Correction appended, Aug. 11, 2014

Almost 10 million Americans changed how they identify their race or ethnicity when asked by the Census Bureau over the course of a decade, according to a new study, adding further uncertainty to data officials already consider to be unreliable.

Using anonymized data for 162 million Americans who responded to census surveys in 2000 and 2010, researchers at the University of Minnesota and the Census Bureau concluded that self-identified race and ethnicity are fluid concepts for millions of Americans.

If the data set were nationally representative, researchers said, then the figure would translate to roughly 8% of Americans self-identifying differently over time. But such conclusions are difficult to draw: if a certain racial group, for example, responded less frequently to the 2010 Census than in 2000, that group would be underrepresented.

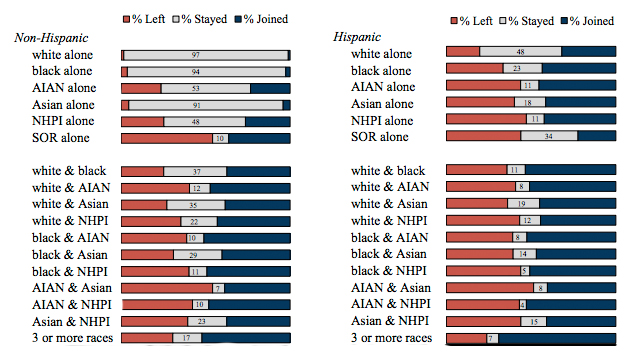

Researchers examining inconsistency in racial identification found that those who identified their ethnicity as Hispanic in 2000 were more likely to change their race in 2010. Only 48% of Hispanics who identified as white in 2000, for example, “stayed” white in 2010; the parallel statistic for non-Hispanic whites was 97%. Another group that appeared to alter racial identity more frequently was people who selected one of 10 biracial options in 2000, regardless of Hispanic origin.

The report’s findings complicate the Census Bureau’s multiyear research project to improve the reliability of its race and ethnicity data. The project, called the Alternative Questionnaire Experiment, focused on reducing the 6.2% of 2010 Census respondents who had selected “some other race.” And 6.2% isn’t insignificant: it translates to millions of Americans whose race or ethnicity data are essentially unknown to the U.S. government.

Race and ethnicity are becoming increasingly complex, researchers emphasized, and it’s becoming more and more difficult for Americans to classify themselves with the check of a box.

“If social science evidence is correct, people are constantly experiencing and negotiating their racial and ethnic identities in interactions with people and institutions, and in personal, local, national, and historical context,” the study said. “Perhaps it is not surprising that people change responses and instead it is surprising that so many are consistent in their race and Hispanic origin reports to the Census Bureau.”

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the proportion of Americans who would change their self-identified race or ethnicity over time if the study data were nationally representative (it is 8%) and the proportion of Hispanics who identified as white in 2000 who “stayed” white in 2010 (it is 48%).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com