You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. For access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

Wherefore Richard M. Nixon, by such conduct, warrants impeachment and trial, and removal from office.

After four garrulous days, the talking stopped. The room was silent, and so, in a sense, was a watching nation. One by one, the strained and solemn faces of the 38 members of the House Judiciary Committee were focused on by the television cameras. One by one, their names were called. One by one, they cast the most momentous vote of their political lives, or of any representative of the American people in a century.

Mr. Railsback. Aye. Mr. Fish. Aye. Mr. Hogan. Aye. Mr. Butler. Aye. Mr. Cohen. Aye. Mr. Froehlich. Aye.

Thus six Republican Congressmen joined all 21 Democrats to recommend that the House of Representatives impeach Richard M. Nixon and seek his removal from the presidency through a Senate trial. And thus the Judiciary Committee climaxed seven months of agonizing inquiry into the conduct of Richard Nixon as President by approving an article of impeachment that charges he violated both his oath to protect the Constitution and his duty to take care that the laws be faithfully executed. The first of at least two articles to be considered, the article alleges that he committed multiple acts designed to obstruct justice in his attempt to conceal the origins of the June 1972 wiretap-burglary of Democratic National Headquarters and “other unlawful covert activities” carried out by those responsible for that crime (see text on page 12).

By that historic roll-call vote, the article of impeachment was adopted, 27 to 11, by the committee at 7:07 p.m. on a warm Saturday night in Room 2141 of Washington’s Rayburn Office Building. Richard Nixon became only the second President to stand so accused by a committee of Congress. The impressive bipartisan nature of the vote increased the probability that the full House of Representatives will also vote to impeach.

The impeachment action came at the end of a week in which the President’s chances of completing his second term in office fell to their lowest point since the Watergate scandal first threatened his political survival. Earlier in the week, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that Nixon had no authority to withhold tape recordings of his White House conversations from Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski (see page 20). The ruling raised the possibility that more evidence damaging to the President may become available.

The degree of bipartisanship in the Judiciary Committee vote was larger than had been expected, and it effectively rebutted the increasingly shrill claims from White House officials that the impeachment inquiry was a highly partisan “witch hunt” and that the committee amounted to “a kangaroo court.” The range of Republican support for impeachment, embracing the Midwest’s Harold Froehlich and Tom Railsback, the South’s M. Caldwell Butler, the East’s Hamilton Fish and New England’s William Cohen, may well influence wavering Republicans when the full House acts on the committee’s recommendation. The influential roles played in the committee’s decision to impeach by its articulate Southern Democrats, Alabama’s Walter Flowers, South Carolina’s James Mann and Arkansas’ Ray Thornton may also swing other Southern Congressmen against the President.

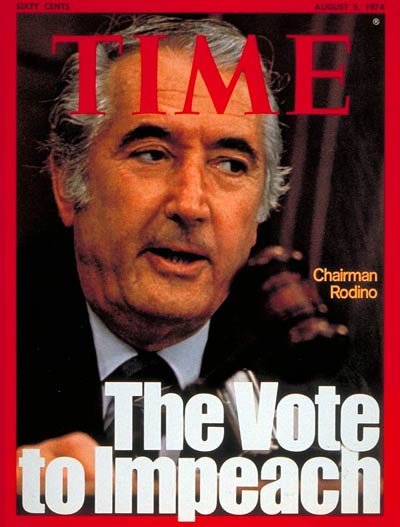

Although the committee’s final public deliberation sometimes drifted into partisan bickering and time-consuming parliamentary gamesmanship, the result vindicated the patience and pace of the committee’s determined chairman Peter Rodino. Through some seven months of laborious study, he kept the committee’s overworked staff and its philosophically and temperamentally diverse members driving toward a resolution of its agonizing dilemma. When his committee faced its final act of judgment, the country was treated to a surprise: a group of nationally obscure and generally underrated Congressmen and Congresswomen rose to the occasion. Often with eloquence and poise, they faced the television cameras and demonstrated their mastery of complex detail, their dedication to duty, and their conscientious search for solutions that would best serve the public interest.

