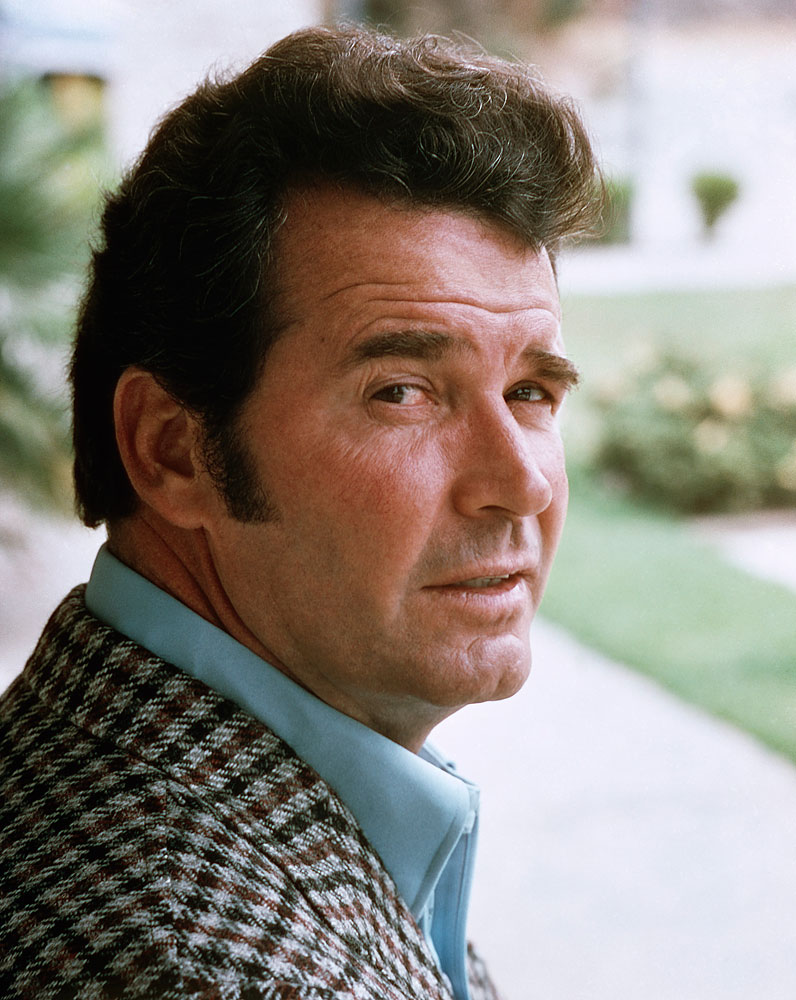

He was a man’s man who relied on his wits instead of his fists; a ladies’ man who wouldn’t steal a fella’s girl. Famous for his Maverick Western series in the 1950s and The Rockford Files in the ’70s, and in movies like The Great Escape and Grand Prix in between, James Garner played amiable, independent characters for more than a half-century, and never lost his comforting, enduring appeal. He was like a pair of boots you wear for decades and never want to throw out.

In real life Garner was apparently the same: straight shooter, decent guy. When he thought a movie studio or TV network was doing him dirt, he’d sue them, and win. When in 1956 he met a girl he liked, and married her two weeks later, he stayed married till he died — late Saturday night, at 86, in his Los Angeles home.

Compare him with other stars who found their footing in early TV Westerns, and see what made Garner a natural for the small screen. He lacked Clint Eastwood’s mulish brand of menace, Steve McQueen’s sexy recklessness, Burt Reynolds’s self-parodying machismo. Garner didn’t simmer with resentment, wasn’t tattooed with old traumas. “Lady,” his Bret Maverick says to a scheming woman in an early episode, “I never worry about anything.” The actor’s ease with his character and himself made Maverick a welcome weekly visitor in America’s living rooms for three seasons.

And though he graduated to leading-man status in major studio feature films before Eastwood, Reynolds and McQueen did, and stayed there for more than a decade, Garner felt more at home on TV, where he found The Rockford Files waiting in 1974, and where his nearly unique level of affability was treasured, not taken for granted.

