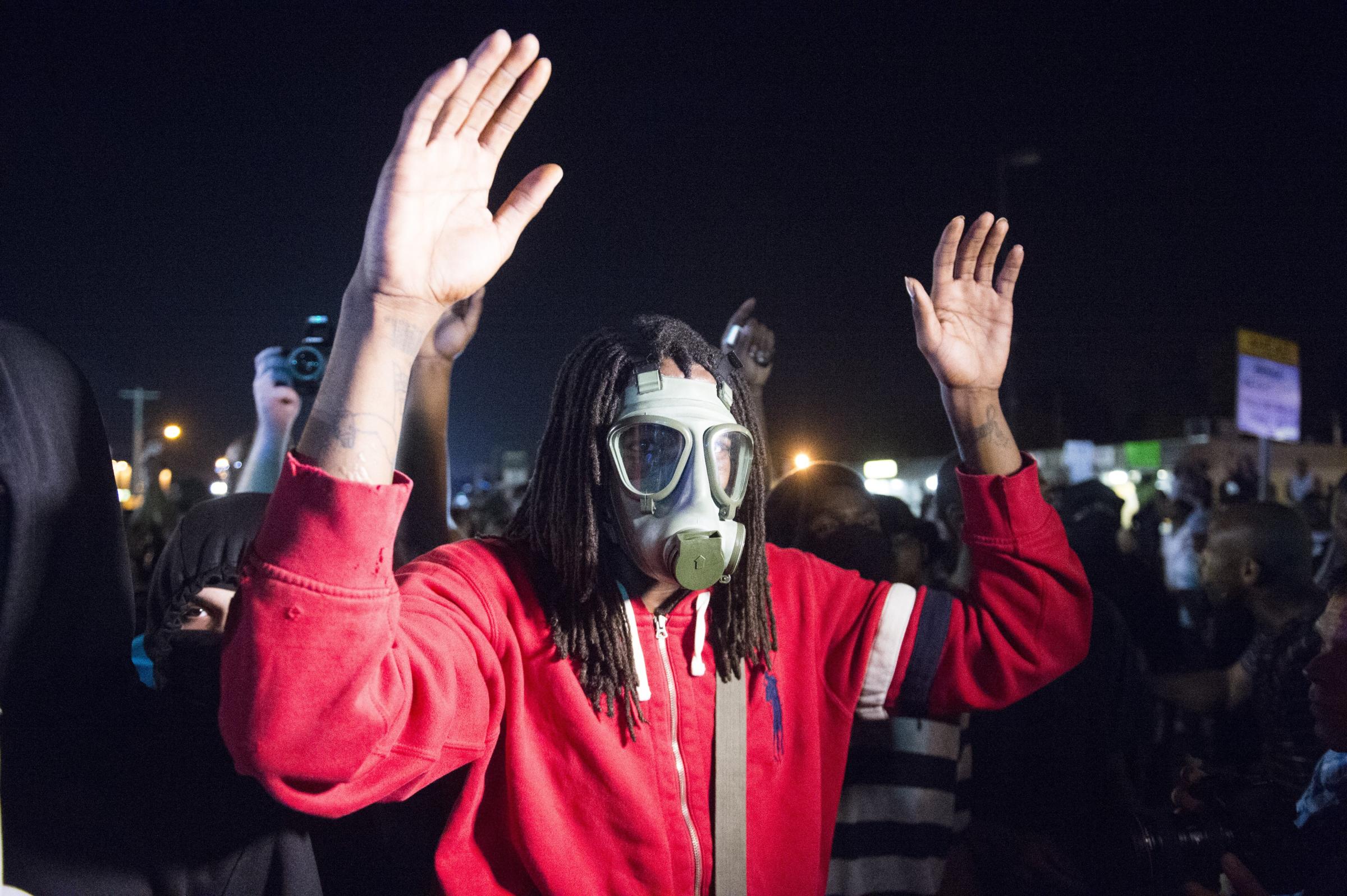

Wounded, Brown tried to flee but was shot a second time in the back. That’s when he turned with his hands raised, Johnson said. “I don’t have a gun. Stop shooting!” he said, but additional shots were fired.