Rodino had long since been thoroughly convinced that impeachment was warranted by the committee’s vast accumulation of evidence that was presented by Special Counsel John Doar and Minority Counsel Albert Tenner through eleven weeks of closed hearings and laid out in 36 notebooks of “statements of information.” Rodino had one main aim as the days of decision approached: to secure maximum committee support for any articles of impeachment that would be recommended to the House. He knew that there was no hope of enlisting about ten Republicans firmly committed to Nixon’s defense, but he hoped that articles could be drawn in a way that would attract the remaining Republicans, all troubled by some of Nixon’s Watergate-related actions. Yet he also had the problem of not limiting the charges against the President so narrowly that the more liberal Democrats would insist on toughening the language or adding more articles. Rodino was worried too about some of the Southern Democrats, whose home districts tend to favor Nixon heavily.

Rodino and some House Democratic leaders then moved adroitly to seek the help of the Southern Democrats on the committee. These men, Flowers, Mann and Thornton, were offended by Nixon’s encroachment on the Constitution and on such agencies as the FBI and IRS. They also are persuasive, soft-sell politicians with an ability to find common cause with the undecided Republicans. The key to gaining maximum support for articles, one House leader explained, was “to put together the Southern Democrats and the Republicans.” The way to do that, this veteran told Rodino, was “to get Walter Flowers.”

Well aware that his state of Alabama had long liked Nixon, Flowers seemed the most likely Democrat to vote against impeachment. He had developed an ulcer over the problem. Gently, Rodino urged Flowers to seek meetings with the moderate Republicans to see if they might find areas of agreement. The chairman asked the articulate and diplomatic Mann to do the same thing. By Tuesday, private meetings had begun among three Southerners and four uncommitted Republicans: Railsback, Cohen, Butler and Fish. This centrist group stood between the all-out impeachers and the Nixon loyalists.

Another Southern Democrat, Jack Brooks of Texas, also played a shrewd backstage role as the committee struggled for consensus. A persistent Nixon critic, Brooks prepared and distributed to all members of the committee a sweeping series of articles of impeachment that were poorly drawn and too strong for most of the undecided members. But the articles had their intended effect; many members reacted against the Brooks proposals and began working on alternative drafts of their own. As one staff leader later explained, “That got the members thinking. They also began to wake up to the fact that they shouldn’t leave it to Doar and the staff.”

The general domination of the staff work by Doar was resented by some veteran committee members. They felt that their regular counsel, Jerome Zeifman, a 49-year-old Democratic liberal, had been shunted aside by Doar, who had been recruited from the outside. Seeking advice and help from Zeifman, many of the majority Democrats began framing articles of their own as alternatives to those presented by Doar and those of Brooks. Rodino purposely refrained from taking part in the drafting sessions but kept in touch with all of them. He saw his role as a coordinator who would be more effective if he did not become identified with specific draft proposals.

Soon two overlapping groups were working on articles: 1) a partial Democratic caucus, heavily influenced by Brooks but not dominated by him, and 2) the coalition of Southern Democrats and impeachment-leaning Republicans. The Southerners were able to shuttle between the two groups and thus were especially influential. Surprisingly, the coalition group moved more quickly toward agreement than the all-Democratic drafters. By the end of Tuesday, said one of the coalition Congressmen, “we had unanimity, a consensus, in two major areas: the abuse of power and the obstruction of justice.” It was then clear that at least four Republicans — Railsback, Cohen, Butler and Fish — would go for impeachment.

How Private Decisions Were Made

In this seven-member coalition, the thinking of Southern Democrat and Northern Republican had much in common. “I had a yearning, an innate desire to find the President innocent,” recalled Walter Flowers. “I put the blinders on like the old mule used to wear going down the road with the wagon behind him. I couldn’t see anything ahead except the road.” He was particularly troubled by the March 21, 1973 tape, not merely the celebrated “For Christ’s sake, get it” quote, but rather, as Flowers put it, “the matter-of-fact way in which the payment of hush money was discussed. It shocked my conscience, I’ll tell you.”

