For the year’s most powerful and impassioned movie performance, you must see Jodorowsky’s Dune, a documentary feature that traces the attempt in 1974 of the shaman filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky to follow his cult hits El Topo and The Holy Mountain with an adaptation of a book he had not read: Frank Herbert’s science-fiction saga Dune.

“What if the first film of that nature had been Dune and not Star Wars?” asks Drive director Nicolas Winding Refn. “Would the whole megabucks-blockbuster structure have been altered?” Having been shown the book of storyboards that put the whole project on paper, Refn says, “I saw Dune, and it was awesome.”

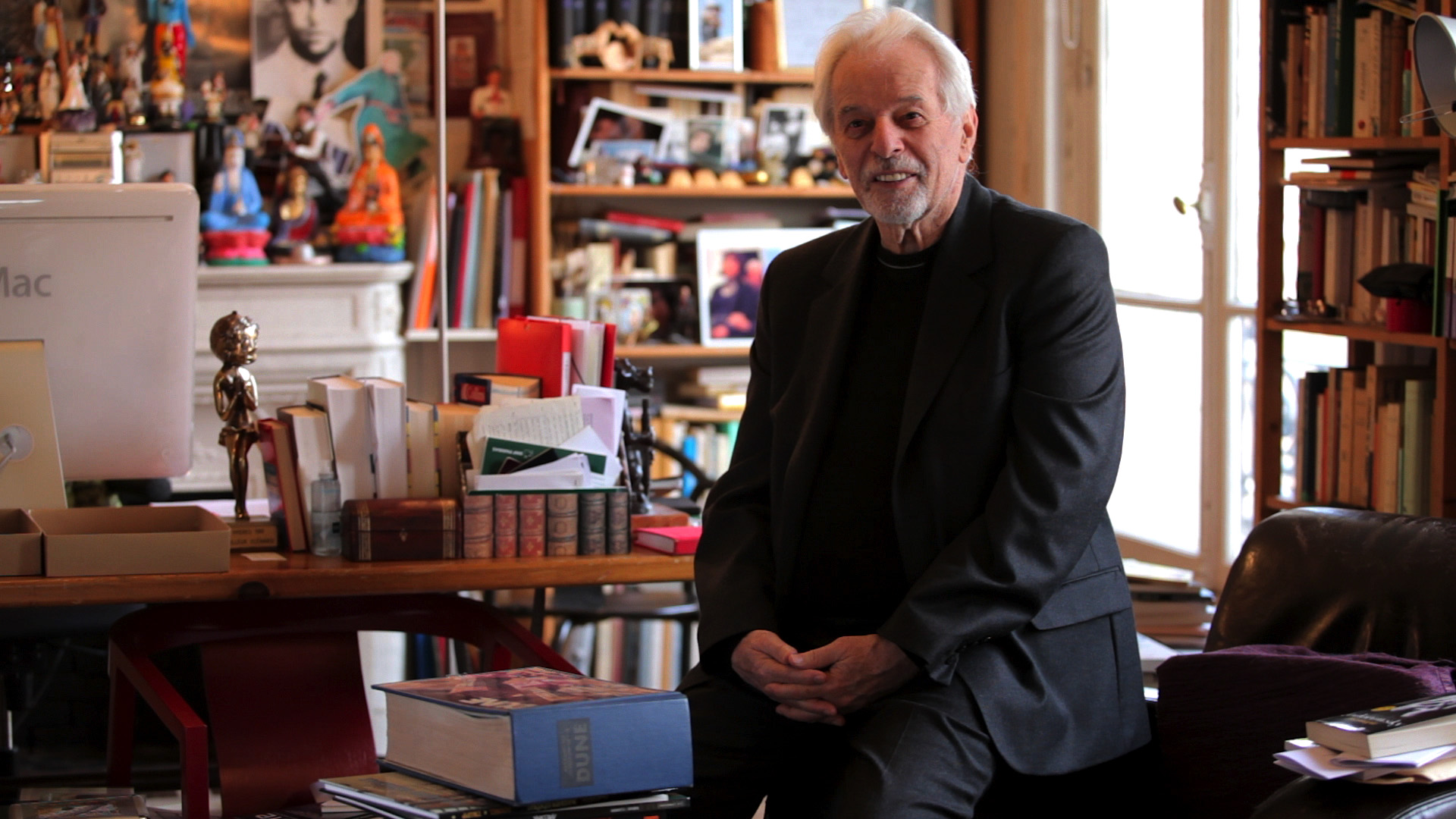

Jodorowsky’s dream movie remained only a dream: producer Michel Seydoux, after getting rejections from every Hollywood studio, came up $5 million short on the $15 million budget. (A pity that a rich entrepreneur like Megan Ellison, who backed Zero Dark Thirty, The Master, American Hustle and Her, wasn’t born yet.) And nearly four decades later, Jodorowsky acutely feels the pain — not just of the crushing of his project but also of a business model that needs financing for a brilliant madman’s artistry. Still vital and charismatic at 84, the Chilean-born director opens old wounds as if they were fresh cuts and speaks in urgent broken English:

“This system make us of slaves. Without dignity, without depth. With a devil in our pocket. The incredible money are in our pocket. [Pulls some bills from his trousers.] This money, this shit, this nothing. This paper who have nothing inside. Movies have heart — boom, boom, boom! Have mind [mimes lightning bolts from his brain]. Have power [points to his genitals]. Have ambition! I want to do something like that. Why not?” He looks anguished, spent. He might just have relived the yearlong fever of preparing Dune and the desolation of receiving the news that his beautiful child was stillborn.

Today’s moviegoers and film moguls, recalling the expensive flop that David Lynch made of Dune in 1984, might think the story unfilmable (though the Sci-Fi Channel had a hit with a nine-hour version of the Herbert trilogy in 2000 and 2003). Skeptics might also shrug at the ravings of a man like Jodorowsky demanding cold cash to pay for his cinematic delirium. That sounds like common sense, but it only underlines how timid and conservative the producers and consumers of movies have become.

(MORE: Richard Corliss’s mixed review of David Lynch’s Dune)