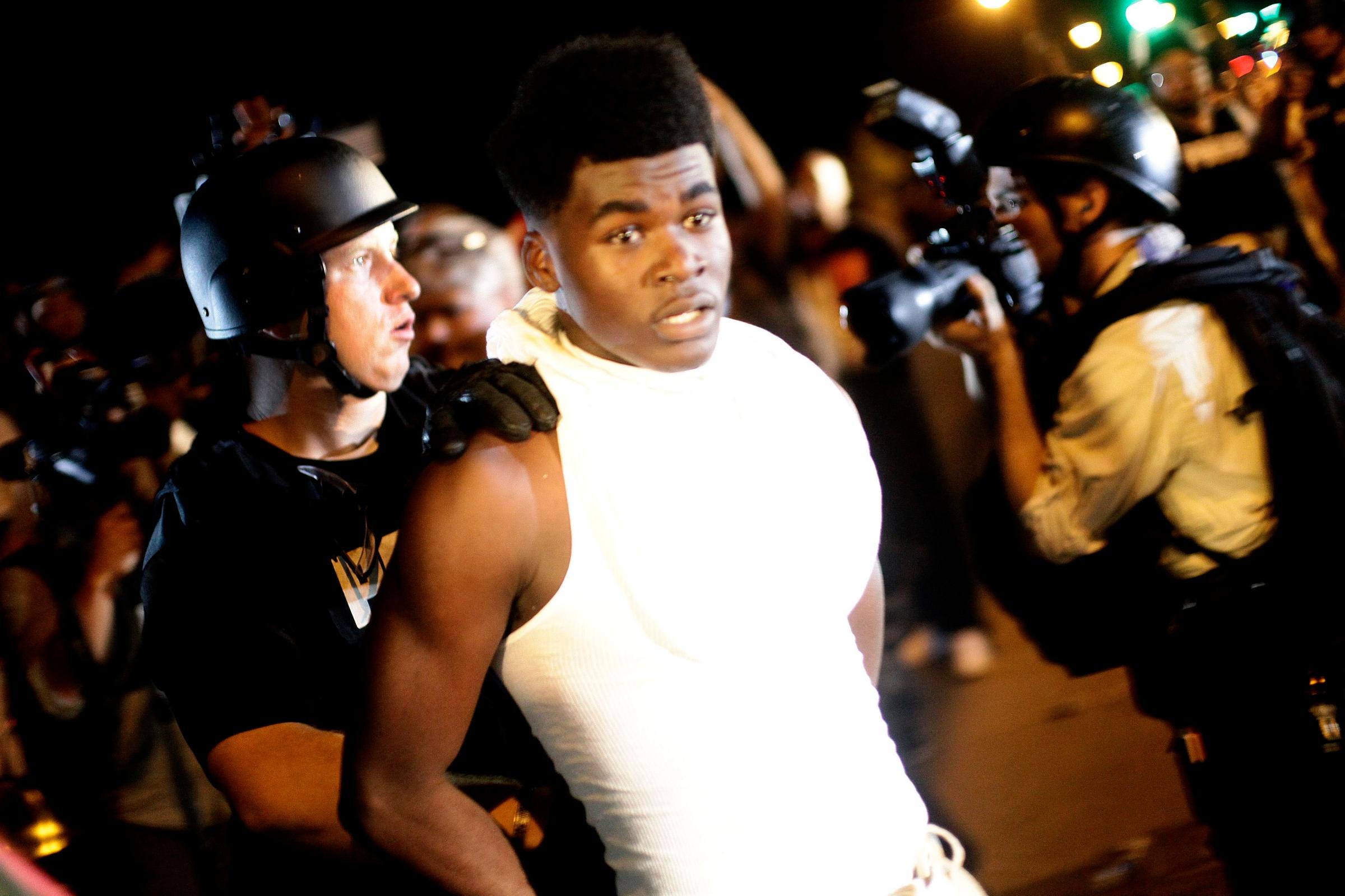

Johnson’s version of events entered an information vacuum created by the silence of city, county, state and federal officials. Ferguson police chief Thomas Jackson said Monday that information concerning Brown’s death would be released by noon on Tuesday. But as the deadline approached, a department spokesman announced a change of plans. The officer involved will not be named, nor will authorities commit to a timeline for releasing autopsy results and other details of the investigation.

Citing threats lodged on social media, Ferguson police spokesman officer Timothy Zoll said, “we are protecting the officer’s safety by not releasing the name.”

The St. Louis County police were also mum. Their investigation into the shooting continues, said officer Brian Schellman, “but it is not for us to release the officer’s name. It is a personnel matter. It is up to the Ferguson police.”

