At one of Robert Altman’s Paris parties in the mid-’80s, Sally Kellerman says, “Bob, remember that shower scene in MASH where you made me get naked? You get naked.” And he does, the big bear in full rear and side nudity, exposing himself to the camera’s appraising eye with the same eager vulnerability he had demanded of his actors.

“Bob loved to throw a party,” Kathryn Reed, the director’s wife of 47 years, says in Altman (no scholarly subtitle), the engaging documentary feature that begins its run on the EPIX pay-movie channel Wednesday. His films were raucous parties, too: he would assemble crowds of actors, give them the hint of a story, encourage them to improvise in Babels of overlapping dialogue and let the canny chaos spill onto the screen. That tactic applied from Altman’s first signature effort, MASH in 1970, when he was already 44, to A Prairie Home Companion, released just before his death at 81 in 2006, and with Nashville, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, A Wedding, HealtH, Popeye, The Player, Short Cuts, Prêt-à-Porter and Gosford Park in between.

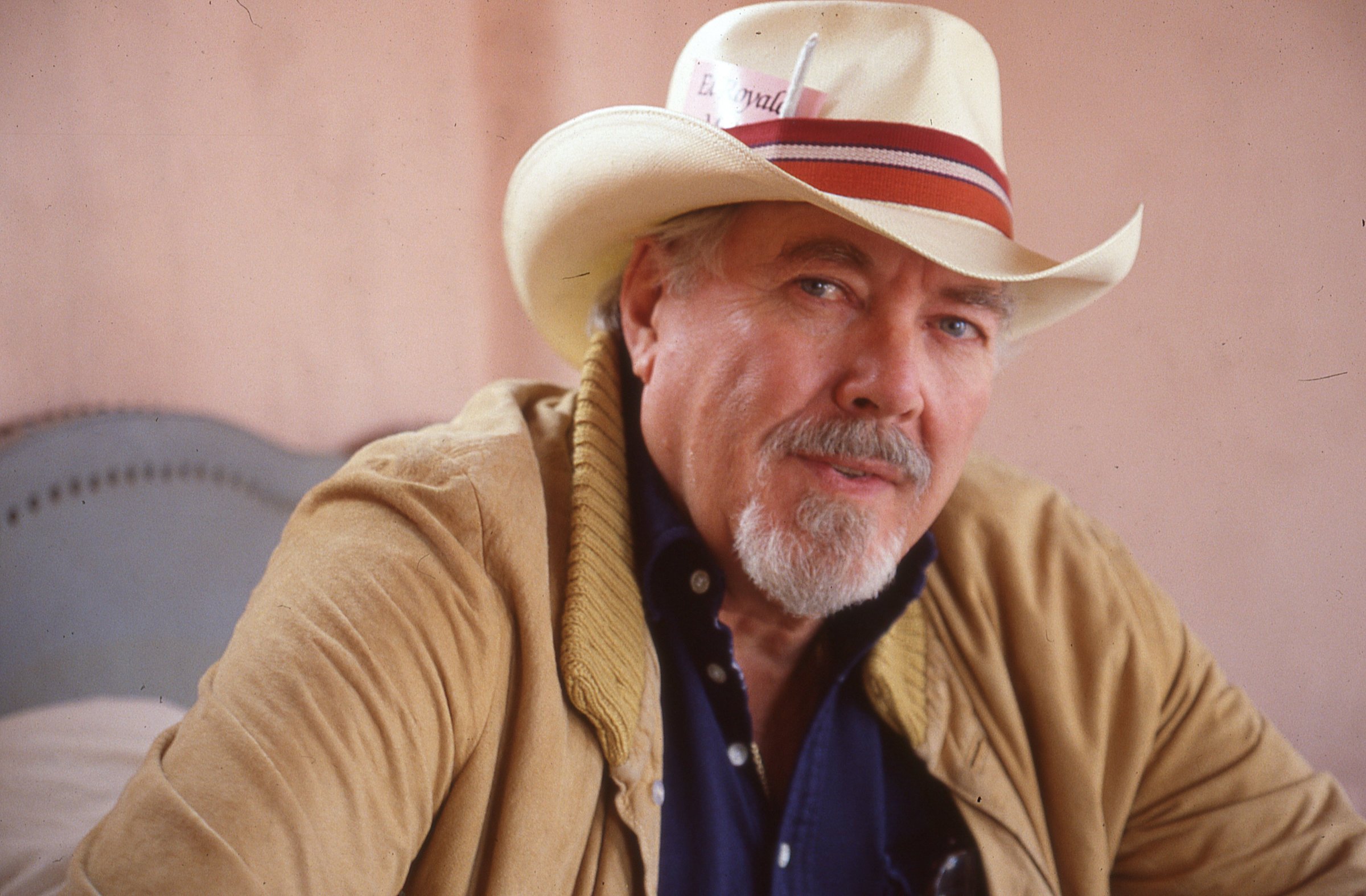