He was also disturbed by the discrepancy between what the President was doing and what he was saying. “You take the whole sordid mess and compare it to the public pronouncements of the President, and it just doesn’t fit.” He talked often with Ray Thorn ton and James Mann, sometimes as they walked together to the House floor, and finally decided. “I felt that if we didn’t impeach, we’d just ingrain and stamp in our highest office a standard of conduct that’s just unacceptable.”

Flowers in turn was an important influence on the Republicans in the group. At a Sunday meeting, he told the undecided seven, “This is something we just cannot walk away from. It happened, and now we’ve got to deal with it.” Recalled Caldwell Butler later: “I knew at that second he was right.” Butler, whose Virginia district is heavily pro-Nixon, made his decision soon after a visit to his district by Vice President Gerald Ford, who assured the voters that he would support Butler for re-election this fall no matter how he voted on impeachment.

Suddenly, a fifth Republican, who had remained aloof from the others and kept his intention quiet, broke away from Nixon.

Lawrence Hogan did so publicly in a harsh statement against the President that dismayed party loyalists on the committee and undoubtedly had a psychological impact on the undecideds. “The evidence convinces me that my President has lied repeatedly,” Hogan said at a press conference, “deceiving public officials and the American people. Instead of cooperating with prosecutors and investigators, as he said publicly, he concealed and covered up evidence, and coached witnesses so that their testimony would show things that really were not true… he praised and rewarded those who he knew had committed perjury. He actively participated in an extended and extensive conspiracy to obstruct justice.” A conservative seeking the governorship of Maryland, Hogan frankly conceded that he spoke out early so that his views would not be lost in the committee’s 38-member debate. His later, strong arguments in that debate left little doubt of his sincerity in urging impeachment, even though his act probably was a political plus in Maryland.

Describing how he reached his decision, Hogan recalled that he began listening to the evidence with a “firm presumption” that the President was innocent. “But after reading the transcripts,” he said, “it was sobering: the number of untruths, the deception and the immoral attitudes. At that point, I began tilting against the President, and my conviction grew steadily.”

While driving home one evening a week ago, he suddenly realized that he had made up his mind to vote for impeachment. “There was just too much evidence,” he remarked later. “By any standard of proof demanded, we had to bind him over for trial and removal by the Senate.” When he got home, he told his wife of his decision. “She said, ‘Good,'” Hogan reported, “the first direct political advice she’s ever offered.”

The Anguish of Responsibility

On Wednesday, in their private drafting sessions, the two groups of pro-impeachment forces began coalescing. The Democratic group was reaching agreement on the same two general articles as the coalition negotiators had decided on: obstruction of justice and abuse of power. As the formal opening of the televised Judiciary Committee meetings approached, however, the Democratic group had not completed its drafting work. Its members still wondered whether there should be a third article charging Nixon with contempt of Congress for ignoring the committee’s subpoenas. Two articles were hastily sketched out, mainly by South Carolina’s Mann. “A lot of the real nuts and bolts were put together by Mann,” said one participant. The coalition group, also heavily influenced by Mann, had its similar proposals ready. Actually, the unperfected Democratic proposals were the ones later introduced by Harold Donohue of Massachusetts as the takeoff points for the extended debate.

The public moment of truth arrived as Chairman Rodino banged his gavel in the Judiciary Committee’s draped and paneled room at 7:44 p.m. on Wednesday. Quickly the Congressmen and Congresswomen dispelled any fears of their Capitol Hill colleagues that they might disgrace the national legislature in this first televised debate and decision of a congressional committee. The tone of solemnity and historic significance was established by the chairman.

“Throughout all of the painstaking proceedings of this committee,” said Rodino in his thin voice, “I as the chairman have been guided by a simple principle, the principle that the law must deal fairly with every man. For me, this is the oldest principle of democracy. It is this simple but great principle which enables man to live justly and in decency in a free society … Make no mistake about it. This is a turning point whatever we decide. Our judgment is not concerned with an individual but with a system of constitutional government… Whatever we now decide, we must have the integrity and the decency, the will and the courage to decide rightly. Let us leave the Constitution as unimpaired for our children as our predecessors left it to us.”

