Now there are three Lucys I have to keep straight: The 3.2 million year old Australopithecus unearthed in Ethiopia in 1974; the eponymous star of the inexplicably celebrated 1950s sitcom I Love Lucy; and, most recently, the lead character—played by Scarlett Johansson—of the new sci-fi thriller straightforwardly titled Lucy. Going by intellectual heft alone, I’ll pick the millions-year-old bones.

The premise of the movie, such as it is, is that Lucy, a drug mule living in Taiwan, is exposed to a bit of high-tech pharma that suddenly increases her brain power, giving her the ability to outwit entire police departments, travel through time and space, dematerialize at will and yada-yada-yada, cut to gunfights, special effects and a portentous message about, well, something or other.

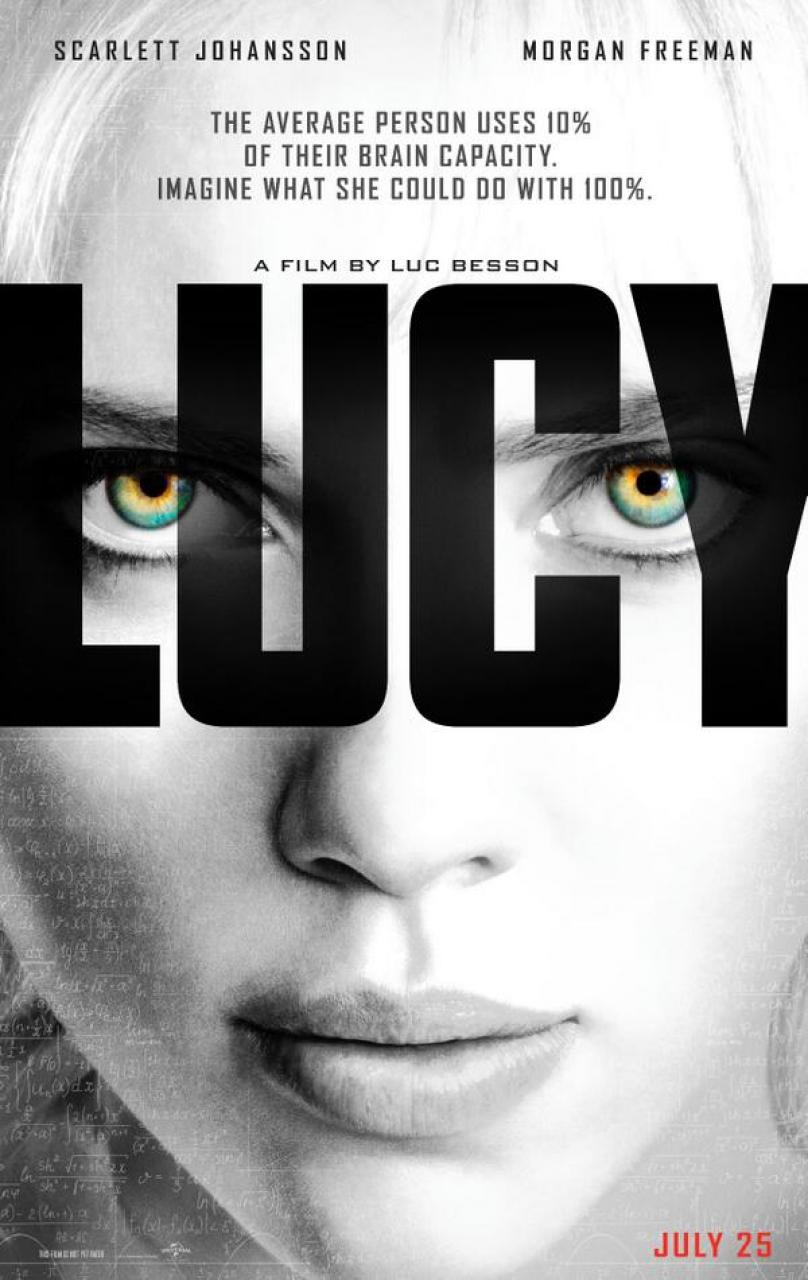

The movie poster’s teaser line? “The average person uses 10% of their brain capacity. Imagine what she could do with 100%.”

Let’s forgive the poster its pronoun problem (the average person—as in just one of us—uses 10% of their brain capacity), because the science problem is so much more egregious. The 10% brainpower thing is part of a rich canon of widely believed and entirely untrue science dicta that include “Man is the only animal that kills its own kind” (tell that to the lion cubs that were just murdered by an alpha male trying to take over a pride) and “A goldfish can remember something for only seven seconds” (a premise that was tested…how? With a pop quiz?).

No one is entirely sure where the 10% brainpower canard got started, but it goes back at least a century and is one of the most popular entries in the equally popular book 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology. There is some speculation that the belief began with an idle quote by American philosopher William James who, in 1908, wrote, “We are making use of only a small part of our possible mental and physical resources,” an observation vague enough to mean almost anything—or nothing—at all.

Some people attribute it to an explanation Albert Einstein offered when asked to account for his own towering intellect—except that Einstein never said such a thing and even if he had it would not make it true. Still others cite the more scientifically defensible idea that there is a measure of plasticity in the brain, so that if the region that controls, say, the right arm, is damaged by, say, a stroke, it is sometimes possible for other parts of the brain to pick up the slack—a sort of neural rewiring that restores lost motion and function.

But none of that remotely justifies the 10% silliness. The fact is, the brain is overworked as it is, 3 lbs. (1,400 gm) of tissue stuffed into a skull that can barely hold it all. There’s a reason the human brain is as wrinkled as it is and that’s because the more it grew as we developed, the more it bumped up against the limits of the cranium; the only way to increase the surface area of the neocortex sufficiently to handle the advanced data crunching we do was to add convolutions. Open up the cerebral cortex and smooth it out and it would measure 2.5 sq. ft. (2,500 sq cm). Wrinkles are a clumsy solution to a problem that never would have presented itself in the first place if 90% of our disk space were going to waste.

What’s more, our bodies simply couldn’t afford to maintain so much idle neuronal tissue since the brain is an exceedingly expensive organ to own and operate—at least in terms of energy needs. At birth, babies actually have up to 50% more neural connections among the billions of brain cells than adults do, but in the first few years of life (and, to a lesser extent, on through sexual maturity) a process of pruning takes place, with many of those synaptic links being broken and the ones that remain growing stronger. That makes the brain less diffuse and more efficient—which is exactly the way any good central processing unit should operate. It also allows it to use up fewer calories, which is critical.

“We were a nutritionally marginal species early on,” the late William Greenough, a psychologist and brain development expert at the University of Illinois, told me for my 2007 book Simplexity. “A synapse is a very costly thing to support.”

Added Ray Jackendoff, co-director of the center for Cognitive Studies at Tufts University, “The thing that’s really astonishing might not be that we lose so many connections, but that the brain’s plasticity and growth are able to continue for as long as they do.”

OK, so the Lucy screenwriters aren’t psychologists or directors of cognitive studies institutes. But they do have the same 100 billion neurons everybody else’s brains have. Here’s hoping they take a few billion of them out for an invigorating run before they write their next sci-fi script.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com