Produced and directed by Ron Mann (whose doc résumé includes Comic Book Confidential) and written by Len Blum (who worked on the scripts for Meatballs, Stripes and the Howard Stern Private Parts), the EPIX Altman is a generous take on a complicated personality. Mann convenes an all-star cast — Kellerman, Meryl Streep, Lily Tomlin, Bruce Willis, Robin Williams, Julianne Moore, Elliott Gould, James Caan, Keith Carradine, Michael Murphy, Lyle Lovett, Philip Baker Hall — to remember the good times and underline Altman’s unique contributions to a bracingly unruly period in American film. Boasting a trove of rare clips from the director’s early work, his location footage, interviews and home movies (including the naked-Bob scene), Mann’s Altman has qualities rarely found in an Altman film: clarity, cohesion and heart.

(READ: Corliss’s 2006 remembrance of Robert Altman)

Born in Kansas City in 1925, Bob Altman served on bomber crews in World War II and went to Hollywood, where he amassed one story credit on the 1948 B movie The Bodyguard. Returning to his home town, he made instructional films (How to Run a Filling Station, Better Football) and a troubled-teen drama, The Delinquents, which got him back to Hollywood directing TV shows. On one of these he met his future wife. As Kathryn recalls, “He looked a little hung over. He didn’t say hello. He said, ‘How are your morals?’ I said, ‘A little shaky, how are yours?’” It was the beginning of a love affair that, at least from her side, still hasn’t ended.