In opening statements ranging up to 15 minutes, the members one after another expressed their individual anguish over the decision they faced. Burdened by the problem of party loyalty, the Republicans suffered most. Declared Cohen: “I have been faced with the terrible responsibility of assessing the conduct of a President that I voted for, believed to be the best man to lead this country, who has made significant and lasting contributions toward securing peace in this country, throughout the world, but a President who in the process by actor acquiescence allowed the rule of law and the Constitution to slip under the boots of indifference and arrogance and abuse.”

“How distasteful this proceeding is for me,” protested Virginia’s assertively fast-talking Butler, explaining that he had worked with Nixon in every one of the President’s national elections, “and I would not be here today if it were not for our joint effort in 1972.” Wistfully, Illinois’ troubled and emotional Railsback sought escape. “I wish the President could do something to absolve himself,” he said. Even New Jersey’s Charles Sandman abandoned his brawling manner to explain: “For the first time in my life I have to judge a Republican, a man who holds the most powerful office in the world … This is the most important thing I shall ever do in my whole life, and I know it.”

To New York Democrat Charles Rangel, the occasion had a positive side. “Some say this is a sad day in America’s history,” he said. “I think it could perhaps be one of our brightest days. It could be really a test of the strength of our Constitution, because what I think it means to most Americans is that when this or any other President violates his sacred oath of office, the people are not left helpless.”

Although some tried to keep their opening statements neutral, most revealed their position on impeachment right off, and at first there were few surprises. Wisconsin’s Democrat Robert Kastenmeier contended that “President Nixon’s conduct in office is a case history of the abuse of presidential power.” New York Democrat Elizabeth Holtzman detected “a seamless web of misconduct so serious that it leaves me shaken.” Texan Brooks claimed that the committee evidence traced “governmental corruption unequaled in the history of the United States.” Asked Republican Cohen: “How in the world did we ever get from the Federalist papers to the edited transcripts?”

In the view of many members of the committee’s majority, failure to impeach would do far greater harm to the nation’s welfare than would the trauma of a Senate trial. Surprising his colleagues with the vehemence of his anti-Nixon stand, Republican Butler declared: “If we fail to impeach, we will have condoned and left unpunished a course of conduct totally inconsistent with the reasonable expectations of the American people … and we will have said to the American people, ‘These deeds are inconsequential and unimportant.’ ”

Democrat Thornton claimed that such a failure “would effectively repeal the right of this body to act as a check on the abuses that we see.” After breathlessly reeling off a lengthy list of specific improper Nixon acts, Rattsback warned of another result. Speaking of the nation’s young people, he claimed: “You are going to see the most frustrated people, the most turned-off people, the most disillusioned people, and it is going to make the period of L.B.J. in 1968,1967 … look tame.”

The President’s Staunchest Defenders

“To become Congressmen and Congresswomen,” noted Missouri Democrat William Hungate, “we took the same oath to uphold the Constitution which Richard M. Nixon took. If we are to be faithful to our oaths, we must find him faithless in his.” Iowa Democrat Edward Mezvinsky expressed a similar thought, arguing that Nixon should be brought “to account for the gross abuse of office,” and that “we must all ask ourselves, if we do not, who will?”

The President’s staunches! defenders quickly proved to be Sandman, California’s Charles Wiggins and Indiana’s David Dennis. Sandman called the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson in 1868 “one of the darkest moments in the Government of this great nation,” and added: “I do not propose to be any part of a second blotch on the history of this great nation.”

Nixon’s supporters chose mainly to attack the nature of the evidence on which the committee majority had based articles of impeachment. “This case must be decided according to the law, and on no other basis,” noted Wiggins. Posing sharp legalistic questions, Wiggins insisted that perhaps only half of one volume among the committee’s books of evidence would be admissible in a Senate trial of the President. “Simple theories, of course, are inadequate. That is not evidence. A supposition, however persuasive, is not evidence. A bare possibility that something might have happened is not evidence.”

