Syrian artist Hrair Sarkissian was only 12 years old when he saw three hanged bodies dangling in the middle of a public square while on a bus to school in his native Damascus. Years later, he says, the image of the dead still haunted him — and in the hopes of overcoming the memory’s hold on him, he decided to photograph the place where it all started.

Sarkissian, who is currently based in London, took a series of photographs called Execution Squares, shooting spaces in the Syrian cities of Aleppo, Lattakia and Damascus where criminals had been routinely hanged before the uprising against Bashar al-Assad began in 2011. The photographs show locations one would expect to find in urban environments, yet the apartment buildings, billboards, and empty streets depicted feel heavy with the presence of death — the corpses are long gone, but viewers are left to imagine where they might have hung. Each image juxtaposes the constancy of the physical location where it was taken with the fluidity of real life events — in this case, capital punishment — situated within shifting social, political and ethical contexts.

Sarkissian’s work is now being displayed at the New Museum in New York as part of an exhibition that celebrates the work of 45 artists of Arab origin. The exhibit, titled Here and Elsewhere, is the first museum-wide show in New York City to exclusively feature art from and about the Arab-speaking world, showcasing layers of Arab identities often imperceptible to or simplified by Western audiences. Some of the questions posed are ones Sarkissian himself is trying to answer: Can artists use their work to chronicle real-life events, positioning themselves as witnesses to historical changes? Or should they be asking themselves and their audience whether images can accurately capture reality in the first place?

“I was relying on photography to show me the truth — that these bodies don’t exist anymore in these squares, to convince me they are all erased,” Sarkissian tells TIME. “But it didn’t convince me. I still see the hanged bodies in these empty squares.”

Massimiliano Gioni, Associate Director and Director of Exhibitions at the New Museum, explains that the show examines the act of representation, of experiences both individual and collective, with an eye to “what is at stake” when images are created and disseminated. While some artists in the show use their work to oppose the existence of a single historical truth, others aim to showcase the process behind constructing a point of view, and a few revise narratives that dominate in the public sphere. The exhibit’s title comes from a 1976 film by French directors Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Gorin, and Anne-Marie Miéville, which Gioni noted was originally meant as a propaganda tool about the Palestinian struggle for independence, but was eventually transformed into “a reflection on how images are constructed and used to convey ideologies.”

