The first step to capturing a Burmese python, Jeff Fobb tells me, is to grab it by the tail. “That’s away from the biting end,” he adds helpfully. Fobb is a dangerous-animal specialist with the Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Department. I’m at his home in the Miami suburb of Homestead to learn how to track and capture Burmese pythons, which can grow to more than 15 ft. (4.5 m). They choke their prey with powerful muscles and like to snack on raccoons, rabbits and the occasional small alligator. So when Fobb lets one of his training pythons loose in the warm Florida grass–cheerfully telling me that “fear is a natural reaction”–I dutifully grab hold of its nonbiting end and begin pulling it back toward the open.

I have just enough time to register a moment of pride in my mastery over this apex predator before the clearly annoyed python turns and strikes at my hands. I jump back. Burmese pythons aren’t venomous, but their rows of rearward-facing teeth can tear a chunk out of human flesh. It’s only with Fobb’s help that I’m able to corral the python, seizing the snake by the back of its skull. Just as we’re about to ease the python into a bag, Fobb gets a call–a boa constrictor has been found in an apartment in Miami Beach. While Fobb takes down the details, the waiting python constricts itself around my forearm, inflating like a blood-pressure cuff. As I begin to sweat in the sun, listening to the python’s insistent hiss, I’m left with one thought: I should not be here.

But then, neither should the python. Native to Southeast Asia, Burmese pythons began appearing regularly in South Florida more than 15 years ago. It’s likely that pythons brought in as pets had either escaped or were released into the wild, and then–like so many retirees before them–fell in love with the Sunshine State’s tropical climate. Today there may be as many as 100,000 Burmese pythons living amid the wetlands of South Florida, though no one really knows. Pythons can disappear when they want to, which is most of the time. During a monthlong state-sponsored hunt in 2013, nearly 1,600 participants found and captured just 68 pythons. Yet scientists have linked a drastic decline in small mammals in South Florida’s Everglades National Park to the pythons, which can lay up to 100 eggs at a time, grow more than 7 ft. (2.1 m) in their first two years and now face no natural predators. “Removing a huge portion of all the mammals from the Everglades is going to have a dramatic impact on the ecosystem,” says Michael Dorcas, a snake expert at Davidson College. “But right now we don’t have anything that can significantly suppress the python population.”

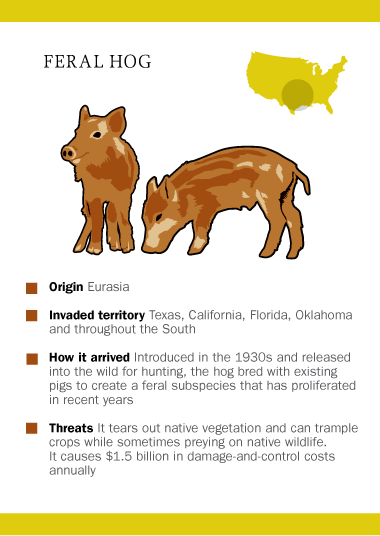

Burmese pythons have proved particularly successful invaders, but they’re hardly alone. On nearly every border, the U.S. is under biological invasion. A quarter of the wildlife in South Florida is exotic, more than anywhere else in the U.S., and the region has one of the highest numbers of alien plants in the world. While Florida is America’s soft underbelly when it comes to invasives, they are a nationwide problem. There are more than 50,000 alien species in the U.S., where they’ve often been able to outcompete–or simply eat–native flora and fauna. By some estimates, invasive species are the second biggest threat to endangered animals after habitat loss, and one study suggested that invasives could cost the U.S. as much as $120 billion a year in damages. In the Caribbean, lionfish scour coral reefs of sea life; in Texas, feral hogs rampage through farmers’ fields; in the Northeast, emerald ash borers turn trees into kindling; in the Great Lakes, zebra mussels encrust pipes and valves, rendering power plants worthless. On July 1, authorities at Los Angeles International Airport seized 67 live invasive giant African snails that were apparently intended for human consumption.

