You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

To be a Kennedy is to lead two lives–the official one the family seeks with bright idealism and ruthless ambition, and the private one it tries to preserve behind the hedges of a seaside estate. But to be a Kennedy is also to understand how those two worlds can reinforce each other. Camelot stands not just for the elegant touches of the Kennedy presidency–an exhortation at the Berlin Wall, a journey into the hollows of Appalachia–but also for the carefully selected moments of the family at play. John F. Kennedy Jr. was urban royalty with a public conscience, a black-tie aristocrat who took the subway.

When a bullet has struck or a plane has crashed, Senator Ted Kennedy has been left to marry his family’s private tears to those of the nation. He has done it so often and so well that we remember him most fondly for the goose-bump lines in his eulogies; he shines brightest in the darkest suit.

Last week, when he again stepped up to a pulpit, this time to eulogize his nephew behind the closed doors of the Church of St. Thomas More in New York City, we could not hear the quiver in his voice. And we didn’t have to. It was there in the practiced cadences, the defiant wit, the stubborn Catholicism that insists on seeing all the way to the gates of heaven. “He and his bride have gone to be with his mother and father, where there will never be an end to love,” Kennedy said. And he promised that this family, at least, this old and bruised and sturdy family, would stand by in an eternal wake. “He was lost on that troubled night, but we will always wake for him, so that his time, which was not doubled but cut in half, will live forever in our memory and in our beguiled and broken hearts.”

But there is one thing he did not promise, and that’s what separated this day of mourning for the Kennedys from all the others. There was no rhetoric of the kind Ted Kennedy used at the 1980 Democratic Convention, when he said, “The dream shall never die.” A Kennedy friend who was there told TIME, “I’ve seen this family in other sad circumstances, and I’m telling you, this was different. This gang is shell-shocked, blown away. This wasn’t, ‘Let’s have 10 family members get up and say the torch is passed, time for a new generation.’ None of that. This was a funeral.”

On the day that he would help launch a frantic search for his nephew, Ted was leading a fight in the Senate for a more expansive Patients’ Bill of Rights. But by nightfall on that Friday, when no one in Hyannis Port had heard from John and Carolyn, it was Ted who called John in Manhattan, hoping he had not left. But he got only the voice of a friend whose air conditioning had broken down and who, at John’s invitation, was staying in his Tribeca apartment. Yes, John had left. No, he had not been heard from. The Senator reached Hyannis Port the next day and began the vigil. On Sunday, Coast Guard Rear Admiral Richard Larrabee switched to a search-and-recovery effort. This put an end to the hope that anyone would be found alive. Ted issued a statement of the family’s “unspeakable grief,” lowered the flag to half-staff and then went to the side of the person he knew would be suffering most.

He flew by helicopter to Caroline’s country house in Bridgehampton, N.Y., to comfort the niece he treats like a daughter over the loss of her brother, whom he loved like a son. There was a torch being passed after all. In the ’60s, Ted Kennedy’s generation orchestrated the death rituals. Now the old Senator was going to let Caroline, a member of the new generation, take charge. There were terrible decisions to be made, but not before Uncle Ted shot baskets with Caroline’s kids until they could be heard squealing with delight behind the hedge.

On Wednesday he climbed back into a helicopter for the return to Hyannis Port, where he took his two sons Teddy Jr. and Patrick, a Congressman, on a gruesome chore. Seven miles from shore, they boarded the salvage ship Grasp and then watched as three bodies were raised from 116 ft. under water. The cameras were far away, and Ted wore his dark glasses, but one picture captured the crumpled grief on his face. He had never looked so old.

