Apart from the probable cause of its destruction, we know almost nothing about the Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17 that was “blown out of the sky” yesterday over eastern Ukraine, according to Vice President Joe Biden. President Obama confirmed today that one American was among the dead and that separatists with ties to Russia are allowing inspectors to search the wreckage area. In today’s press conference, Obama stressed the need to get real facts — as opposed to misinformed speculation — before deciding on next steps.

Yet even with little in the way of concrete knowledge — much less clear, direct ties to American lives and interests — what might be called the Great U.S. Intervention Machine is already kicking into high gear. This is unfortunate, to say the least.

After a decade-plus of disastrous wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people (including almost 7,000 American soldiers) and constitutionally dubious and strategically vague interventions in places such as Libya, it is well past time for American politicians, policymakers, and voters to stage a national conversation about U.S. foreign policy. Instead, elected officials and their advisers are always looking for the next crisis over which to puff up their chests and beat war drums.

Which is one of the reasons why Gallup and others report record low numbers of people think the government is up to handling global challenges. Last fall, just 49 percent of Americans had a “great deal” or “fair amount” of trust and confidence in Washington’s ability to handle international problems. That’s down from a high of 83 percent in 2002, before the Iraq invasion.

In today’s comments, President Obama said that he currently doesn’t “see a U.S. military role beyond what we’ve already been doing in working with our NATO partners and some of the Baltic states.” Such caution is not only wise, it’s uncharacteristic for a commander-in-chief who tripled troop strength in Afghanistan (to absolutely no positive effect), added U.S. planes to NATO’s action on Libya without consulting Congress, and was just last year agitating to bomb Syria.

Despite his immediate comments, there’s no question that the downing of the Malaysian plane “will intensify pressure on President Obama to send military help,” observes Jim Warren in The Daily News. Russia expert Damon Wilson, who worked for both the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, says that no matter what else we learn, it’s time to beef up “sanctions that bite, along with military assistance, including lethal military assistance to Ukraine.” “Whoever did it should pay full price,” Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.), the head of the Senate’s Armed Services Committee, says. “If it’s by a country, whether directly or indirectly, it could be considered an act of war.”

