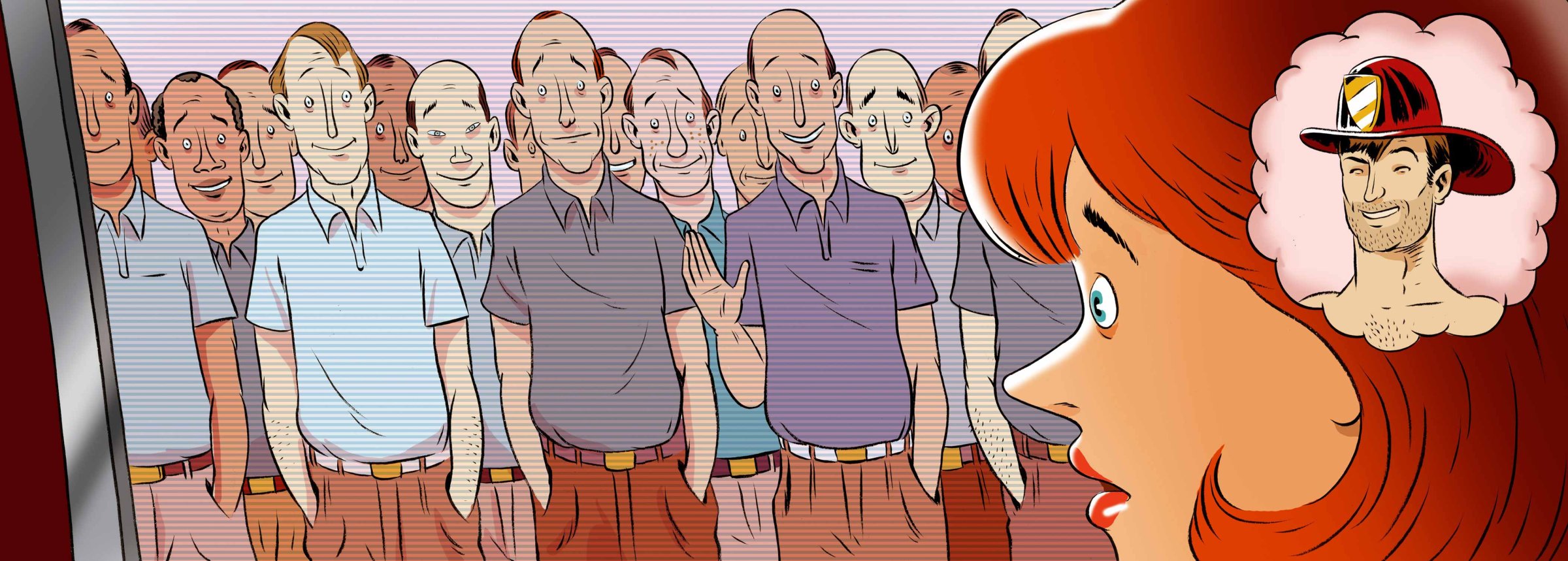

Turns out I don’t love firefighters. I thought I did. They were always my emergency responders of choice. If anything really bad were going to happen to me, I secretly hoped it would be a fire rather than, say, a cerebral hemorrhage or an attack by a knife-wielding madman, so that strapping firefighters would come to my aid rather than paramedics or cops. But according to the online dating service Zoosk, I’ve been deluding myself for years.

Earlier this year I decided to take Zoosk for a spin for a few weeks to see what I could learn about the mechanics of attraction. I chose Zoosk because it stakes its reputation on behavioral matchmaking, the newest flavor of digital dating. The biggest sites–like Match, eHarmony and OkCupid–direct people to each other mostly on the basis of personality profiles and questionnaires about their preferences in a mate. Zoosk asks fewer questions and relies more on users’ actions to bring them together.

Much as Netflix recommends movies you might want to watch based on films you’ve already sat through, Zoosk says it can figure out what you like in a person by analyzing your behavior on the site. Whose profile do you look at longest? What do the folks you respond to have in common? Sociologists and market-research professionals have long known that what people say they want to do and what they actually do are two very different things. As David Evans, a consultant to online dating businesses, puts it, “Why do you say you want a 6-ft. 2-in. lacrosse player and keep checking out the profiles of short Asian dudes?”

Ordinarily, people who use Zoosk are shown potential dates but not given any reason why the service thinks these people are right for them. The plan in my case was to spend a few weeks on the site and then get its techies to let me in on the results. They would tell me what I liked in guys and not just what I thought I liked. Full confession: I am not actually in the market for a new partner. That is, not on most days. I’m married. To make my project a little more interesting, I signed my husband up on the site as well, to see if we could find our way to each other. Of course, I asked his permission before doing so. Or at least, not long after.

After several weeks of research and immersion in Zoosk, I made an important discovery: I need to be much nicer to my husband. I can’t go back out there. Dating on Zoosk felt like shopping for a wedding dress in a thrift store–there’s not a lot of choice, and what there is seems kind of random.

To be fair, my experiment was hampered by some methodology flaws. The first was that there was no way I was putting a real photo of myself on the site. The photo-agency image I initially selected as most like me depicted, the caption said, “a woman with a headache.” So I went instead with a picture of a normal-looking older lady, who, my son later observed, was better-looking than I am. The second flaw was the fact that I have always been terrible at any sort of dating, and I suspect that years of practicing journalism may have made me worse. I opened one online chat by asking a guy why his skin was such a strange color. I was extremely suspicious with a guy who was 56 and never married. And I had to refrain from pestering a man for hard numbers when he said he wanted a woman who was “sexually insatiable.”