To follow an evidentiary trail from the improper activities of Nixon’s aides to the President, argued California Republican Carlos Moorhead, “there is a big moat that you have to jump across to get the President involved — and I cannot jump over that moat.” Mississippi Republican Trent Lott argued with vigor that “for every bit of evidence implicating the President, there is evidence to the contrary.” The case against Nixon, contended Iowa 3 Republican Wiley Mayne, consists of “a series of inferences piled upon other inferences.”

In rapid-fire rebuttal, many of the committee Democrats in their turn rattled off specific presidential acts and conversations, particularly from the President’s tapes, that they considered solid evidence. But the most effective general reply was offered by Republican Cohen. “Conspiracies are not born in the sunlight of direct observations,” he said. “They are hatched in dark recesses, amid whispers and code words and verbal signals, and many times the footprints of guilt must be traced with a search light of probability, of common experience.” Moreover, circumstantial evidence is admissible in trials, Cohen noted, and it is often persuasive. He cited as an example that someone who had gone to sleep at night when the ground was bare and awoke to find snow on the ground could reasonably conclude that snow had fallen while he slept.

The Pro-Impeachment Republicans

Some members used then— opening statements to make impassioned pleas for articles of impeachment that seemed un likely to win support from a majority of their colleagues. Father Robert Drinan, a Massachusetts Democrat, argued that it was wrong not to cite Nixon for the secret bombing of Cambodia just because it would not “fly” or “play in Peoria.” Asked Drinan: “How can we impeach the President for concealing a burglary but not for concealing a massive bombing?” Surprisingly, New York Republican Henry Smith, considered wholly against impeachment, indicated that the Cambodia bombing was the one Nixon offense that he might consider impeachable. Mezvinsky urged that Nixon be cited for income tax evasion.

Running through Wednesday night and most of Thursday, the opening statements publicly confirmed Republican defections from the President that had become apparent in the closed-door strategy sessions on the eve of the debate. Demonstrating a willingness to impeach on at least one mainstream article were Illinois’ Robert McClory, Railsback, Fish, Butler and Cohen. In a speech that was at first tantalizingly noncommittal, Froehlich hinted that he might go along with an article on the obstruction of justice in the Watergate coverup.

Hogan followed his previous attack on Nixon with another assault. When Nixon and his aides discussed Watergate Burglar E. Howard Hunt’s demands for money in the celebrated March 21, 1973, White House conversation, Hogan protested: “The President didn’t, in righteous indignation, rise up and say, ‘Get out of here. You are in the office of the President of the United States. How can you talk about blackmail and bribery and keeping witnesses silent?’ . . . And then throw them out of his office and pick up the phone and call the Department of Justice and tell them there is obstruction of justice going on. But my President didn’t do that. He sat there, and he worked and worked to try to cover this thing up so it wouldn’t come to light.”

Most of the pro-impeachment Republicans seemed to feel that the voters would stand by them. Hogan reported that as of last Friday his telephone calls from Marylanders were running 1,072 to 634 in favor of his decision. Butler’s early mail ran about 50-50, but he also received vicious and obscene hate calls at his Roanoke home, upsetting his wife June. At week’s end Butler requested an unlisted telephone number, but he was not backing down. “If it’s come to that,” he muttered, “maybe we’re impeaching the man too late. My God, these people will have a chance within six months to express their opinion of my performance in office. This type of activity is totally beyond me.”

Still not satisfied with the quickly prepared articles of impeachment introduced under Donohue’s name, the impeachment forces went to work on new drafts as soon as the round of general debate was concluded on Thursday night. At this critical stage, Chairman Rodino joined the group of key Democrats assembled in Counsel Zeifman’s office. Among them were Flowers and Mann, who now held the virtual proxy votes of moderate Republicans. Their aim was to find precisely the right language that would placate the more liberal Democrats, hold the Southerners as well as the available Republicans, and yet be technically proficient enough to withstand the anticipated assault from the Nixon loyalists during the closing debate.

The drafting was resumed Friday morning, delaying the start of that day’s public session until 11:55. Finally, with little substantive change but a tightening and polishing of wording, the articles were introduced as an amendment to the Donohue articles by Maryland Democrat Paul Sarbanes, a precise, slow-speaking Rhodes scholar.