(READ: James Poniewozik’s tribute to James Garner)

Try to describe the character Garner created, and again you have to start by saying what he wasn’t. He didn’t fit any of the extreme Hollywood fashions for its heroes. He was not a loner or a joiner, not a fighter or a father type. In performance style he was neither a comedian of the broad stripe nor a let-them-see-and-feel-my-pain dramatic actor. He was pure affability, clever, charming and confident — just about the embodiment of how Americans liked to picture themselves back then, at the postwar apex of their nation’s power.

Born in Norman, Okla., on Apr. 7, 1928, James Scott Baumgarner couldn’t have been more American: his mother was half-Cherokee. She died when he was a kid, and he took some licks from his father’s second wife. He got out of town as soon as he could, enlisting in the Merchant Marines on his 16th birthday. Later he was a soldier in Korea, earning two Purple Hearts, one for wounds caused by friendly fire — “I got in the wrong place at the wrong time,” he recalled with his usual self-depreciating wryness.

Back in the States, Jim took a while to find his calling. As he told Robert Osborne of Turner Classic Movies in 2001, “I worked the oil fields, I drove trucks, I worked in grocery stores, chicken hatcheries, worked with the telephone company, did a little bit of everything and never found a job I really liked, until I finally got into acting. And it took me about two-and-a-half, three years before I liked that.”

A fellow Okie, Paul Gregory, was an agent and producer. In 1954 he cast his protégé as a member of the court in Broadway’s The Caine Mutiny Court Martial. With no lines to speak, Baumgarner at first thought his biggest challenge was to stay awake. Instead he paid attention to the stars around him, especially Henry Fonda; he must have inhaled some of Fonda’s Midwestern effortlessness, since it would soon be a hallmark of his own approach. (“I swiped practically all my acting style from him,” Garner later said.) As the star of the 1969 Support Your Local Sheriff! — perhaps the Garneriest role of his movie career — he leans back on a chair, his feet propped up against a railing, just like Fonda’s Sheriff Wyatt Earp in My Darling Clementine… before idly trip-roping a half-dozen varmints. He seems relaxed, but he’s really paying attention, supremely assured of his abilities.

Warners put the actor under contract at $175 a week, shortened his name to Garner, and launched him in Maverick, a Roy Huggins Western that went on the air Sept. 22, 1957, against CBS’s The Ed Sullivan Show, the second highest-rated program at the time, and Steve Allen’s popular comedy-variety hour. Within a year Maverick had replaced Sullivan in the top 10, and Garner was a TV star.

He played — pretty much was, in that no-sweat, convincing way of his — Bret Maverick, gambler-rogue, inspired bluffer at five-card stud, with an eye for working scams that would rob the robbers and help the helpless. Though the show’s first three episodes (directed by Western B-movie genius Budd Boetticher) were relatively straightforward, Huggins soon exploited its young star’s way with a wry line, and Maverick became more comedy than Western. The show’s trump card was Garner’s strong, smiling demeanor, which made it a pleasure, almost an honor, to be defrauded by him. Viewers quickly afforded him the same welcome, trusting that he wouldn’t reach through the home screen and pocket the silverware.

Shooting a 50-min., dialogue-heavy episode each week proved impossible, so Huggins invented a younger Maverick brother, Bart (Jack Kelly), to fill out the season. Later an English cousin, Beau (Roger Moore), joined the series. By that time Garner had left the show, having sued his employers for breach of contract when they stopped paying him during a writers’ strike. He won by proving that Warners had secretly been banking scripts. Now he could go be a movie star.