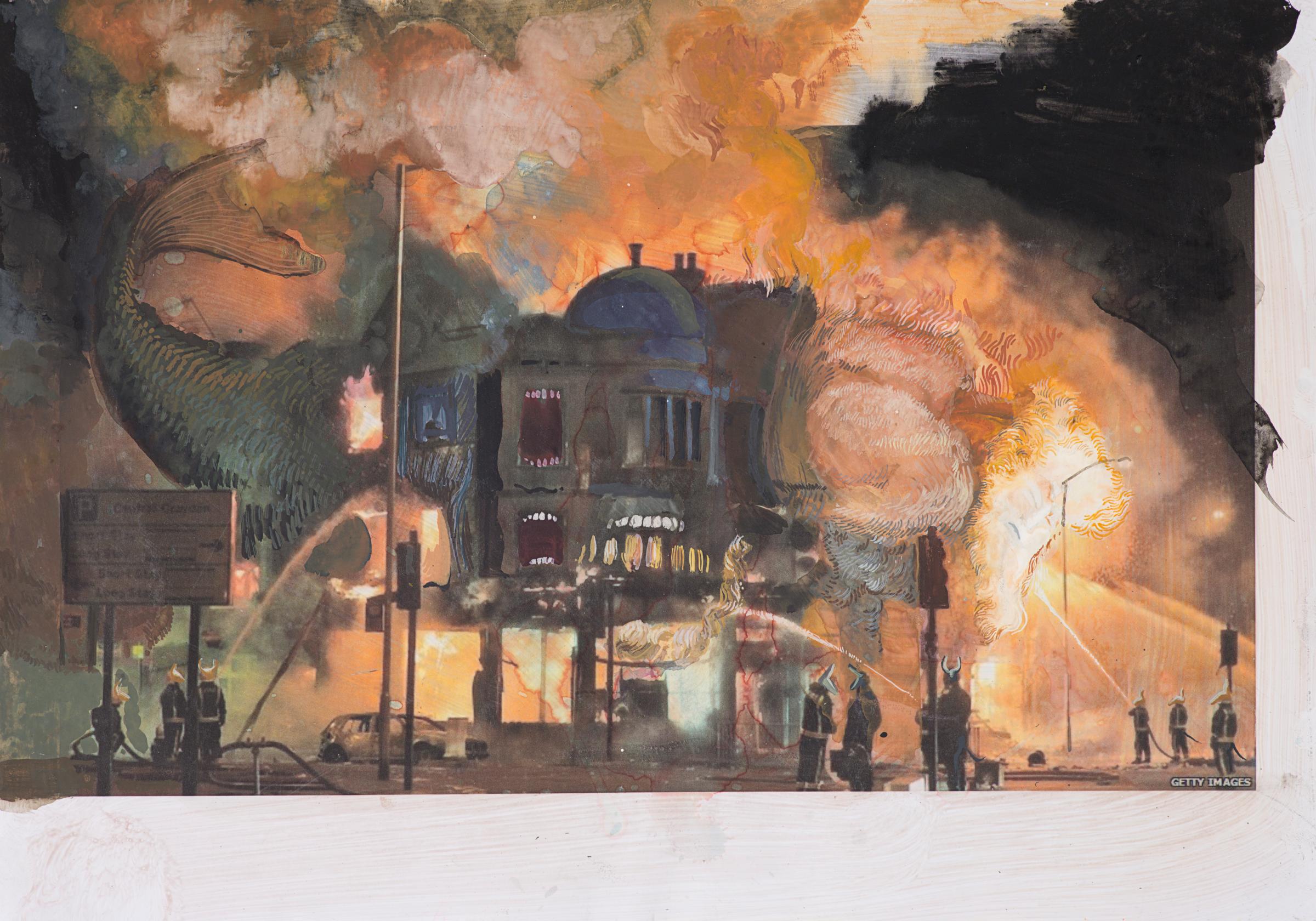

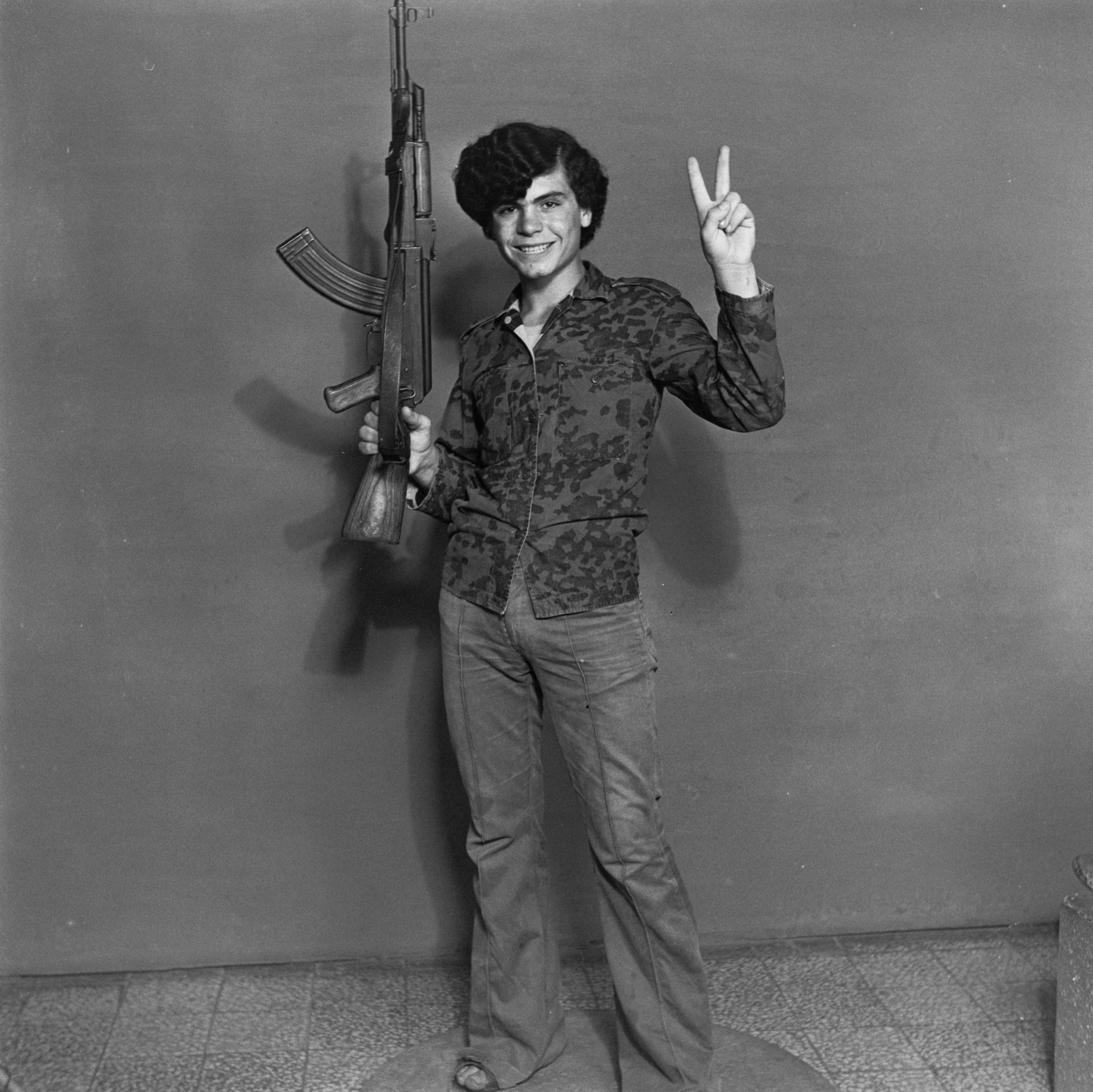

One artist, Iranian-born Rokni Haerizadeh, transforms documentary footage into allegory by printing stills from YouTube videos of media broadcasts, then painting over them, molding the subjects — including policemen, politicians, protestors, and bystanders — into distorted Orwellian hybrids: half-human, half-animal. Another contributor, an anonymous Syrian collective of filmmakers called Abounaddara, creates short films that document events currently unraveling in their home country — ranging from intimate human interactions to violent fights in the streets — in the hopes of distributing an account different from the one common in mainstream media. “We associate photos and videos with transparency and the truth,” Gioni says, “yet these images… are much different from what we see on TV.”

The poignancy of Abounaddara’s work is derived partly from the group’s modest means of creation. Whereas artists in New York usually spend a lot on art supplies, Gioni explains, this exhibit showcases art that “[was] made with a pen, pencil, paper, a camera… but is equally intense.” Beirut-based Rheims Alkadhi, for instance, found artistic value in items impoverished residents have been forced to sell in street markets — a polyester jacket thus became the subject of The smell of an urban people in the lining of a jacket, and pieces of hair from the hairbrushes of Palestinians constitute part of her project Collective Knotting Together of Hairs.

“A lot of this work is maybe less appealing from a commercial point of view, and perhaps not [the kind of art] that is fashionable in New York — a lot of it is more content-driven, which makes it fascinating,” Gioni says. “What sets apart this type of work is that it’s vested in issues that are bigger than the price of an artwork and whether an artwork looks good on the wall. It is instead vested in issues of life and death, in important social and historical transformations.”