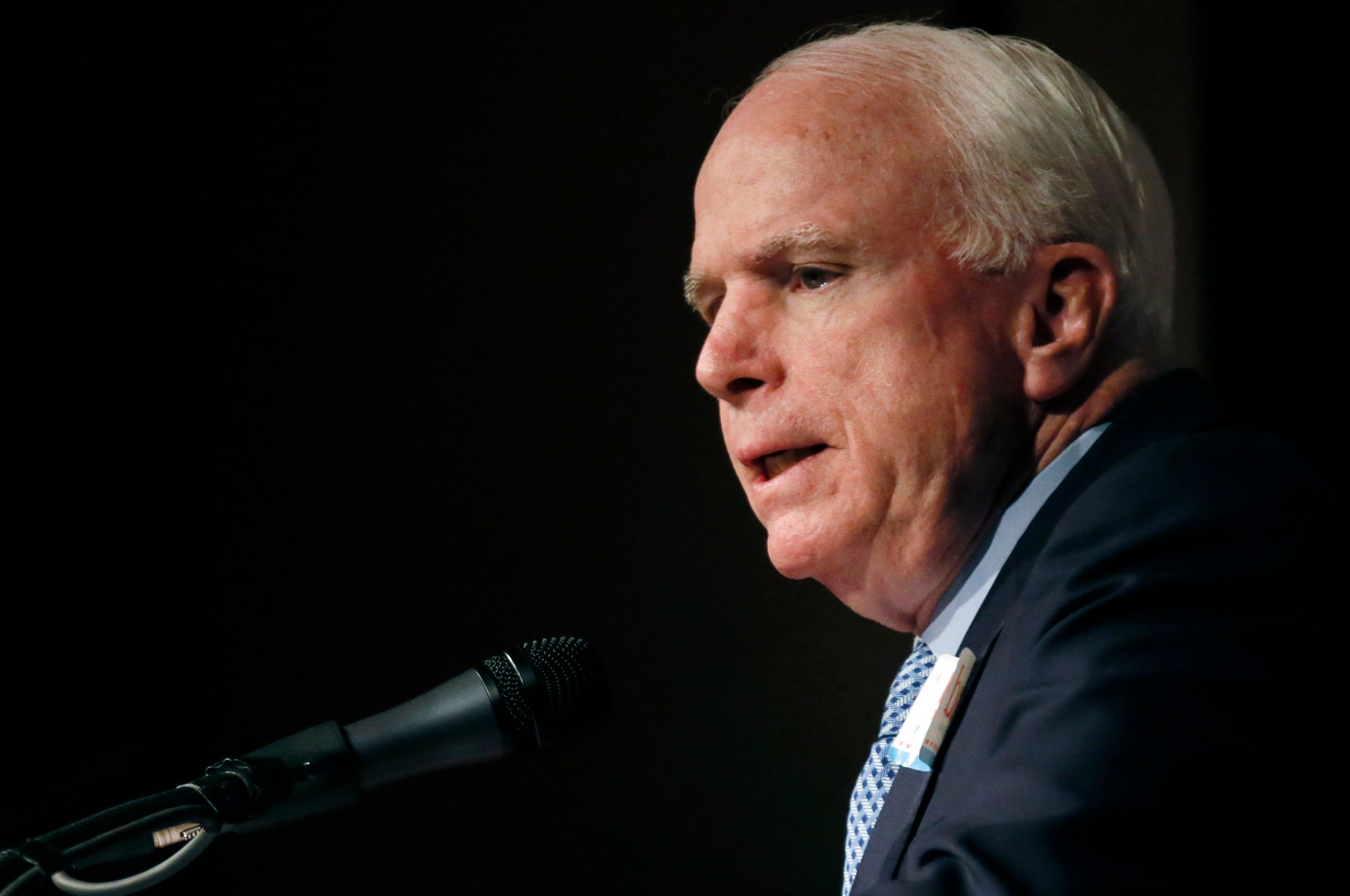

The immediate response of Arizona Sen. John McCain, the 2012 Republican presidential, was to appear on Fox News’ Hannity and fulminate that America appears “weak” under the leadership of President Obama and to imply that’s why this sort of thing happens. If the Russian government run by Vladimir Putin or Russian separatists in Ukraine are in any way behind the crash — even “indirectly” — said McCain, there will be “incredible repercussions.”

Exactly what those repercussions might be are anybody’s guess, but McCain’s literal and figurative belligerence is both legendary and representative of a bipartisan Washington consensus that the United States is the world’s policeman. For virtually the length of his time in office, McCain has always been up for some sort of military response, from creating no-fly zones to strategic bombing runs to boots on the ground to supplying arms and training to insurgents wherever he may find them. He was a huge supporter not just of going into Afghanistan to chase down Osama bin Laden and the terrorists behind the 9/11 attacks but staying in the “graveyard of empires” and trying to create a liberal Western-style democracy in Kabul and beyond.

Similarly, he pushed loudly not simply for toppling Saddam Hussein but talked up America’s ability to nation-build not just in Iraq but to sculpt the larger Middle East region into something approaching what we have in the United States. Over the past dozen-plus years, he has called for large and small interventions into the former Soviet state of Georgia, Libya, and Syria. He was ready to commit American soldiers to hunting down Boko Haram in Nigeria and to capturing African war lord Joseph Kony. In the 1990s, he wanted Bill Clinton to enter that Balkan civil wars early and often.

In all this, McCain resembles no other politician more than the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, Hillary Clinton, whose hawkishness is undisputed. Like McCain, Clinton has long been an aggressive interventionist, both as a senator from New York and as secretary of state (where her famous attempt to “reset” relations with Russia failed spectacularly when it turned out that the “Reset” button she gave her Soviet counterpart meant “overcharged” rather than the intended conciliatory term). In the wake of Flight MH17 being shot down, Clinton has already said that the act of violence is a sign that Russian leader Vladimir Putin “has gone too far and we are not going to stand idly by.”

For most Americans, the failed wars in the Iraq and Afghanistan underscore the folly of unrestrained interventionism. So too do the attempts to arm rebels in Syria who may actually have ties to al Qaeda or other terrorist outfits. Barack Obama’s unilateral and constitutionally dubious deployment of American planes and then forces into Libya under NATO command turned tragic with the death of Amb. Chris Stevens and other Americans, and we still don’t really have any idea of what we were trying to accomplish there.

No one can doubt John McCain’s — or Hillary Clinton’s — patriotism and earnestness when it comes to foreign policy. But in the 21st century, America has little to show for its willingness to inject itself into all the corners of the globe. Neither do many of the nations that we have bombed and invaded and occupied.

Americans overwhelmingly support protecting Americans from terrorism and stopping the spread of nuclear weapons. They are realistic, however, that the U.S. cannot spread democracy or preserve human rights through militarism.

When the United States uses its unrivaled military power everywhere and all the time, we end up accomplishing far less than hawks desire. Being everywhere and threatening action all the time dissipates American power rather than concentrates it. Contra John McCain and Hillary Clinton, whatever happened in Ukrainian airspace doesn’t immediately or obviously involve the United States, even with the loss of an American citizen. The reflexive call for action is symptomatic of exactly what we need to stop doing, at least if we want to learn from the past dozen-plus years of our own failures.

President Obama is right to move cautiously regarding a U.S. response. He would be wiser still to use the last years of his presidency to begin the hard work of forging a foreign-policy consensus that all Americans can actually get behind, not just in this situation but in all the others we will surely encounter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com