On July 8, 1879, at 4 o’clock in the afternoon, a refitted Royal Navy gunboat called the U.S.S. Jeannette left San Francisco headed for the North Pole. The expedition was sponsored by the newspaper magnate James Gordon Bennett, who’d had some luck with this kind of thing before: he’s the one who sent Stanley to Africa to find Livingstone. The Jeannette was heated and insulated. Its hull was reinforced with trusses and beams to withstand the pressure of Arctic pack ice. It carried a set of arc lights supplied by Thomas Edison; its telephones and telegraph were from Alexander Graham Bell. Its hold was stuffed with provisions for three years. It never came back.

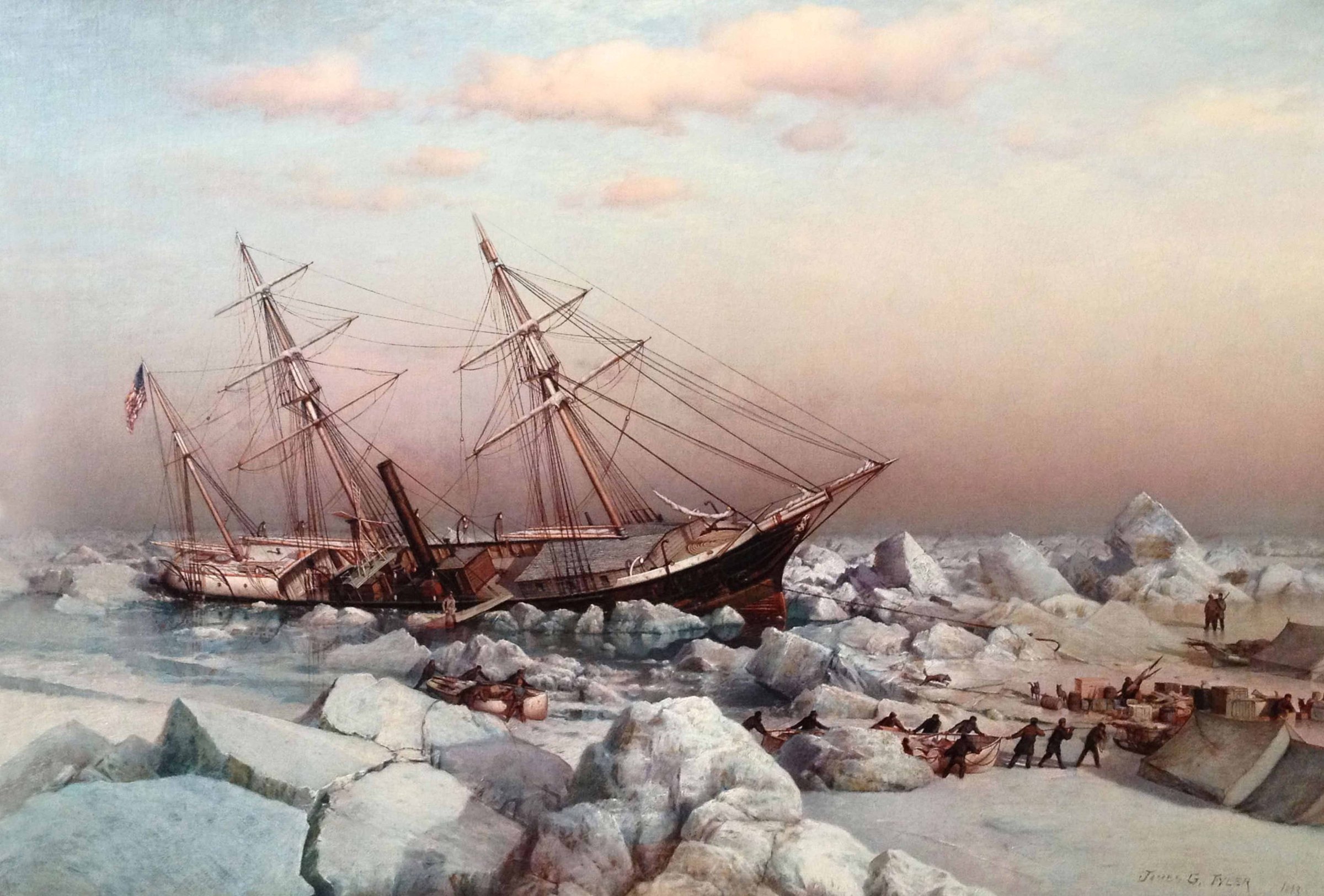

To an aficionado of the genre, narratives of early Arctic exploration unfold with a certain formal inevitability, in stately, familiar, unvarying stages. The fitting and provisioning of the stout vessel, the gala departure, the fruitless exploration of blind bays and dead islands, the fading hopes, the trapping of the ship in pack ice, the fatal nightmare of cold and starvation. Finally, as an epilogue, a new expedition sets out in search of the first, and the cycle starts again.

The predictability of it all in no way detracts from the fascination. If anything, it enhances the awful fatedness that haunts these stories. Hampton Sides isn’t a scholar of the Arctic; he writes narrative histories–his last book was Hellhound on His Trail, about the hunt for the assassin of Martin Luther King Jr. But he brings vividness to In the Kingdom of Ice, and in the tragedy of the Jeannette he’s found a story that epitomizes both the heroism and the ghastly expense of life that characterized the entire Arctic enterprise.

The captain of the Jeannette was a resourceful former naval officer named George Washington De Long. Ironically, De Long’s introduction to the Arctic came on a search for yet another lost vessel, the Polaris, which disappeared off Greenland in 1872. (The Polaris was never found, but seven months later, 19 survivors were discovered adrift on an ice floe.) The experience left De Long with an Arctic obsession; he was fascinated “by its lonely grandeur, by its mirages and strange tricks of light, its mock moons and blood-red halos, its thick misty atmospheres that altered and magnified sounds.”