On the big screen Garner occasionally played the dramatic stalwart; he was Audrey Hepburn’s fiancé in William Wyler’s 1962 film of Lillian Hellman’s lesbian-accusation play The Children’s Hour. (“First time I ever cried on screen,” he told Osborne. “Might’ve been the last time.”) But his usual job was squiring top actresses through romantic comedies: Doris Day in The Thrill of It All and Move Over, Darling, Kim Novak in Boys’ Night Out. Often his rom-com roles had clear echoes of Bret Maverick’s con-artistry. In the 1960 Cash McCall, he’s an early practitioner of the leveraged buyout — a Mitt Romney decades ahead of his time — with Natalie Wood as his prettiest acquisition. In The Wheeler Dealers (1963) he plays Texas oilman Henry Tyroon, as in tycoon, cozying up to stock analyst Lee Remick.

Too young to serve in World War II, Garner spent 45 years, off and on, playing roguish combatants or grizzled veterans of the European campaign, from his film-star debut in Darby’s Rangers (1959) through the 1984 Tank and up to The Notebook (2004). In his biggest movie hit, the 1963 The Great Escape he’s Lt. “Scrounger” Hendley, another gloss on Bret Maverick: he knows how to find the materials needed for a group of British and American officers to tunnel out of a maximum-security German camp. Hendley shows his skill by flim-flamming or skim-scamming the main guard, and his valor by taking a fellow prisoner who is nearly blind along the escape route. But like Maverick, Hendley discounts any heroic impulses: he says he’s getting out just so he can get home.

Based very loosely on a true story, The Great Escape is mainly remembered for the scene in which McQueen (actually a stunt double) pilots a motorcycle up a ramp and over a barbed-wire fence; the scene was there because the star, a racing aficionado, insisted on a bike stunt. Garner got second billing to McQueen, who came to early fame in the 1958 TV Western Wanted: Dead or Alive. A few years later, Garner out-McQueened McQueen by starring in John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix, a three-hour action film about Formula One drivers, their women and their cars (but mainly their cars). At the same time, McQueen was planning a similar film, Day of the Champion, that never got made. The actual Formula One drivers on the Grand Prix location said Garner was a natural behind the wheel. Score one for the Maverick.

Once in a while, a Garner character could be on the other side of the con, as in 36 Hours (1964), which casts him as a U.S. soldier knocked out and kidnapped by the Germans just before D-Day and told, when he comes to, that the war is over; the nasty Nazis hope to extract secrets of the imminent invasion. Here, as in the modern-day, Stateside Mister Buddwing (1966) — where he’s an amnesiac seeking his identity and pulling the veil off a convoluted business scheme — Garner was the potential victim. But furrowed brows and helplessness didn’t suit this emblem of congenial self-confidence. He was much more at ease playing a man at ease, who never breaks a sweat, even in the tightest corner, because he figures he can talk his way out of it.

Screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky took note of this Garner gift and ran amok with it in his script for the 1964 The Americanization of Emily, directed by Arthur Hiller. Garner is Lt. Cmdr. Charlie Madison, who has blustered his way onto a peaceful island owned by the Brits. When his superior officer goes bananas, Charlie must take on the assignment of filming the D-Day invasion, in the company of his starchy English driver, Emily Barham — Julie Andrews in the movie she made between Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music. (Garner is billed first.)

Covering the Maverick character with the soot of misanthropy, and testing Garner’s ability to spit out tongue-twister dialogue, Chayefsky handed the actor reams of cynical soliloquies, a few of which can be found here. We’ll settle for this denunciation of war lovers: “We shall never end wars, Mrs. Barham, by blaming it on the ministers and generals, or warmongering imperialists, or all the other banal bogeys. It’s the rest of us who build statues to those generals and name boulevards after those ministers — the rest of us who make heroes of our dead and shrines of our battlefields. We wear our widow’s weeds like nuns, Mrs. Barham, and perpetuate war by exalting its sacrifices.” Harrumph and gotcha! Chayefsky’s film rants would get even riper in his screenplays for The Hospital and Network, but they were never delivered with handsomer authority than Garner invested in Charlie’s antiwar speeches.