They should be reminded of two things. First, that several studios turned down George Lucas’ proposal for Star Wars. And second, that in the decade from the late 1960s through the mid-’70s, filmmakers often hatched extreme, unique, original visions — among them Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend, Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool, Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, Dusan Makavejev’s W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism, Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris, Werner Herzog’s Aguirre the Wrath of God and, we might say, Gerard Damiano’s art-porno Devil in Miss Jones. (Not to mention Jodorowsky’s own hallucinogenic features.) Directors dared to make those movies; audiences flocked to see them.

For his Dune doc, Frank Pavich reconvened the director, the producer and some of the movie’s “spiritual warriors” — concept artists H.R. Giger and Chris Foss, comic-book artist Jean (Moebius) Giraud and screenwriter-designer Dan O’Bannon, who died in 2009 and is represented by voice tapes and his widow Diane — plus Internet movie critics Drew (Moriarty) McWeeny and Devin (Badass) Farici. All sing psalms and dirges over a brief, glorious age when the medium attained artistic maturity — before it sank quickly, and perhaps permanently, into focus-group entertainment for the lowest common denominator. The message to take from Jodorowsky’s Dune: movies once had brains and balls, and lost them.

(MORE: When Gerard Damiano turned porn into art)

“You can’t have a masterpiece without madness,” says Seydoux, and Jodorowsky’s temperament qualified on both counts. Spawned in Mexico City’s experimental theater, where he had directed plays by Beckett and Ionesco as well as weird adaptations of Shakespeare and Strindberg, he came to movies with the 1968 Fando and Lys, based on Fernando Arrabal’s work; check out the scene in which a woman gives birth to pigs. He then exploded on the midnight-movie scene in 1971 with El Topo (The Mole), a loopy extension of Sergio Leone westerns into a metaphysic of a child (Jodorowsky’s 7-year-old son Brontis) burying all memories of his family to become a man. El Topo was downright linear compared with the 1973 The Holy Mountain, in which a Christlike “alchemist” played by Jodorowsky acquires apostles, one from each planet in the solar system, to renounce greed and find a new Ararat. A hit in Europe, The Holy Mountain made a convert of Seydoux, who offered to finance Jodorowsky’s next project.