But I did my best to mingle and engage. “The whole beauty of behavioral matchmaking is that we don’t need that much interaction to find the biggest nuggets about the person,” says Zoosk’s co-founder and president, Alex Mehr. “About 80% of someone’s preference comes out in the first few interactions.” And Zoosk, as with most dating websites, offers up myriad ways to talk to strangers. There’s a carousel of guys, a process of winking and sending digital gifts, a messaging service and a search function. And there’s a thing called SmartPick. You get one guy a day who has been carefully selected for you based on your prior activity. It was not, as I was hoping, that you get a really bright guy.

Essentially since the dawn of the Internet-dating era, we’ve been engaged in a massive longitudinal study of mate selection. To conduct the experiment, we’ve opened the partnering floodgates. Finding a consort has gone from choosing between maybe two options presented by your family to finding a suitable person in your neighborhood and social circle to cherry-picking from among the scores of contenders you meet at school or college or work to scrolling through thousands of faces on a phone. In terms of choice, that’s like going from eating whatever Mom is serving for dinner to carrying a plate around an all-you-can-eat buffet stocked by every restaurant in the world while people dump food onto it.

Using Big Data and predictive modeling, dating websites hope to act as filters, funneling people to the most promising candidates. The rewards for a better matchmaking model are high: about 10% of all Americans and 20% of 18-to-35-year-olds have tried online dating, according to Pew Research. The activity has lost much of the stigma it attracted since Pew’s last study on it, just eight years ago. For young urban people, it’s almost mandatory, and nearly 40% of all people who’d like to find love are looking for it online. This is partly why Zoosk has filed for an IPO.

But the promise has not panned out. Pew found that only 11% of couples in a committed relationship formed in the past 10 years met their partner online. Fewer than a quarter of all online daters have scored a long-term relationship or marriage as a result, and a depressing 34% have never been on an actual date, in which people’s bodies are in the same room, as a result of their web browsing.

So are there ways we might improve the outcomes in the online dating game? Does analyzing my interactions help a service get a truer picture of me and my preferences than the one I provide in a questionnaire? “The jury is still out on behavioral matchmaking,” says Paul Oyer, a labor economist at Stanford University and the author of Everything I Ever Needed to Know About Economics I Learned From Online Dating. “The biggest impediment in all online dating is the dishonesty.” In this case, he doesn’t just mean the inaccurate picture given by misleading answers to a questionnaire but also the unreliable data that users offer up: the inflated job descriptions, the 10-year-old photographs. (Even my photo was false, remember.) Either the computer introduces the wrong people because it has been lied to, or people are attracted to a poor match because they’re being lied to. The duplicity cuts both ways: OkCupid recently admitted that in hopes of improving its algorithm it misled some users about their compatibility with one another.

All the same, the behavioral approach, which is practiced to some degree by all the big dating websites except slot-machine services like Tinder, might still help you achieve some insight into your real desires. Even before the techies crunched my numbers, I noticed some things I hadn’t realized about my mating habits. I liked men with no hair (especially if my other option was bad hair), I liked outdoorsy guys, and I tended to discount guys who used the word LOL more than, say, seven times in any one personal essay. I was shocked by how many guys thought the most lady-worthy photos were of their motorbike, boat or recently caught fish or showed themselves frowning into their camera phone while sitting in their car at a stoplight. Also, if someone were to base a whole dating website on my deal breaker, it would be called EwNoMuscleShirtPlz.com.

When my husband’s photo came up on my search, I chose the option to like it, stared at him for a while in profound gratitude, read his profile and moved on. But in 13 weeks he never came up as a SmartPick, nor in my carousel, possibly because he wasn’t a paying customer. (According to Zoosk, we were about a 60% match.) And he didn’t get that many requests to chat either. That might have been because I posted a photo of him wearing a wedding ring. He got an alert that I wanted to chat but says he wouldn’t have clicked on that photo.

When Zoosk president Mehr explained my online selections to me several weeks later, he told me, in a nice way, that I was a horrible elitist: my most consistent mating practice was to choose guys who had at least one college degree. “Education was the strongest factor,” he said, “then attractiveness, then age.” Much of this was not a big revelation, since in a short questionnaire I had said I liked educated guys and preferred to date a nonsmoker with kids. My behavior held true to those patterns. One surprising nugget: I preferred guys who were 10 years older (my husband is a year younger) and mildly favored guys who listened to Top 40 (the stuff my husband hates most, after jazz and my Carol Channing impression).

I never imagined myself with an older guy. But I realized that I never responded to guys who were younger than me, even if they were attractive and college-educated. And it wasn’t because I don’t like younger guys. It was because I was certain they wouldn’t be into me. I was afraid of being spurned, even from guys who never had a hope in the first place. Fear of rejection may also explain why I’ve had the same job for so long, have changed cities only once and rarely call my mother.

Come to think of it, it might even explain the firefighter thing. A firefighter is the one type of guy who, no matter how bad the situation is, is still going to come and get you. Hopefully not in a muscle shirt.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com