Back in Bridgehampton, Caroline was calling the shots. She remembered how happy John had been to have engineered his wedding on Cumberland Island in Georgia in near total secrecy, and she wanted to make sure the ceremony marking his death would be no less private. So, with Ted’s help, she arranged to have John buried even farther from the mainland, his ashes and those of Carolyn and Lauren Bessette committed to the deep from the deck of an American warship. Seventeen relatives arrived at Woods Hole at 9 a.m. to be taken by the cutter Sanibel to the U.S.S. Briscoe, which had steamed up from Virginia overnight by special request of the Secretary of Defense. The only things those left onshore could see were the bright whites of the officials, the black of the mourners and a puff of smoke as the Briscoe motored out to the point at which the most powerful telephoto lenses could register just the silhouettes of the mourners. The family bore their loved ones’ ashes, three wreaths and three American flags. Caroline held her husband’s hand as he clutched a canvas bag. Red, white and yellow blossoms trailed the ship as it headed back to shore.

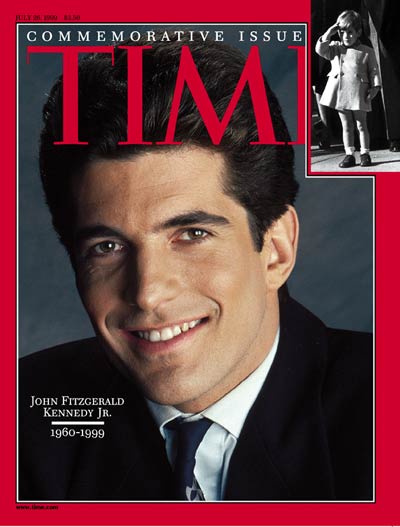

It seemed entirely right that the young boy with the salute should be buried by the Navy at sea, not far from the beach of Hyannis, where he and his father had built sand castles, and just west of the rocky shore of Martha’s Vineyard, where he had spent quiet summers after his father was gone. It would have been too much for the country to watch Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis bury her son, but she was there, nonetheless, in her daughter Caroline. “It was as if Jackie were orchestrating these ceremonies,” said Kennedy social secretary Letitia Baldrige.

Caroline was five years old when she clung to Jackie’s gloved hand at her father’s funeral. Jackie had known that her black veil and a riderless horse were right for the slain President. So when it came time to think about how to lay her brother to rest, Caroline sensed that she should take her brother to sea, not to a plot at Arlington National Cemetery, and not to a cemetery that might be transformed overnight into another Graceland.

She was also determined to keep the family’s deliberations–and its sorrow–out of view. When she found out that someone from the family was offering reporters details of life inside the compound, she asked Ted to shut that down. One of John’s closest friends, former Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow, said he “paid dearly” for appearing on TV. Though he’d already booked a flight from New Orleans to New York for the memorial service, he pointedly wasn’t invited.

Some reports said Ted, as curator of the Kennedy political legacy, had urged a service that would satisfy the public need to say goodbye–something in a cavernous cathedral befitting cardinals and Presidents–even if the sad truth was that a piece of the dream had died for him this time. “You could just see this was a father-son relationship,” said Senator Alan Simpson. “I’m sure it’s ripped the very fabric of Ted’s life.” John was the little boy Ted imagined could grow up to be President. He’d taken John under his wing from the moment his father was killed, staying in the White House after the Kings and Prime Ministers and generals had left, to celebrate John’s third birthday. He had led the singing of Heart of My Heart late into the night.

Caroline chose St. Thomas More, a small, neighborhood Roman Catholic church a few blocks from their mother’s Fifth Avenue apartment, where she and John had gone to Mass as children. Despite reports of family friction over the choice of venue, a source familiar with the arrangements told TIME, “From Day One, it was always going to be at this church.” The church, with its English pastoral, beige-stone sanctuary, is plain, and for the ceremony it was furnished simply. Two white hydrangea flower arrangements sat on either side of the altar on the floor. To gain access, almost every guest–from Senators to George magazine staff members to Kennedy White House veterans–had to show an invitation about the size of an index card with the guest’s name printed on it. The family was so set on privacy that not even the church staff could attend the service.

