Updated 6:58 a.m. E.T. on Aug. 6

An execution Wednesday in Missouri brought the state’s pace of executions near record levels, at a time when problems with lethal injections around the U.S. have led to growing scrutiny of the method.

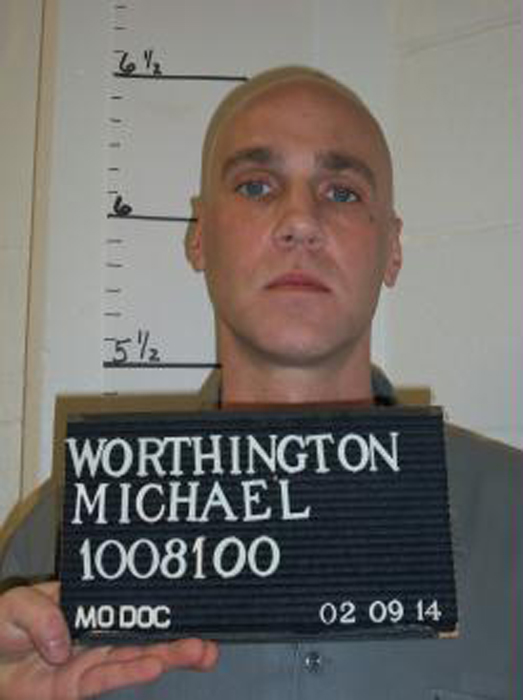

Death row inmate Michael Worthington was put to death early Wednesday, the first in the U.S. since the nearly two-hour-long execution of Joseph Wood in Arizona that again raised questions about the humaneness of lethal injections. It was the seventh this year for Missouri, the most since 2001.

The execution of Worthington—convicted in 1995 of murdering and raping a St. Louis woman—put Missouri alongside Texas and Florida, which lead the country in executions this year at seven each. The three states combined have now executed 21 of the 27 inmates put to death in 2014. The number of executions this year has been accelerated thanks to a combination of backlogged cases now making their way through the system, inmate appeals that have been exhausted in court, and conservative judicial appointments at the state and federal level.

“It’s kind of a perfect storm,” says Sean O’Brien, a University of Missouri-Kansas City law professor who studies capital punishment.

Missouri had already executed 76 inmates since 1976, the year the Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty, making it fifth among U.S. states behind Texas (511), Oklahoma (111), Virginia (110) and Florida (88).

The most inmates Missouri has executed in one year is nine in 1999. In 2001, it executed seven. But just a few years ago, executions in Missouri were rare. From 2006 to 2012, the state executed just two inmates as it struggled to obtain lethal injection drugs, partly because European pharmaceutical companies began restricting the sale of their products for use in capital punishment.

In May 2012, Missouri announced that it would switch to propofol, an anesthetic. It was the only state to do so, but Missouri never used it. Gov. Jay Nixon stopped the planned lethal injection of Allen Nicklasson in October after the European Union threatened to limit propofol’s export if it was used by prison systems in executions. Fresnius Kabi, a German-based pharmaceutical company, makes the drug—the same drug on which pop star Michael Jackson overdosed in 2009.

In October 2013, the state announced it would start using just one drug—the sedative pentobarbital, and the following month used it in the lethal injection of Joseph Franklin in November and Nicklasson in December. Earlier this year, the Missouri Times reported that the state department of corrections paid $11,000 in cash to obtain the drug from a compounding pharmacy, which is unregulated by the federal government.

Now that the state appears to have an adequate supply of pentobarbital, O’Brien says a backlog of cases is now moving through the system. And inmates’ constitutional challenges are finding little sympathy from federal courts.

“We’re seeing winning motions for requests for stays of execution at the trial level, but the Eighth Circuit vacates those routinely,” O’Brien says, referring to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit and adding that a number of conservative judges appointed by President George W. Bush often reverse lower court rulings.

Nixon, a Democrat and death penalty supporter, has also been unwilling to grant clemency in lethal injection cases, many of which the governor worked on as an attorney general for the state.

“He hasn’t ruled on a lot of the clemency petitions before him,” says Susan McGraugh, a St. Louis University law professor. “But the simple answer for why these executions are moving forward is because they can.”

Worthington’s attorneys were still working Tuesday to get a stay of execution through last-minute appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court, which has been largely unwilling to grant stays to death row inmates who argue that their executions shouldn’t go forward based on Eighth Amendment claims. Worthington’s lawyers were attempting to get a stay until a decision is reached in a case in front of the Eighth Circuit brought by Worthington and 14 other Missouri death row inmates who are challenging the secrecy of where the state obtains execution drugs while arguing that lethal injection violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. The court is scheduled to hear the case in early September.

Missouri has yet to be involved in a recent execution gone awry. One massive dose of a drug like pentobarbital has so far appeared to be a more effective way of administering lethal injection than a two-drug combination. The botched executions of Dennis McGuire in Ohio in January and Joseph Wood in Arizona in July both used a two-drug combination of midazolam and hydromorphone. But Kent Gipson, an attorney for Worthington, thinks that Missouri will join those states soon enough.

“It’s just a matter of time before something goes wrong in one of these in Missouri,” Gipson says. “There’s a bigger risk of it happening when it’s all under a veil of secrecy and from an unknown source that isn’t tested.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com