When she left New York for good in early 2013 — retiring from show business and moving back to her home state of Michigan — it was as if some fundamental life force had suddenly disappeared from Broadway, like the demolition of a storied old theater or the closing of Mamma Mia. Elaine Stritch didn’t deny, in the few interviews she gave after she left, that she missed the city that she loved and came to embody. (“I’m about as unhappy as anybody can be” she told an interviewer last June.) And when she died on Thursday, at 89, it was perhaps a confirmation of what every New York theater lover already knew: neither Broadway nor Elaine Stritch could live without each other.

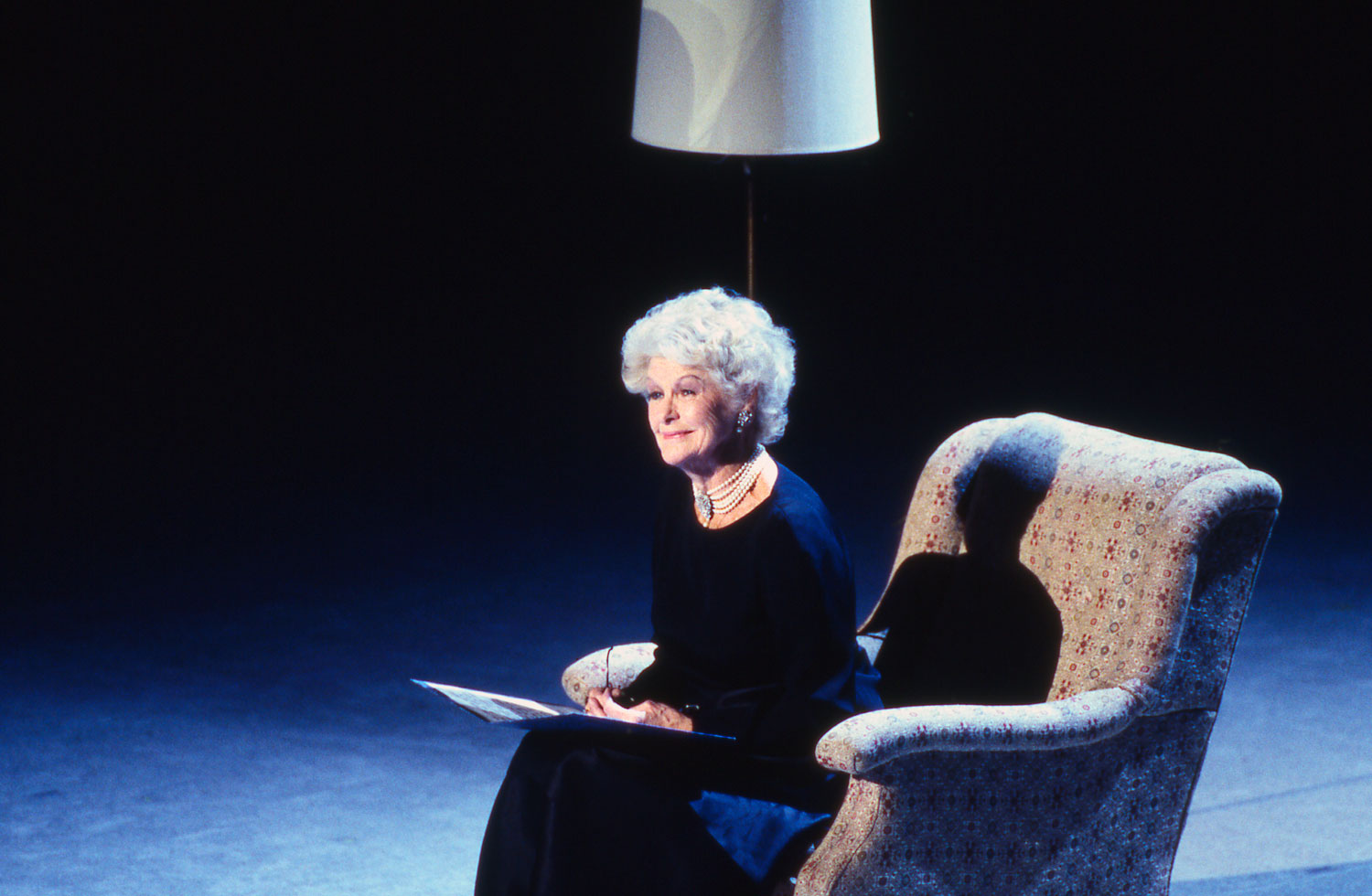

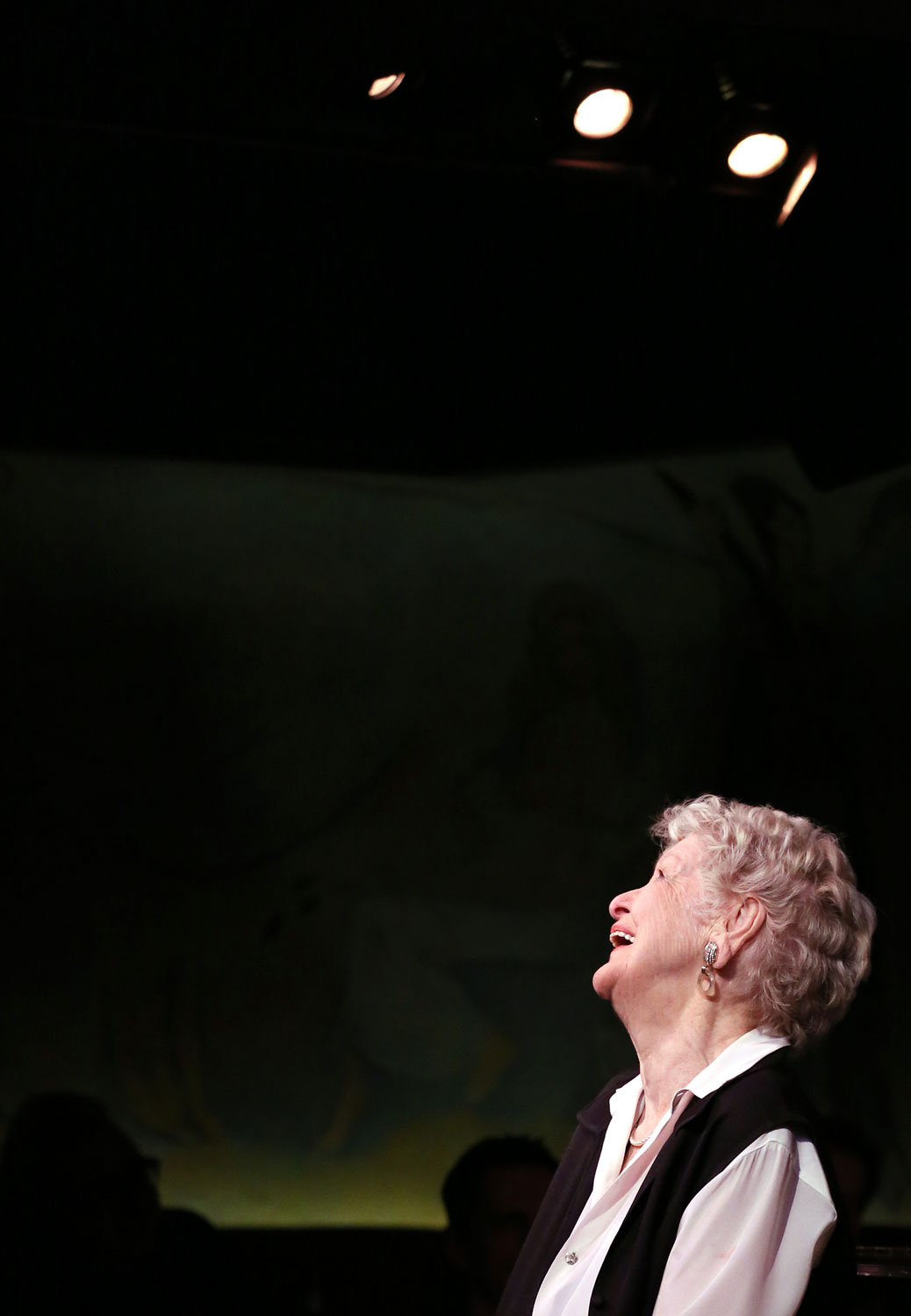

She was brassy (her name could almost define the word in Webster’s) and boozy, a salty broad with a gravely, gin-soaked voice bursting forth from an improbably pixie-like figure. Even in her late 70s, when she starred on Broadway in a one-woman show, Elaine Stritch at Liberty, she could show off her still lean and lithe gams in sheer black tights, and make you think that Broadway performers really are immortal. For many, she was.

“She was an indomitable spirit,” said Christine Ebersole, the two-time Tony Award winner who became close friends with Stritch in her later years. “I always felt really close to her — kindred spirits in a way. I admired her tenacity. She was a staunch character.”

Stritch was born in Detroit and began her Broadway career in the late 1940s. She understudied for Ethel Merman in Call Me Madam; sang one of Rodgers and Hart’s most scintillating comic numbers, “Zip,” in Pal Joey; starred in Noel Coward’s 1961 musical Sail Away; and replaced Uta Hagen as Martha in the original Broadway production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (a show, she later claimed, in which she experienced her first orgasm onstage).

