Students in Texas have a question for their state lawmakers: Why us? In September, they’ll get to pose that question in court.

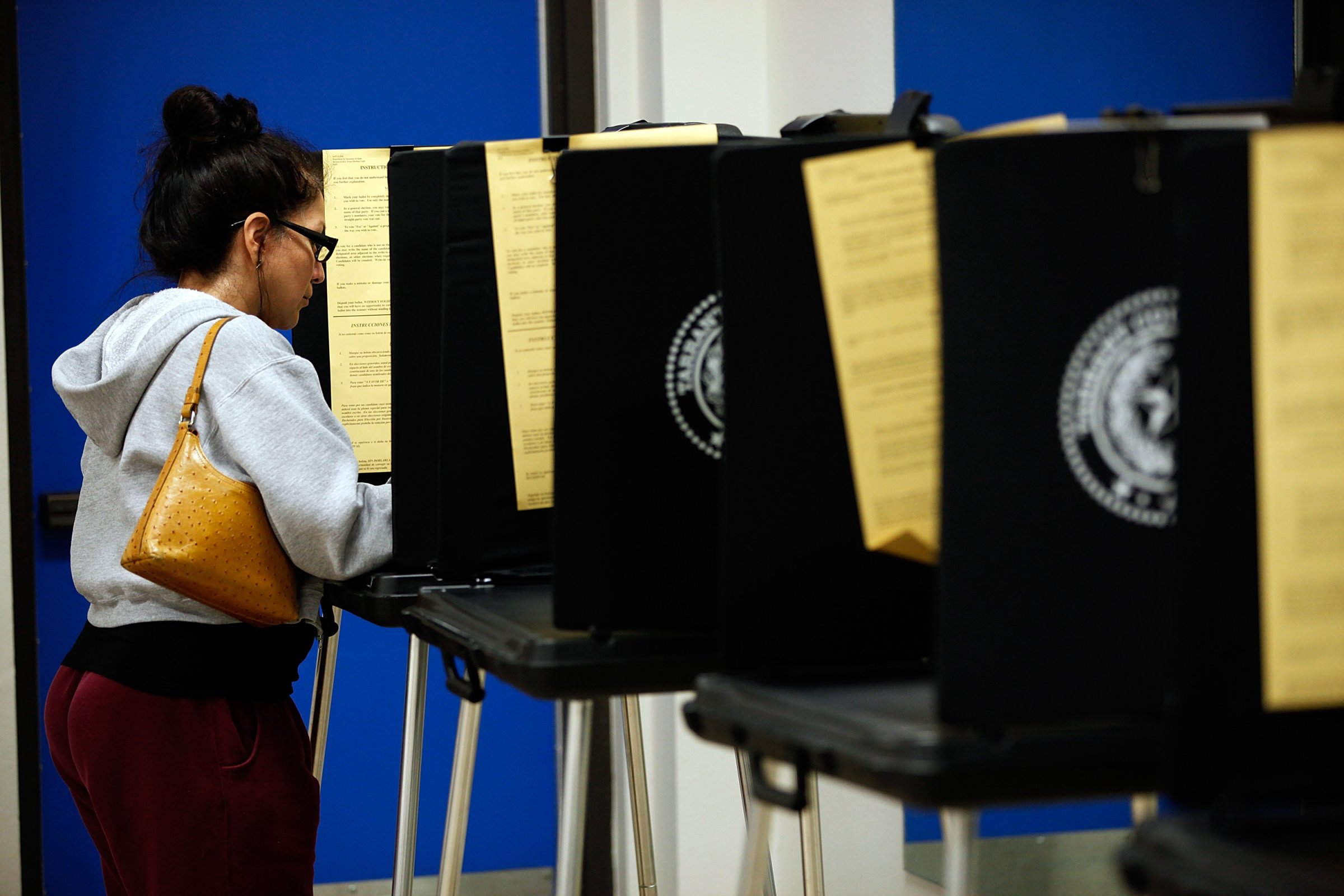

Over the last year, laws that advocates say place unnecessary burdens on voters have advanced across the country. But a law in Texas is causing a particular stir due to its potential to place the harshest burdens on the youngest voters. A lawsuit challenging it that was filed last year goes to trial Sept. 2.