More comfortable in a saddle than on Chayefsky’s high horse, Garner made his share of movie Westerns. He played legendary lawman Wyatt Earp twice — in the 1967 Hour of the Gun and, 21 years later, in Blake Edward’s Sunset — and established a little franchise with director Burt Kennedy’s low-key hit Support Your Local Sheriff!, in which he agrees to the job because he thinks it’s easy pay. (‘Tain’t.) In Kennedy’s informal sequel, the 1972 Support Your Local Gunfighter, Garner amiably inhabits one of the oldest Western plots, of a grifter mistaken for a famous gunfighter, and sells it like the Brooklyn Bridge.

By then he was tiring of occupying the second tier of movie stardom. He returned to series TV with another Huggins show, Nichols, a slow-paced, quick-witted Western that ran only one season. (It remained Garner’s favorite TV gig.) By the ’70s, oaters were out of fashion on the small screen; detectives were in. So Garner played P.I. Jim Rockford on The Rockford Files, also produced by Huggins and with 20 of the scripts written by David Chase (The Sopranos). Over the six-year-span of the show, Garner and the writers fought with their studio, Universal, to keep injecting behavioral comedy — what the star was best at — into the whodunit plots. Eventually, Garner successfully sued Universal for his rightful share of the Rockford profits, netting a reported $14 million.

He never gave up movie work, earning an Oscar nomination for the 1984 Murphy’s Romance as the small-town druggist who loves rancher Sally Field. In Blake Edwards’ 1982 Victor Victoria he reteamed with Andrews (now Mrs. Edwards) as King Marchand, a shady Prohibition entrepreneur who falls in love with a female impersonator — that is to say, Andrews is a female, impersonating a man impersonating a woman. In their big scene, King tells Victoria, “I don’t care if you are a man” and kisses her. She says, “I’m not a man,” and he replies, “I still don’t care.” Edwards had acceded to the producers’ insistence that King know in advance the gender of the person who has smitten him; but it’s still evidence of a he-man star’s willingness to shatter what was then one of Hollywood’s sexual taboos.

In his seventies, long after quintuple-bypass surgery in 1988, Garner lassoed two of his strongest movie roles. In Clint Eastwood’s Space Cowboys (2000), he costarred as a NASA pilot from the 1950s who’s de-mothballed four decades later to help Eastwood’s Frank Corvin fix a Soviet satellite that’s about to crash to earth. Frank, who had built the technology the Russkies swiped, goes up to fix the damn thing and takes his pals along for a senior-citizen road trip to outer space. The Over the Moon Gang rides again, in an alterkocker Armageddon.

(READ: Corliss’s review of Space Cowboys)

He capped his career with a rare weepie role, in the 2004 smash The Notebook, from Nicholas Sparks’s novel. As Duke, a retirement-home resident, he reads aloud passages from a diary kept by a patient (Gene Rowlands) succumbing to Alzheimer’s disease, with flashbacks of the World War II love story enacted by Ryan Gosling and Rachel McAdams. Directed by Rowlands’ son Nick Cassavetes, The Notebook is 99 and 44/100th-percent pure soap opera, given heft and conviction by two stars with a combined century in the business. In this tale of two ordinary people living together — till death do them part, and unite — Garner strips himself naked of all smooth pride to utter his last words to his beloved: “Good night. I’ll be seeing you.”

As faithful in life as in his craft, Garner held true to the Democratic Party, for which he campaigned on behalf of civil rights and a greener Earth, and to his wife of 58 years, Lois Clarke. (Their daughter Gigi also survives him.)

Calling himself “a Methodist but not as an actor,” Garner considered acting a job; golf was his passion. He knew his lines, stood on his mark and told the truth of his characters. Is that Acting? Not in the grand sense of Stanislavski or his heirs, from Brando to Gosling. But, as Garner plied the trade, it certainly was acting of the most persuasive order. “I think Jim is such a good actor because he leaves his actor at home and brings himself to the screen,” said Gretchen Corbett, one of his Rockford Files costars, in the 2001 book The Garner Files. “He’s also a very appealing human being. Both men and women feel safe with him; they feel like they get him.”

Everyone did. And anyone would want to spend more time with that engaging maverick, that rock of American confidence, James Garner.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com