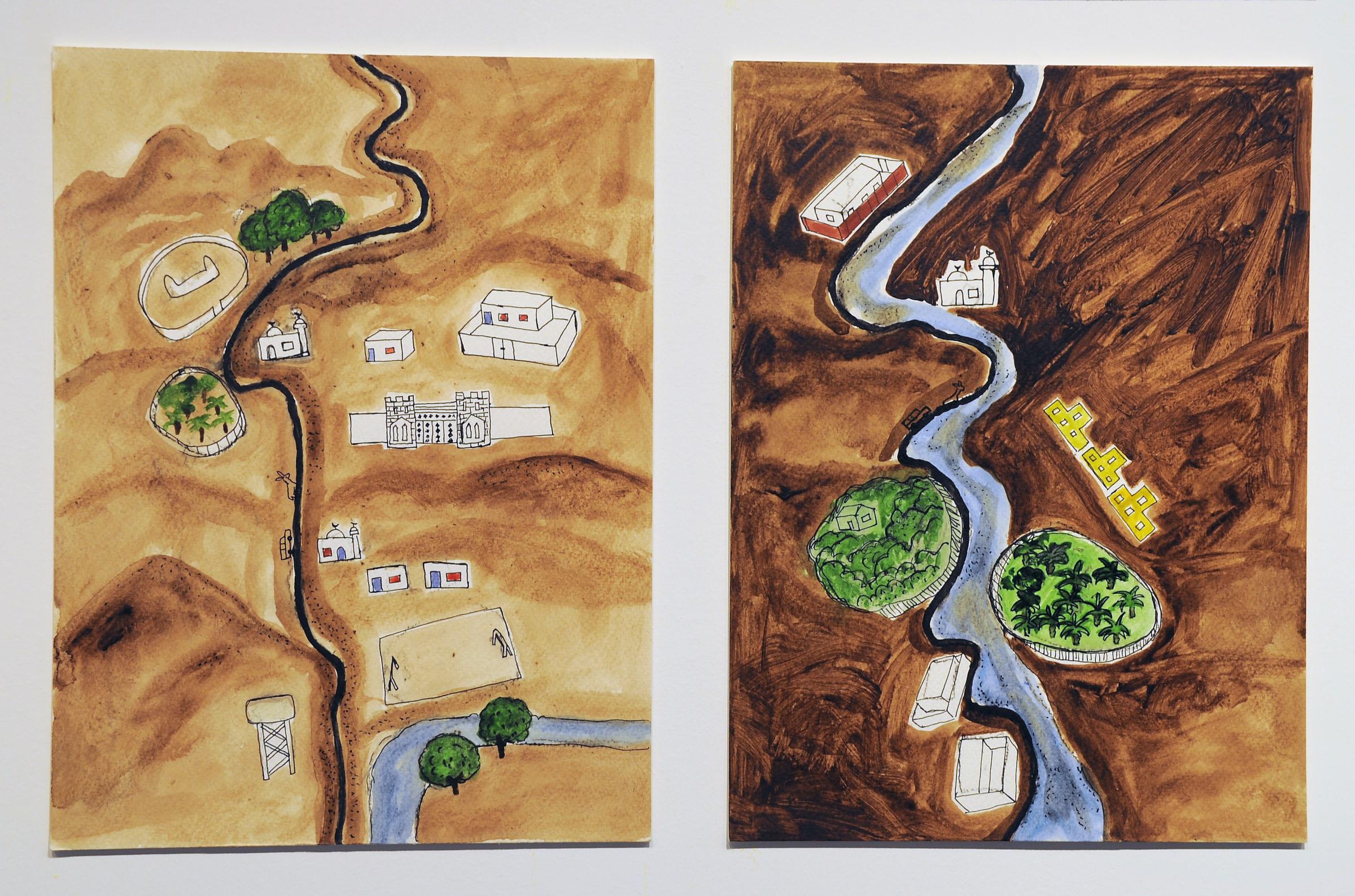

But Gioni and Curatorial Associate Natalie Bell were careful to point out that the show was not conceived as a vehicle for documenting current unrest in Arab countries. Sarkissian, too, emphasized that his photographs “have nothing to do with what is happening now in Syria; executions happened everywhere, and it’s more about humans and how we perceive that act.” Gioni notes that even Cairo-born Anna Boghiguian’s drawings created in the midst of the 2011 uprisings in the Egyptian capital that led to the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak are a blend of “the world out there and the internal, psychological world of the artist.” There is no pretense of objectivity in her work, he says, resulting in a “sincere” representation.

Ultimately, the exhibit attempts to deny the existence of a particular style connected to the region — and it succeeds in that aim, as curators’ attitudes in choosing and placing the artworks haven’t been simplistic or colonial: organizers have instead insisted on preserving the multiplicity of views that exist within the Arab-speaking world. An additional reason the museum has taken extensive care to avoid stereotypes is that some American viewers may be encountering contemporary art from the Arab world for the first time. With many of the exhibition’s artists living in international locations and never before having shown in New York, its nod to art’s global ramifications is clear.

“A lot of this kind of work was not being shown in New York, and it was time to show it [here], in a more institutional context.” he says. “I hope the exhibit will remind us to train ourselves to keep our minds and our eyes open, so that we are not preoccupied with only our ‘here’ but also with ‘elsewhere.’”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com