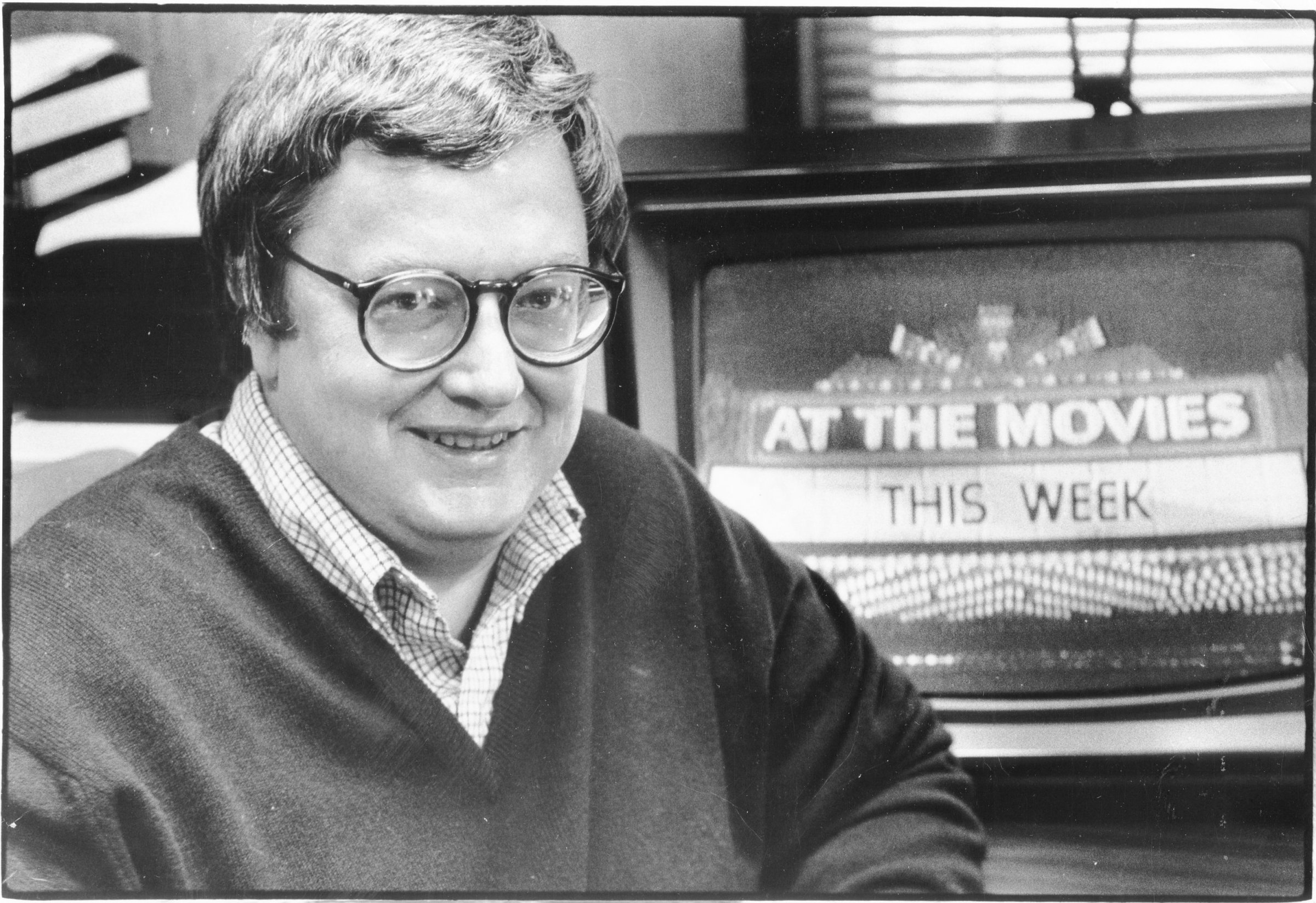

The time it takes to make a documentary film may vary, but Steve James’ work on Life Itself had a limited timeline. The Hoop Dreams director began filming in December of 2012; his subject, the legendary critic Roger Ebert, died of cancer only a few months later, in April 2013. (James says that he believes he took the last-ever picture of Ebert. The film, which is named after Ebert’s memoir of the same name, arrives in theaters on July 4.) And, despite its title, James says the film — as a result of its timing — is in many ways more about death than about life.

“I like to think he shows us how to die,” says James. “And how to do it with tremendous grace and generosity.”

James says that he knew from the beginning that, though the documentary intended to address Ebert’s effect on film culture — TIME’s film critic Richard Corliss is among the interviewees, and he wrote about Ebert for the latest issue of the magazine — and his critical career, it wouldn’t just be about Ebert at the movies. Rather, just as his life influenced his critical opinions, his fame as a critic would be a way to talk about the rest of his life. The key, James says, is that Ebert had learned how to embrace life, struggles and all, and to let that love inform his work — and, eventually, his death.

James says that Ebert was initially reluctant to share some of the grittier facts of his physical decline. When he first had jaw surgery that left his face disfigured, James notes, he kept an old photo of himself as the image on his website; he finally revealed his new face in a 2011 blog post that James says was a result of deciding that he didn’t want to hide anymore, a decision that would come to define what many remember about him. Even people who weren’t film buffs looked to him as an example of someone confronting illness and death head-on. As Life Itself (the film) points out, Ebert’s colleague and professional rival Gene Siskel died in the late ’90s after having been extremely private about the progression of his own cancer. Ebert’s feelings about Siskel were complicated, but the secret illness and sudden death were shocking; after seeing Siskel make that decision about how to die, Ebert went the opposite direction.

Even so, with the world clued in to his illness, allowing a camera into his hospital room took extra guts. “[Being open about his illness] was what made him more than a film critic to a lot of people,” James says. “There’s a level of candor there that was courageous, but it wasn’t the same as inviting a film crew into a hospital room and seeing him get suctioned.”

As Ebert’s health declined even further, while James was still working on the movie, the critic’s candor gave way to doctors’ demands to keep him away from distractions. When he returned to the hospital near the end of his life, they didn’t want to tire him out with filming, and James says that he agreed that — when it was clear that the critic’s energy was failing — they had reached the point where openness gives way to a family’s need for privacy. And besides, James says, there’s a reason why the balance of candor and discretion ended up just where he wanted it: his subject was uniquely qualified to know what needed to be seen on camera.

“I think he realized that if he was going to have a documentary made about himself,” James says, “he wanted it to be a documentary that would be the kind of documentary he would want to see.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com