On a friend’s recommendation, he picked Dune, which he soon envisioned as a mind-expanding movie. “I wanted to make a film that would give people who took LSD the hallucination without taking the drug,” he says here. “I wanted to change the young minds of all the world.” The film’s first shot, inspired by the three-minute opening of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil, would send the camera “traversing the whole universe” until it landed on the Dune planet. Having finally read the Herbert novel, he used some parts, ignored others and created a new ending. “I was raping Frank Herbert,” the director says in one of his many inflammatory metaphors, “but with love.”

(MORE: Why Dune is Lev Grossman’s 101st choice for the all-TIME 100 Books list)

A spellbinding salesman whose giant ego could convince other great eccentrics, Jodorowsky persuaded Salvador Dalí to take a role by agreeing to his price of $100,000 for every minute Dalí appeared on screen. He claims he convinced Welles to play the immense Baron Harkkonen by promising that the chef of Welles’ favorite Paris restaurant would cater the shoot. He ran into Mick Jagger at a nightclub and told him he wanted the Stones singer to play the Baron’s son Feyd. “And he said only one word: Yes.” (The Lynch movie made do with Kenneth McMillan as the Baron and Sting, in gold-leaf bathing suit, as Feyd.)

These tales — as well as the stories about casting David Carradine and signing Pink Floyd and the French band Magma to compose music for Dune — may be accurate or may be more Jodorowsky fantasy. One may also question the assertions by McWeeny and Farici that elements from later sci-fi films, including Star Wars, Blade Runner, The Terminator and RoboCop, were somehow directly inspired by Jodorowsky’s unmade movie. The director’s son Brontis, who was to play the main character Paul, insists, “You can hear in some films, ‘I am Dune,’ ‘I am Dune.'” Yet the makers of those later films may not have seen Jodorowsky’s storyboards; it’s the old post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. (One movie that does bear Dune’s fingerprints is the Ridley Scott Alien, for which O’Bannon wrote the script, Foss contributed some designs, never used, and Giger created the alien in its various metamorphoses.)

(MORE: Frank Rich’s 1979 review of Alien)

What rings true is the director’s sacred if not entirely sane commitment to his art. “If I need to cut my arms [off] to make a picture,” he avers, “I will cut my arms.” Told by Hollywood that his Dune movie should be just 90 minutes long, he shouts, “Why one hour and a half? I will make a film of 12 hours! Or 20 hours!” and ends with a plaintive plea, “It’s a dream. Don’t ruin my dream.”

A beautiful dream, ruined, is the theme of Pavich’s film and of two other movies about unfinished movies: the 1965 The Epic That Never Was, detailing Josef von Sternberg’s attempt to film Robert Grave’s I, Claudius with Charles Laughton as the Roman emperor, and the 2002 Lost in La Mancha, outlining Terry Gilliam’s troubles with filming Don Quixote, which was to star Jean Rochefort as Quixote and Johnny Depp as Sancho Panza. Maybe the movies, if completed, wouldn’t have been so great. But in their makers’ memories and their fans’ fantasies, every dream comes true, every mad ambition achieved.

Like the Sternberg and Gilliam films, Jodorowsky’s version of Dune is a prime exhibit in the alternate history of film masterpieces — the Museum of What If. Given the energy and talent poured into the project, and Jodorowsky’s undiminished passion for it, we can almost accept, on faith if not in fact, the estimation of Hardware director Richard Stanley: “Dune is probably the greatest movie never made.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com