The problem seems to be getting worse–and we’re to blame. Most invasive species have been brought into the country by human beings either on purpose, in the case of exotic pets or plants, or accidentally, with alien species hitching a ride to new habitats. As global trade increases–during any 24-hour period, some 10,000 species are moving around in the ballast water of cargo ships–so does the chance of invasion. Add in climate change, which is forcing species to move as they adapt to rising temperatures, and it’s clear that the planet is becoming a giant mixing bowl, one that could end up numbingly homogenized as invasives spread across the globe. “The scale and the rate is unprecedented,” says Anthony Ricciardi, an invasive-species biologist at McGill University, who calls what’s happening “global swarming.” The balance of nature–an ideal state in which every species is in its right place–is seemingly being upended.

Given those fears, it’s no surprise that many conservationists treat invasives as enemy combatants in a biological war. The U.S. federal government spent $2.2 billion in 2012 trying to prevent, control and sometimes eradicate invasive species in an effort that involved numerous different agencies and departments. Yet there’s a small but growing number of biologists who question whether the war against invasives can ever be won–and whether it should even be fought. To these critics, nature has never been balanced, and there’s nothing that makes an alien species inherently bad or a native one inherently good. Human activity has so fundamentally altered the planet that there’s no going back, and we must learn to love–or at least tolerate–what the writer Emma Marris has called our “rambunctious garden” of a world. “The planet is changing,” says Mark A. Davis, a biologist at Macalester College. “If conservation is going to be relevant, it has to accept that.” And that means that the future could look a lot like South Florida.

The Great Exchange

Life has always been on the move, but until recently that mobility was limited by oceans, mountains and other geographic barriers. That separation allowed life to evolve into as many as 8.7 million separate species, if not far more. But then Homo sapiens arrived. As humans spread around the globe, they brought their favored plants and animals with them, along with stowaways like black rats, which originated in tropical Asia before infesting the planet from the holds of sailing ships.

For a long time there was little concern about the effects of introducing alien species to new ecosystems; they were sometimes even sought after. Thomas Jefferson wrote that “the greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add a useful plant to its culture,” and while he was an envoy in France he sent seeds of grasses, fruits and vegetables to botanists in the U.S.; he even smuggled home native rice from Italy. In 1871 the American Acclimatization Society was founded to bring “useful or interesting” animals and plants to North America, and the society’s president, Eugene Schieffelin, later released 60 European starlings in New York City’s Central Park, part of his dream to introduce every bird mentioned in Shakespeare to North America. He was all too successful: there are now some 200 million European starlings in the U.S.

It’s not surprising that the growth of invasive species has closely followed the growth of global trade. As canoes and clippers gave way to container ships and jumbo jets, it became easier and easier to move species around the globe. In her book The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert notes that before humans arrived in Hawaii, the islands experienced about one successful invasion every 10,000 years. Now Hawaii gets a new invasive species every month. Even falling political barriers make a difference. During the Cold War, the number of invasive bird species in politically isolated Eastern Europe fell while the number in the free states of Western Europe increased. “We’re absolutely seeing more invasions,” says David Lodge, a conservation biologist at Notre Dame. “The sheer speed at which things move around the planet gives them a much better chance to arrive alive, happy and ready to reproduce.”

Lodge should know. He has a front-row seat to the Great Lakes, one of the most heavily invaded freshwater ecosystems in the world. Since the St. Lawrence Seaway was opened in 1959, oceangoing vessels have been able to sail into the lakes, bringing alien species with them. That’s how the zebra mussel, one of the most tenacious aquatic invasives in the country, found a home in the Great Lakes. Native to southern Russia, the mussel arrived in the ballast water of ships and was discovered in the Great Lakes region in the late 1980s. There are now millions of the mussels in the lakes; clusters encrust anchors and docks and disrupt the marine food chain. Zebra mussels can grow so plentiful that they block the intake valves of power plants and industrial facilities, causing hundreds of millions of dollars in damage. “The mussels take all the plankton out of the water, pulling out the rug from under entire ecosystems,” says Marc Gaden, the legislative liaison of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