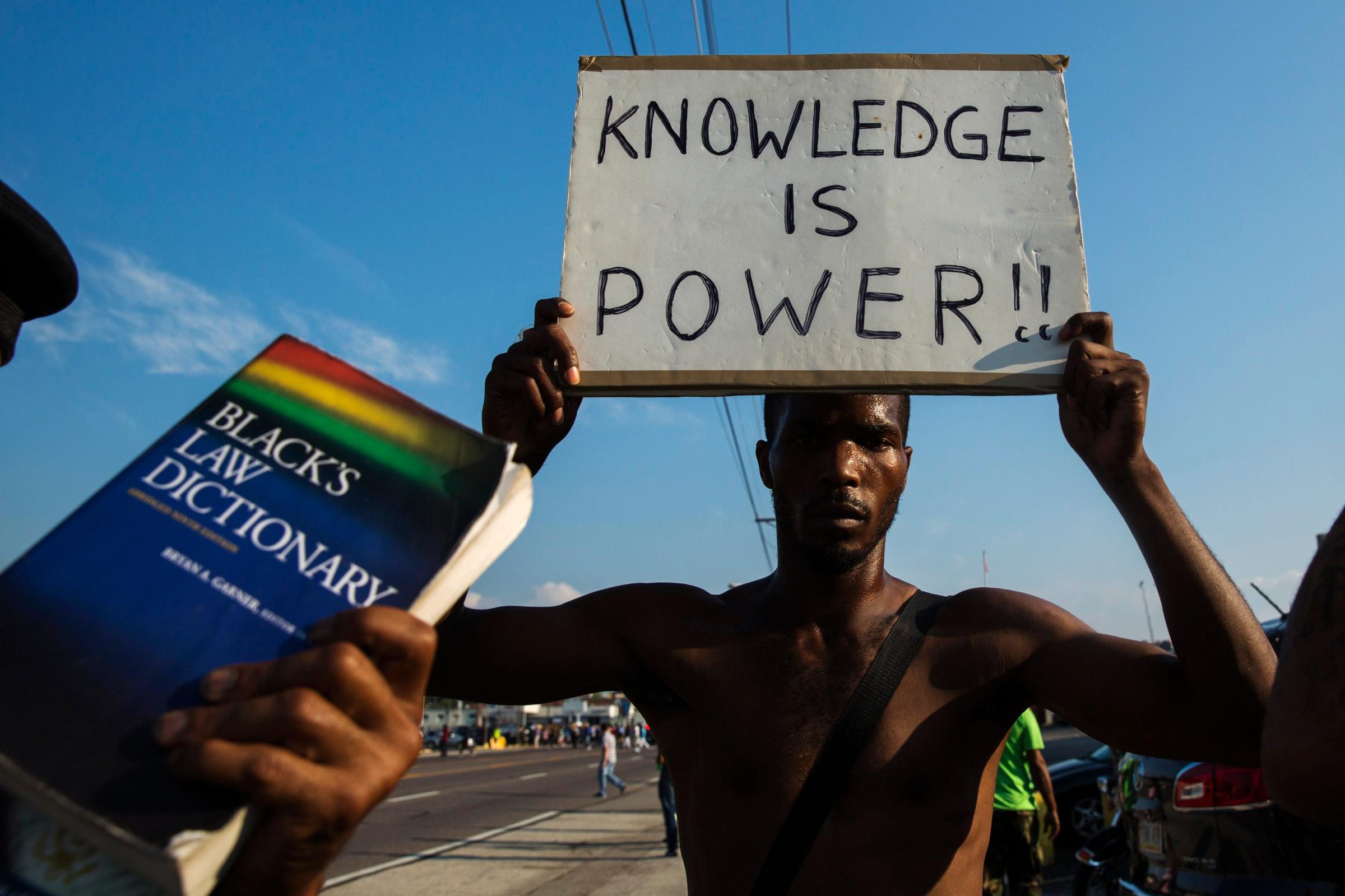

At a press conference on the steps of the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis on Tuesday, the Rev. Al Sharpton and Benjamin Crump, a civil-rights lawyer representing Brown’s family, said they are considering suing the Ferguson police for the release of the officer’s name. Citing community distrust of local law enforcement, Crump called for the Justice Department to take over the investigation.

This investigation has been more complicated than most, as police have been pressed into a struggle to maintain peace in a restless and angry community. On Sunday night, peaceful protests erupted into a chaotic scene of arson and looting. Since then, parts of Ferguson — an incorporated working-class suburb of some 21,000 residents roughly 12 miles north of St. Louis — have been patrolled by scores of armored police officers with tear gas at the ready.

“This isn’t what Ferguson is about,” said one resident, Shante Duncan, 33. “This is a good community. There are lots of people on the ground doing good work, but you never hear about any of it.”

Generations of racially mixed families have lived in Ferguson, some dating back more than a century, with ancestors among the slaves who were sold at auction houses on the Mississippi riverfront. Today, its residents comprise roughly two-thirds African Americans and one-third Caucasians. Race relations, often harmonious among neighbors, are frequently tense between black residents and the mostly Caucasian city officials.

“Ferguson is notorious for being prejudiced against blacks,” said George Chapman, a 50-year-old African American who has lived in the town most of his life but said he recently moved because he was “tired of the police.”

“The police stop us all the time,” Chapman said. “The police show us no respect. They treat us like we’re nothing.”

A racial-profiling report from the Missouri attorney general’s office showed that, last year, African Americans in Ferguson were significantly more likely to be involved in police traffic stops and arrests.