Granted, the Arctic was a lot more seductive back when no one knew what was up there. At the time, scientists theorized that the North Pole was covered by a body of warm, ice-free water they called the Open Polar Sea, accessible by a “thermometric gateway,” a soft spot in the ring of ice that surrounded it. Nobody had found the gateway yet, but God help him, De Long was going to try.

By September the Jeannette had been frozen into the ice pack–“nipped,” in the parlance–but that was part of the plan. The plan was also for the ice pack to let them out the following summer, but it didn’t. The crew of 33 spent all of 1880 stuck there. They had a feast on Christmas and a variety show on New Year’s Day, but the boredom must have been acute. “He is recorded to have had many trials and tribulations,” De Long wrote in his journal. “But so far as is known, Job was never caught in pack ice.”

It’s not boring to read about all this. Ice squeezed the ship so hard that beads of tar and pine sap oozed from its boards. “Geysers of surf hissed through cracks in the ice,” Sides writes. With an eye for the telling detail, he sketches the crew members as individuals, including the ship’s engineer, an indefatigable man named Melville, and ordinary seaman William Nindemann, who displayed almost supernatural strength and imperviousness to cold–he was one of the 19 who survived the wreck of the Polaris.

The bare facts of what happened to the Jeannette’s crew are easily Googleable, but if you don’t already know the story, In the Kingdom of Ice reads like a first-class epic thriller. De Long and his companions became explorers of not only unknown geographical territory but also extremes of suffering and despair. In his stoic endurance of disappointment and pain, De Long rivals Louis Zamperini, the hero of Laura Hillenbrand’s Unbroken. What must have made it harder was that it was a waste and they knew it: De Long realized early on that there was no Open Polar Sea, no thermometric gateway, just an expanse of dead ice. It was Nindemann, the heroic ordinary seaman, who put it best. “I believe in nature,” he said. “I don’t believe in the hereafter. This world is where we get all our punishment.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com