“We work to engage people—young people—in this process,” said Christina Sanders, state director of the Texas League of Young Voters, which is among the plaintiffs in an upcoming voter identification case in the state. “The hurdles these laws create makes it more difficult for us to engage.”

“More than cases of apathy, it becomes a case of disenfranchisement,” she added.

For Sanders and the Texas League of Young Voters, the Supreme Court’s Shelby County v. Holder decision—which nullified key portions of the landmark Voting Rights Act—has given them a case of judicial déjà vu. The group’s first action after its founding in 2010 was joining in the initial challenge to the law that restricts the type of identification voters can use at Texas polls, a lawsuit that prevented the measure from taking effect in 2012. But because of the Supreme Court’s decision that invalidated the portion of the Voting Rights Act used to block the law, it was able to take hold almost immediately after the high court’s ruling. The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, on behalf of the League, joined the Department of Justice lawsuit last year in an effort to once again seek refuge from the law in the courts.

The state has said the ID requirement is an effort to prevent in-person voter fraud. In a 2013 editorial, Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott said requiring voters to present government issued IDs is “the first step in the process is to ensure that only those that are legally allowed to vote actually vote.” He called the efforts to block the law misguided, noting that some 83% of adults and 84% of registered voters support voter ID laws, according to a 2013 McClatchy-Marist poll.

“To those that oppose voter ID laws, how about instead of trying to incite racial violence and protests, you walk the walk and help those you believe to be poor or disenfranchised without photo ID to acquire a photo ID,” Abbott said.

Under the law, seven forms of identification are accepted at Texas polling stations, among them state drivers’ licenses and identification cards, election identification certificates, military IDs, passports, citizenship documents with photos, and concealed handgun licenses. And noticeably absent from that list: student identification cards.

In Texas, voter turnout for youth was among the lowest in 2012 at 29.6%, according to the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University. But voting rights advocates worry these laws will only further discourage young people from voting in the state. Between 600,000 and 800,000 voters may be ineligible to vote under the Texas law, many of whom may be students given the fact that nationally only about 65% of 18 year-olds have licenses, according to a 2011 University of Michigan study.

Ryan Haygood, director for the Legal Defense Fund’s political participation group, said student IDs were specifically left off the list because they fail to prove whether a student is a citizen or a resident, though he said there have been no instances of student non-citizens attempting to vote in person.

“There are two ways you can win an election, get more people to participate or get less of your opponents potential voters to participate,” Haygood said. “These laws prey on groups that have been historically marginalized.”

About 45% of eligible 18 to 29 year-olds voted during the 2012 presidential election, casting over 20 million votes, according to CIRCLE. That rate was a bit below the 51% mark from from 2008 but an overall boost compared to the 15 million cast in 2000.

Sanders said preventing students from using their state college IDs to vote causes “an extra hurdle,” and one many advocates don’t understand.

“We haven’t heard really good rationale for it,” said Dale Ho, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Voting Rights Project. While states have argued that because student IDs often do not have addresses they can’t verify residence, voter ID laws, Ho said, are justified not as a means of confirming residence, but a way to confirm identity.

“It doesn’t make any sense to exclude student IDs on the basis of an address,” he says. “It leads us to think the only reason why they’re excluding student IDs is that they don’t want students to vote.” Younger voters tend to vote disproportionately Democratic, and laws passed in Texas and elsewhere increasing restrictions on student IDs have been pushed by Republicans.

And the Lone Star state isn’t the only state where the student vote may be at risk. As the New York Times reported in July, students in North Carolina have filed a lawsuit saying the state’s restrictive voting measures, which also prohibit the use of state university IDs at the polls, violate the 26th Amendment—the one that says the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any sate on account of age.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com