Before acting on the amendment, however, the legislators debated two time-consuming diversionary problems in a somewhat quarrelsome and highly repetitive lawyerly argument. At one point, Rodino tried to reduce each member’s debating time from five minutes to two minutes, but objections were raised. He then retained his evenhanded treatment of the contending parties, letting the debate drone on.

But if the words were sometimes weak, the images and personalities of the committee were vividly etched on a viewer’s consciousness as the proceedings continued. The TV cameras enabled Americans for the first tune to see for themselves just how representative this remarkably diverse group of U.S. Representatives really is. With few exceptions, they seemed less a group of politicians or lawyers (which all are) than a particularly well-cut cross-section of ordinary Americans, exposing the accents, the attitudes, the argot of the regions from which they come, and the universal Chaucerian splay of individual character.

There was Rangel, with big-city bluntness inviting his adversaries “to walk down this street” of evidence with him for a way. There was Thornton, speaking simply and sparingly with the unmistakable sincerity of his Arkansas folk. “It is amazing,” Sandman boomed in a kind of McCarthyesque excess of sarcasm and leering, as he hacked at some pro-impeachment speaker’s folly. Then came the patient, adenoidal, invariably intelligent queries of Wiggins, forever asking how the evidence touched the President. Or the schoolmasterly, quick thrusts of Dennis, clipping words and arguments.

The Deep Southerners, Flowers and Trent Lott, though on opposite sides, spoke with the easy fluidity and courtesy of their heritage. Mezvinsky was the new boy, carefully following the mood and model of his elders, Cohen the engagingly gawky bright boy of the class. Missouri’s Hungate, full of sometimes slightly hokey Ozark folklore, designated himself the comic, just as California’s Jerome Waldie attempted wry wit. Texas Democrat Bar bara Jordan loomed and boomed like some elemental force, her cultivated accent and erudition surprising each time she spoke.

If there seemed a kind of fastidious smirkiness in Delbert Latta, then by contrast Fish and Mayne, Kastenmeier and Mann exuded a quiet and impressive earnestness and integrity. (Kastenmeier displayed probably the most imposing arched eyebrows since John Barrymore’s.) For all their differences, the commit tee members clearly seemed to share the camaraderie of ship mates on an awesome voyage that none had chosen but all must take, to whatever end.

How Specific Must an Article Be?

In the general debate, the first sidetracking stemmed from an attempt by Republican McClory to delay proceedings for ten days if the President would promptly agree to give the House Judiciary Committee the same tapes he had been ordered by the Supreme Court to yield to Federal Judge John J. Sirica for use by Special Prosecutor Jaworski in the impending Watergate cover-up trial. Actually, McClory conceded that he had little expectation of a favorable response from Nixon. McClory’s tactic was aimed at strengthening a contempt of Congress article against the President he planned to introduce. The motion was defeated 27 to 11 in the first rough test of the committee’s voting lineup.

As direct debate on the Sarbanes amendment got under way, the committee fell into a second argument over just how specific or general the articles of impeachment ought to be. The Nixon loyalists, sometimes joined by more moderate Republicans, insisted that the proposed articles were much too vaguely phrased.

Democratic defenders of the articles contended that the supporting facts should — and would — be included in the committee’s final report and not jammed into the brief impeachment articles. The spirited argument had some light moments. Insisting that inferences can always be drawn from any given fact, Hungate suggested that “if someone brought an elephant through that door and I said ‘That’s an elephant,’ someone would say, ‘That’s an inference. It could be a mouse with a glandular condition.’ ” There were sharp personal exchanges as the commit tee grew restive. Latta irrelevantly criticized Counsel Jenner for having publicly supported the repeal of antiprostitution legislation, and Latta in turn was scolded by Ohio Democrat John Seiberling for his improper remarks.

The opposing viewpoints on specificity were best expressed by Sandman and Jordan. Growled Sandman: “Why, even a simple parking ticket has to be specific … yet you want to replace that [requirement] and say it doesn’t apply to the President.

Why, that’s ridiculous!”