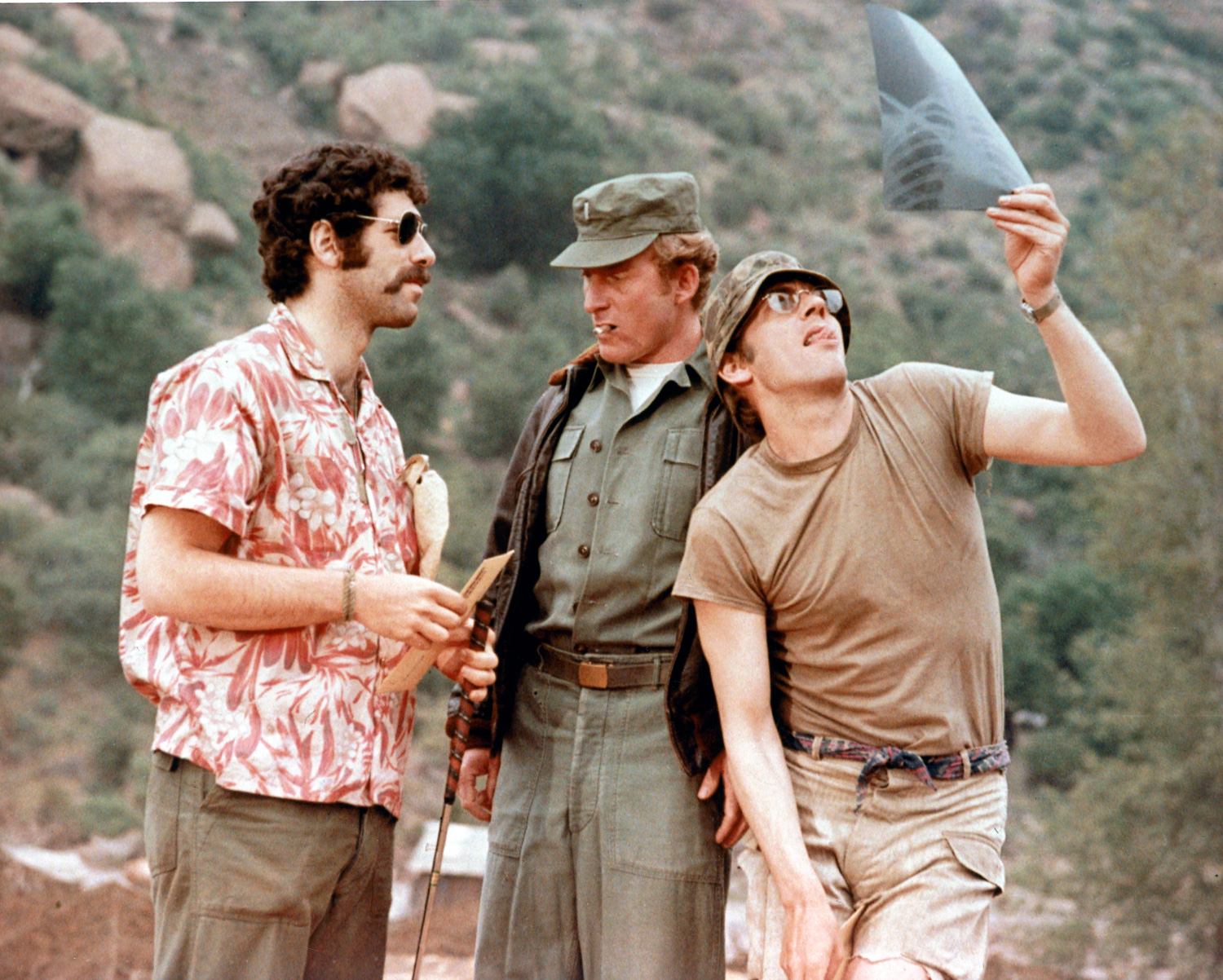

Fired off his first Hollywood feature, Countdown, after studio chief Jack Warner fumed, “That fool has actors talking at the same time,” Altman found his ticket to independence with Ring Lardner Jr.’s script for MASH, to which more than a dozen directors had already said no. A gigantic, surprise hit, the movie earned $81.6 million in 1970, which in today’s dollars, according to Box Office Mojo, would be $437.5 million, or more than the domestic revenue for Frozen or any Marvel movie except The Avengers. That box-office cachet enabled Altman to line up smaller, weirder projects — a protean 15 features released between early 1970 and late 1980 — from the signature party movies to claustrophobic fantasies like Images, 3 Women and Quintet. Newbies to the Altman canon should check out McCabe & Mrs. Miller, a druggy Western with Warren Beatty and Julie Christie, and Nashville, an indictment of the country-music ethos as a microcosm of Nixon-driven, assassination-prone America.

An ornery renegade like Altman could become a mainstream film force only in the 1970s, when, he says, “the studios turned filmmaking back to the artists. So I got to do a lot of stuff that was not the formula that had existed before.” Some directors took their cues from European masters like Fellini and Bergman, but an Altman film was all-American: teeming and loose-limbed, with a political subtext and a tone that could be called either trenchant or snide. (In a Q&A session from the new doc, Altman deflects charges of his cynicism by saying, “I just try to show what I see. If it’s ugly, that’s what I see.”) In a sense, Altman radically democratized movies, upending the Hollywood hierarchy of star over supporting player, story over atmosphere, emotion over all. Viewers of an Altman movie had to decide what was important by what they could catch from all the milling and chatting; they voted with their eyes and ears.