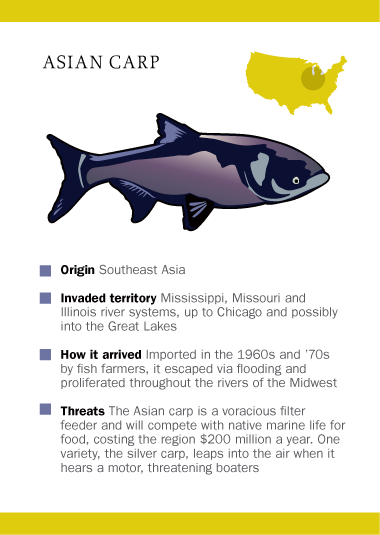

As destructive as they can be, zebra mussels are, in the end, mollusks–not the sort of charismatic invader that seizes public attention. But that’s not a problem for the Asian carp. First imported to the South and Midwest by fish farmers in the 1960s and ’70s, the Asian carp–a collective name for several related species from China–escaped at some point into the Mississippi River. In the years since, they’ve made their way upriver and are now knocking on the door of the Great Lakes. Bottom feeders, the carp could disrupt the marine food chain if they establish themselves in the Great Lakes, wrecking the region’s $7 billion sport-fishing industry. It doesn’t help that the silver Asian carp have a habit of leaping out of the water when startled by a boat motor, turning themselves into piscine projectiles that can clobber unwary fishermen.

The carp invasion has officials in the Great Lakes region so concerned that they are considering an Army Corps of Engineers plan–one that would potentially cost up to $18 billion–to essentially close the century-old Chicago Canal, cutting off the Great Lakes from the Mississippi River system. (Supporters of the plan have disputed the price tag.) Even so, it might be too late. Lodge and others have found genetic evidence that some Asian carp are already present in the lakes, although it’s not clear yet whether they are numerous enough to establish themselves.

The reality is that we already live in a deeply invaded world. Look out your window and you’ll see alien species everywhere. Kolbert writes that “almost all the grasses in American lawns come from somewhere else, including Kentucky bluegrass.” More than a quarter of the plants in Vermont and more than a third in Massachusetts come from outside those states. Baseball and apple pie might be American–unless the pies are made from Fuji apples, which were developed in Japan–but honeybees are not. (The scientific name–Apis mellifera, or European honeybee–is a giveaway.) More than 50 years ago, British ecologist Charles Elton, widely considered the founder of invasion biology, warned that “we are living in a period of the world’s history when the mingling of thousands of kinds of organisms from different parts of the world is setting up terrific dislocations in nature.”

There’s another name for that “terrific dislocation”: Florida.

The Mixing Bowl

Invasive plants and animals have flocked to Florida for some of the same reasons that more than 600 people a day move there: the sunny climate, the plentiful land and a generally welcoming attitude toward newcomers. And like many of the new human arrivals, invasive wildlife often enter the state through the sprawling hub of Miami International Airport, which ranks first in the U.S. in international freight shipments and live-animal traffic, with about 3,000 live-wildlife shipments every month. While border-control officials check cargo for invasive species, the sheer number of alien species entering Florida on any given day–and a climate that seems designed to turbocharge the growth of anything living–tilts the odds in the species’ favor. “We are ground zero for the impacts of invasive species,” says Doria Gordon, director of conservation science for the Florida chapter of the Nature Conservancy (TNC) . “And our invaders are very good at finding new habitats.”

Often those habitats are in or around the Everglades, that vast “river of grass” that covers much of South Florida. Half of the original Everglades has been developed for farming or housing, and the sprawling wetland has been carved up by more than 1,400 miles (2,250 km) of canals and levees that divert water for South Florida’s 5.8 million people. That mix of suburbs and wilderness makes the Everglades an invasive free-for-all. In the South Dade Wetlands, a small slice of protected territory about 25 miles (40 km) south of Miami, TNC’s Roberto Torres shows me thickets of Brazilian pepper trees thronging the sides of a canal. The pepper trees are beautiful, which is why they were imported as ornamentals from South America in the mid-1800s, but they’ve come to dominate more than 700,000 acres (280,000 hectares) of Florida, producing a dense canopy that shades out competitors. It’s one of dozens of invasive plants infesting the Everglades. “These plants outcompete natives and create a monoculture of simpler species where there was once diversity,” says Torres. “What kept them in check in their home territory isn’t here.”

And that leaves human beings. Florida has spent hundreds of millions of dollars trying to control invasives, work augmented by the efforts of ordinary people, like those who volunteer for the Python Patrol. Begun in 2008 when a python was discovered snacking on endangered Key Largo wood rats, the Python Patrol program has taught hundreds of Floridians to identify invasive snakes and lizards and capture them. It’s not easy work; pythons are ambush predators, waiting out their prey in hiding, and even experts will usually miss 99 pythons for every one they can see in the wild. But training a vast legion of people to spot and capture the pythons is just about the only way to control their numbers. Not that anyone has any idea exactly how many Burmese pythons are established in Florida. “There might be 4,000, and there might be hundreds of thousands,” says Cheryl Millett, a TNC biologist who helped run the Python Patrol before it was transferred to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “Either way, there’s more than there should be.”