Jordan (referred to as “the gentlelady” by Rodino) noted that the President was not being deprived of any information or due process. His lawyer James St. Clair had been permitted to sit through all the committee hearings on the evidence, receive all the documents given committee members, and cross-examine witnesses. “That was due process,” she said. “Due process tripled, due process quadrupled.” The Nixon loyalists, she charged, were using “phantom arguments, bottomless arguments.”

The proponents of more specific articles had a plausible argument in wishing the charges to be as clear as possible, both out of fairness to the President and a desire to make the task of the House easier in judging the articles. Yet the nature of the charges against the President is not confined to single acts but often embraces a course of conduct over a span of time involving many acts. To be specific would produce lengthy and complex articles. The framers of the articles, moreover, did not want to be confined too strictly to each specific claim, since that would limit the evidence that could eventually be used in the Senate.

The specifics would be spelled out in the committee’s report.

The long hours consumed in the dispute were turned into a prime-time display of partisan maneuvering. The Nixon sup porters sought to delay a final vote, hoping to discredit and dis courage the majority, perhaps even win back one or two of their strayed Republicans. Since the loyalists were demanding facts, many Democrats used their turn at the microphones to spin out the litany, as they saw it, of Nixon’s misdeeds. Most able of all at this was California’s Waldie, whose sporadic running narrative was dismissed by Republican Wiggins as “Waldie’s fable.”

Sandman moved to strike the first paragraph of the Sarbanes articles and threatened to make the same move against eight other paragraphs. When a vote was finally held late Friday night, Sandman’s move was defeated by the same 27 to 11 margin (although there was some shifting of sides in the two votes). That took much of the steam out of a peripheral argument that centered on form rather than substance.

The Facts Behind the Charges

By the next day, Sandman, at least, saw little benefit in pursuing the fight over specificity. “The argument was exhausted yesterday,” he conceded to the committee, then withdrew his other eight motions to strike portions of the article under consideration. But now, having been harassed for their failure to detail each general complaint against Nixon, the Democrats were more than ready. They turned the tables, introducing motions to strike paragraphs as a means of debating the facts behind each charge.

That was as time-consuming as had been the Republican tactics of the day before, although Democrats argued that the educational value of explaining each charge was worthwhile.

The tactic was led by Flowers, who introduced the strike motion, then yielded his time to sympathetic colleagues. Cohen also took advantage of the situation by securing time to buttress his contention that Nixon had withheld evidence from various Watergate investigators. Sandman protested the reversed situation, complaining that the proceedings were achieving little and boring the viewing public. Nevertheless, some enlightening and sharp exchanges of views on facts of evidence were televised throughout Saturday afternoon and into the evening.

Wiggins and Dennis among the Nixon loyalists were pitted against Democrats George Danielson, Wayne Owens and Hungate. Every time a vote was taken on Flowers’ motions to eliminate paragraphs, the proposals lost decisively; most of the time Flowers merely responded “Present,” not voting on his own motion. When Sandman found it amazing that Flowers was not voting for his proposals, the Democrat got the laugh of the day by replying, “Well, the caliber of the debate is so outstanding that it leaves me undecided at the conclusion.”

The reality of the debate was that no minds on the committee were being changed, but the cases for and against the President were being staked out for the showdown on the floor of the House. Noting the Democratic lineup against him on the committee, Sandman told fellow Nixon supporters: “You’re going to have a far better forum on another day — in the House.”

Finally all of the amendments were dispensed with and Chairman Rodino asked for the vote on the articles presented by Sarbanes, as amended slightly, even though all knew what the general outcome would be; the ensuing tense roll call was a moving, memorable moment. The only “Aye” that questionable caused a vote was murmur to that of ripple Froehlich, through the who cast a otherwise si soft lent crowd of fewer than 300 reporters and spectators.

Several of the Congressmen bowed their heads as the vote was taken. Arkansas’ Thornton closed his eyes as if in prayer.

Democrats Seiberling and Mann and Republican Wiggins appeared close to tears. Almost all the “Ayes” were delivered in mournful, almost sepulchral tones. By contrast, the first “No” — from Edward Hutchinson — sounded buoyant and was accompanied by a thin smile.