(READ: Kurt Andersen on the ups and downs of Robert Altman’s career)

The last film of Altman’s golden decade was Popeye, which parlayed Robin Williams’ TV éclat into a $50-million domestic gross (about $150 million today), Plagued by bad weather and cost overruns, Popeye left a sour taste in everyone’s mouth and made Altman unemployable in Hollywood. “The films the major companies want to make now are films I don’t want to make, also I can’t make,” he said at the time. “And the films I do want to make, and feel that I can make, they don’t want to make.” In another interview, he put it this way: “I make gloves, and they sell shoes.”

Banished but unbowed, he moved to New York and then Paris, and managed another dozen films in the ’80s, often adaptations of plays, plus the pioneering HBO show Tanner ’88, conceived by Garry Trudeau and thrusting fake Presidential candidate Michael Murphy into the real campaigns of other candidates. The Player, in 1992, finally brought Altman back to Hollywood with a clever poison-pen letter to the studios that had dumped him. “It’s a very, very mild indictment” of the movie industry, he said. “Things aren’t really like that. They’re much worse.”

(READ: Corliss’s review of The Player)

The movie goes heavy on the inspiration and innovation (the prowling camera, the radio mikes to record each actor’s dialogue) and light on Altman’s fondness for gambling, dope and booze. In the bio-doc, one TV interviewer asks Altman if he ever bet $10,000 on a football game. “Uh-huh.” And how is your stake? “I’m behind.” In a Los Angeles Times review of an Altman oral history in 2009, TIME’s Richard Schickel wrote: “It appears that from the beginning of his career until almost its end (when illness slowed him), Robert Altman never passed an entirely sober day in his life, “When he was not drinking heavily, he was smoking dope — often doing both simultaneously.” In his seventies, after suffering a ministroke, Altman finally swore off spirits, telling Kathryn, “The only thing I miss about drinking is the alcohol.”

(READ: Richard Schickel on the legacy of Robert Altman)

The filmmaker had his prickly side. He loved actors, while deriding many of the studio bosses who financed his work and dismissing the contributions of his films’ writers. (Please note that some of his most popular or memorable achievements came from distinguished screenwriters: Lardner on MASH, Leigh Brackett on The Long Goodbye, Jules Feiffer on Popeye, Trudeau on Tanner ’88, Michael Tolkin on The Player and Julian Fellowes on Gosford Park.) He could also hold venerable grudges against critics who occasionally lapsed in their support for him. More than 20 years after I wrote a mixed-negative review of MASH in the New York Times, he corralled TIME show-business reporter Jeff Ressner at Cannes and said of me, “Isn’t he dead yet?” This director of acerbic film statements was quick to take offense — the iron fist encased in thin skin.

How distant those skirmishes seem, in a movie decade when blockbusters rule, critics have no box-office relevance and most indie films are far less adventurous than any of a dozen Altman movies. In retrospect, one is tempted to think as fondly, as benignly, of Robert Altman as Mann’s documentary does. Narrated in large and appealing part by Kathryn and her children, the film is as intimate as it is admiring, for this home movie focuses on Altman the husband and father.

While his kids grew up, Dad was often off making movies, as far as possible from studio interference. But later he brought them into his filmmaking clan: Stephen a production designer, Robert Reed a camera operator. And toward the end, Michael Altman recalls, “He became very enamored of his family. … We would have these get-togethers, and I would catch him sitting in the corner just looking at everybody, with that grin on his face. It was like one of his movies — like he became aware he was in his own movie. And he’d loved the cast.”

This week, EPIX is throwing another Bob Altman party. The least we can do if offer the crafty old renegade a teetotaler’s toast.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com