Invasions in the Anthropocene

Invasion biology has become a sprawling discipline with its own journals, academic centers and graduate programs. But you can boil it all down to this dictum: the origin of species matters. Just because a plant or animal is alien doesn’t automatically mean it will become a dangerous invasive, but all else being equal, it’s best for nature if species stay at home–and it’s worth spending billions of dollars worldwide to prosecute a war against aliens. As the influential landscape architect Jens Jensen wrote in 1939, “No plant is more refined than that which belongs.”

To which Mark Davis asks: Who decided what belongs? In 2011, Davis and 18 of his colleagues made waves in the invasion-biology world when they co-wrote an essay in Nature that argued that conservationists should place less emphasis on the origins of a species than on how it acted in its habitat, wherever that might be.

They pointed to alien species like the tamarisk shrub, a drought-resistant plant from Africa and Eurasia that was introduced to the American West in the mid–19th century and eventually condemned as a water-stealing “alien invader,” becoming the object of a 70-year, multimillion-dollar eradication project. Yet it’s not clear that tamarisks use water at a higher rate than natives, and the plants provide nesting habitat for the endangered southwestern willow flycatcher.

The distinction between native and alien species is often arbitrary. To Davis and his colleagues, the “terrific dislocation” that biologists like Charles Elton decried is simply a fact of a globalized, human-dominated planet and is neither good nor bad. “It’s just not feasible in the current world to try to garden nature,” says Davis. “There is no wilderness, no place that hasn’t been touched by humans.”

The Nature article resulted in a swift backlash in the field, including an objection later printed in the journal that was signed by 141 conservation biologists. “It’s like climate change: 99% of experts will say this is a huge problem that’s getting worse,” says Daniel Simberloff, a conservation biologist at the University of Tennessee. “And then there’s a small fraction who are skeptical.”

In truth, though, Davis and his fellow renegades aren’t as far out as they seem. They don’t deny that some existing invasive species–like the emerald ash borer, an insect that has destroyed millions of U.S. trees–are worth fighting or that we should try to prevent invasions in the first place. But they’re right to argue that nativeness in and of itself has little intrinsic value. Native species can cause problems just as alien ones can, as TIME’s 2013 cover story on the rising populations of deer and other wildlife highlighted, and alien species can sometimes be better adapted to their new habitats than native ones are. (In recent years some chefs have even begun to specialize in invasive species, serving up Asian carp as “Kentucky tuna” and offering lionfish sushi.) “‘Natives,'” wrote the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould in 1998, “are only those organisms that first happened to gain and keep a footing.”

But even though the spread of invasives can actually lead to an increase in local diversity in absolute numbers–North America has an estimated 20% more species now than it did before European colonization–on a global scale, unchecked invasions can lead to planetary homogenization. Just as global trade has allowed megabrands like Walmart and McDonald’s to spread around the world, crushing local mom-and-pop shops, human activity has allowed “super species” like jellyfish and Argentine ants to invade new territory, displacing natives along the way. That’s fine from a purely evolutionary perspective–survival of the fittest and all that. But something will be lost if our planet becomes as homogenized biologically as it is economically and culturally. “If we had unlimited resources, we could try to stop this change,” says Davis. “But it’s just not possible to do.”

Human beings have become the dominant force on the planet, so much so that many scientists believe we’ve entered an entirely new geological epoch: the Anthropocene. We have already been shaping the planet unintentionally, through greenhouse-gas emissions and global trade and every other facet of modern existence. The challenge now is to take responsibility for that power over the planet and use it for the right ends–all the while knowing that there is no single correct answer, no lost state of grace we can beat back toward.

How we respond to the thickening invasions that we ourselves loosed will be a part of that answer–which is only just. There is one species that can claim to be the most dominant invasive of all time. From its origins in Africa, this species has spread to every corner of the world and every kind of climate. Everywhere it goes, it displaces natives, leaving extinction in its wake, altering habitat to suit its needs, with little regard for the ecological impact. Its numbers have grown nearly a millionfold, and its spread shows no sign of stopping. If that invasive species sounds familiar, it should. It’s us.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com