On Thursday the Senator stayed up past midnight working on his eulogy and, after flying from Hyannis Port to New York, polished it at his sister Pat Lawford’s apartment. Plans were so last-minute that when staff members turned in for the night, it was still unclear whether Caroline would speak; the program was not printed until 1 a.m. It was her decision to ask Ted to deliver the eulogy. But even if she didn’t eulogize John, it was she and her children who became the emotional center of the service. She reminded the mourners about the love of literature that her mother had bestowed on her and John, and then read Prospero’s speech from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, a play in which he had performed. It was an acknowledgment that her brother had lived on a big stage but had understood that its “insubstantial pageant” would fade. “We are such stuff as dreams are made on,” she quoted, “and our little life is rounded with a sleep.” There were muffled sobs as Caroline’s husband Edwin and her children Rose, 11, Tatiana, 9, and John, 6, lit candles and hip-hop artist Wyclef Jean sang, “It was time for me to go home/ And I’ll be smiling in paradise,” from the Jimmy Cliff reggae song Many Rivers to Cross.

There were also tears down mourners’ faces when fashion-industry executive Hamilton South, in his eulogy for Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, praised “her graceful bearing, her special allure” as “a physical expression of an inner fact.”

But Caroline was the focus of the service’s most wrenching moment. Ted came close to breaking down when he reached the part in his eulogy that celebrated the closeness between her and John, the brother who, even as a grownup, would reach out naturally to grab his sister’s hand. “He especially cherished his sister Caroline,” Ted said in his eulogy, his voice trembling, “celebrated her brilliance and took strength and joy from their lifelong mutual-admiration society.” Caroline stood up to hug her uncle as he descended from the pulpit.

The memorial service was a somber reminder that for patriarch Ted, the grandest unseen achievement has been in finding a way to be a genuinely loving presence in the hearts of so many Kennedy children left fatherless. Weddings, graduations, birthdays, christenings–Teddy is always there with his booming voice, his animal imitations, his begging anyone who can pick out a tune at the piano to keep the music going. He gave Caroline away at her marriage to Edwin Schlossberg in 1986, and when it was all over, Jackie hugged him on the steps outside Our Lady of Victory on Cape Cod and beamed, as if to say what a job we have done. He toasted John at his intimate island wedding in 1996. He took John and Caroline on rafting trips. He kept vigil with them at the bedside of their mother, who succumbed to cancer at 64, and gave a eulogy at that funeral.

With such a large family, it has been a miracle that he could be so many places at once. On the day he gave away in marriage his brother Bobby’s daughter Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, he went to the hospital where his eldest son Edward had had a cancerous leg amputated. Soon after, the Senator went skiing with young Teddy, who quickly took to the slopes on one leg. When Teddy beat him to the bottom of the hill, the Senator made a fast turn to spray the boy with snow while wiping away tears. Last Friday, at the reception following the memorial service, it was Kennedy again who helped lift the spirits of those around him. He told stories and jokes, and found his voice to sing the hymn Just a Closer Walk with Thee.

As he rose to the occasion one more time, Ted became the public man his elder brothers would have been proud of and the private one that untimely deaths in his family have required. Whether from too much tragedy or too little character, for a while every good thing Ted did was erased by a bad one like Chappaquiddick. But when he married Victoria Reggie in 1992, he found a partner who would change his life.

He now drinks club soda and runs off during the Senate’s official dinner window to be with his stepchildren Curran, 16, and Caroline, 13. He’s a constant presence at their plays and sporting events, and has even been known to get personally involved in pulling a loose tooth.

If his private life is shaped by his love for children and stepchildren, his public one is still shaped by his concern for the little guy, the one who parks your car, rings the cash register at the convenience store, catches the early bus. As he left town he was trying to expand health care, and when he comes back from burying his nephew, he will be fighting to raise the minimum wage. Leaving the Coast Guard cutter that brought the family and friends back to Woods Hole after the burial, he shook hands formally with the officers in their dress whites but gave the crewmen in working blues a slap on the back. It was a gesture that surely would have made his nephew smile.

—With reporting by Melissa August and Ann Blackman/Washington

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com