But her career-defining turn came in Stephen Sondheim’s 1970 musical Company, in which she played a hard-drinking society dame and delivered her signature number, “The Ladies Who Lunch.” Stritch’s raspy voice and boozy defiance — “another vodka stinger!” — was the perfect match for Sondheim’s urbane cynicism, and she became one of his greatest muses and interpreters. A few years later she appropriated another Sondheim number as her own, his rousing anthem to show-business survival, “I’m Still Here.”

The song symbolized her own career, which seemed to keep hitting new heights as she aged. Woody Allen gave her juicy characters to play in his movies September and Small Time Crooks. On TV, she co-starred in the British comedy series Two’s Company and had frequent guest-starring roles in American sitcoms, most recently as Alec Baldwin’s hard-bitten mother in 30 Rock. She got a Tony nomination (one of five) for her co-starring role in the acclaimed 1996 Broadway revival of Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance.

She was 77 when she had her greatest role on Broadway — as herself in Elaine Stritch at Liberty, for which she won a Tony. She commanded the stage, delivering her signature numbers in between stories about her show-business career and her checkered personal life, from her romantic flings with stars like Marlon Brando and Rock Hudson to her blown audition for the starring role in the TV sitcom Golden Girls.

Backstage, too, she was reputedly a tough broad — always a big drinker, sometimes temperamental and insecure. Even at her last New York cabaret appearance — a farewell show at the Cafe Carlyle in April of last year — she berated the audience for interrupting her and laughing in the wrong places. But she was a Broadway diva who earned the right. She never gave less than her all, and the audience never gave her less than its unconditional love.

Elaine Stritch, Great Dame of Broadway

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com