After the Sarbanes substitute article passed, the final vote on the article as amended was anticlimactic, even though it marked the official passage of the first impeachment article against Nixon. “Article I of that resolution of impeachment will be reported to the House,” Chairman Rodino announced just be fore recessing the committee.

This week its deliberations on other proposed articles will begin. An article charging the President with abusing the powers of his office seems likely to pick up the same margin of sup port, possibly with the addition of Republican McClory. He is also expected to introduce an article of his own, charging Nixon with contempt of Congress for failing to respond to the Judi Committee’s subpoenas.

Moving on to the House

If the committee completes its voting on the articles early this week as expected, its staff would be given about a week to prepare a final committee report on the specifics of the case against the President. A majority of the committee would have to approve that report before it is transmitted along with the articles to the House Rules Committee. That committee is expected to re port the articles for full-scale House debate beginning about Aug. 12, with a House vote coming perhaps Aug. 23. Quick approval for televising those proceedings is expected to be granted by vote of the House.

Already speculation has begun on who will be managers of the House case if a Senate trial is held. Chosen by the House lead ers from the membership of the Judiciary Committee, they will act as the prosecutors in the trial. It is assumed that Rodino will be chairman of the managers and that another likely prospect is Democrat Sarbanes. A Southern Democrat, most probably Mann, may be offered such a position, but the chances of coaxing a Republican to share the work are not great.

Just when the Senate trial may begin would depend on how much time Senate leaders wish to accord the President and his lawyers to prepare their defense case. Two or three weeks is the period being discussed, so unless the House schedule slips badly, a trial presumably could start by the middle of September.

Although it is far from certain, the tapes subpoenaed by Special Prosecutor Jaworski from the President could play an influential role in the Senate trial. Just how and when any Congressional investigators could acquire them is not clear either, since the Supreme Court directed that the tapes be made available for use in the criminal-conspiracy trial of six former Nixon aides, scheduled to begin on Sept. 9. For eight hours after the Supreme Court decision was announced in Washington, the San Clemente White House kept alive its earlier suspense about whether the President would comply. But then James St. Clair stepped into a Laguna Beach pressroom to announce that Nixon had directed him to “take whatever measures are necessary to comply with that decision in all respects.” Some legal experts believe that the Senate could subpoena the tapes from Judge Sirica in ample time for a presidential trial.

At a hearing in his courtroom, Sirica reminded St. Clair that “a little over three months have passed since the subpoena was issued.” Nixon’s lawyer promised to “do as good a job as promptly as possible” but said that Jaworski’s suggested ten-day deadline could not be met. The President, St. Clair said, “feels he should know what he is turning over” and thus must listen to all of the tapes.

Said Sirica moments later: “I don’t think it’s going to take the time you have in mind.” Suddenly he asked St. Clair: “Have you personally listened to the tapes?” When St. Clair said no, Sirica was incredulous. “You mean to say the President wouldn’t approve of your listening to the tapes?” Flustered, St. Clair did not directly respond. Sirica persisted: “You mean to say you could argue this case without knowing all the background of these matters?” St. Clair claimed that he was not a good listener. The judge sternly suggested: “You should personally undertake that assignment [analyzing the tapes].” St. Clair agreed to supply 20 of the 64 tapes early this week and hoped to have another batch ready by week’s end.

Such was the accelerating momentum of impeachment, however, that any new evidence from the tapes may be overkill. By its diligence and the bipartisan magnitude of its vote, the House Judiciary Committee has virtually assured a substantial, bipartisan vote for impeachment in the full House. That in turn is sure to have an impact on the Senate, as will public opinion.

Last week a Gallup poll showed that Nixon held a favorable rating of only 24% of the population, his lowest level yet. A Harris poll found that 53% of Americans favor the President’s impeachment by the House and a plurality, 47% to 34%, believes that he should be convicted in the Senate and dismissed from office.

Both polls were taken before the massive exposure to the nation of evidence and argument in the committee’s televised sessions —and the committee’s vote. In the proceedings that lie ahead, those figures are likely to turn further against Nixon, and the evidence that brought the men and women of the committee to their anguished decision is not likely to go away.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com