Michael Brown’s parents said during a press conference on Monday that their son had overcome the racial hardships facing many young African-American males. “He was a good boy,” said his father Mike Brown Sr., determined to make something of himself and scheduled to start schooling for a career in heating and cooling.

“He was starting on a new journey,” said Brown’s mother Lesley McSpadden. “He was maturing.”

Brown’s family deplored the looted businesses in Ferguson, the violence, the vandalism that resulted in boarded-up businesses and scrawled graffiti inciting violence against police. “Why would you burn your community?” asked Brown’s grandfather, Leslie McSpadden. “Why? This should not be his legacy.”

Why, indeed. St. Louis is not the first place most Americans would name when asked to think of a city primed to blow. But friction is the result of two surfaces rubbing together, and St. Louis has always been a city where surfaces meet. It may be the ultimate border town. Its signature arch, marking the Gateway to the West, is meant to remind us that St. Louis is the place where the East ended and the West began. Likewise, its equipoise near the midpoint of the Mississippi marked St. Louis as a fault line between North and South.

The racial history of St. Louis is burdened by a hyperconsciousness of borders and boundaries. Colin Gordon of the University of Iowa brilliantly demonstrates this in his book (and related website), Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of the American City. Few cities, as Gordon shows, have taken a more systematic approach to racial separation and division.

It started with … well, how far back do we want to go? The infamous Dred Scott case of 1857 — that spark in the powder keg of the Civil War — began in St. Louis as a question of whether a man’s human rights evaporated when he crossed the border into a slave state. In the decades since that terrible war, St. Louis has tried a number of tactics to keep the races apart.

In 1916, the city passed a zoning law that explicitly restricted black homeowners to certain neighborhoods. The following year, in a case out of Louisville, Ky., the Supreme Court struck down racial zoning laws. So St. Louis realtors responded with a series of restrictive covenants designed to separate the races. White homeowners were forbidden to sell their houses to black customers, and real estate agents could lose their licenses if they participated in a forbidden transaction.

Eventually the covenant strategy failed as well. In 1946, the Supreme Court struck down those arrangements in a case that came from St. Louis.

Now the metropolis turned to redlining, the practice of steering black buyers into certain neighborhoods by discriminating on their mortgage applications. Through it all, white homeowners accelerated the division by moving away from downtown and into predominantly white suburbs — the same “white flight” that remade American cities from coast to coast after World War II.

You can see it all in Gordon’s maps, drawn meticulously from government records and Census data. Or you can read it more poetically in the charming prose of the late St. Louis writer Stanley Elkin. In his 1980 love song to St. Louis, first published in Esquire, he noted the peculiar boundaries of his chosen home:

“St. Louis … is a city of sealed neighborhoods, gated as a railroad crossing, of blocked-off streets and private places, chartered as a nation, zoned as meteorological maps, the enclaves and cul-de-sac of stalled weather.”

The shooting of Michael Brown, and the violence that followed, happened smack on one of those borders. Ferguson is an inner-ring suburb that is neither black nor white. Its southern border abuts a storied country club where Ben Hogan won the 1948 PGA Championship. Other parts of the little city-inside-a-city produce an overall unemployment rate of nearly 20%.

Established in 1894, Ferguson encompasses rough-around-the-edges manufactured homes and turn-of-the-century Victorian manors within its 6 sq. mi. It is a mixture of suburban and blue collar, home to “King of Kash” payday loan shops as well as boutique home-decor stores. One of Missouri’s largest corporations, Emerson Electric, has its headquarters there.

St. Louis rapper Tef Poe, writing in the Riverfront Times, caught the jagged feeling of the border city last year in his description of a neighborhood not far from Ferguson: “Rich people, middle-income, lower-income and dirt-poor people living blocks apart from each other in what is basically the same neighborhood.”

As the tension in Ferguson and nearby communities stretched into its fourth day, protesters seemed torn by the friction of a city built on such fine lines. “We’re not stupid! We’re not stupid!” a group of peaceful protesters chanted in the direction of a line of 130 county police in riot gear. Chanel Ruffin, 25, a Ferguson resident, said that “Ferguson police show us no respect. They harass black people all the time.” She said she knew Michael Brown, and “he was a nice guy. He was going to start college and make something of himself. He didn’t deserve to be shot so many times.”

Like others in the crowd, Ruffin did not try to explain the riot — much less to justify it. “I’m not saying what they did was right,” she said.

Things happen along these fault lines that cannot be entirely explained.

They can only be felt. “People were acting out of emotions,” Ruffin ventured. “There are a lot of people hurting.”

— With reporting by Kristina Sauerwein / Ferguson, Mo.

Witness Tension Between Police and Protestors in Ferguson, Mo.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com