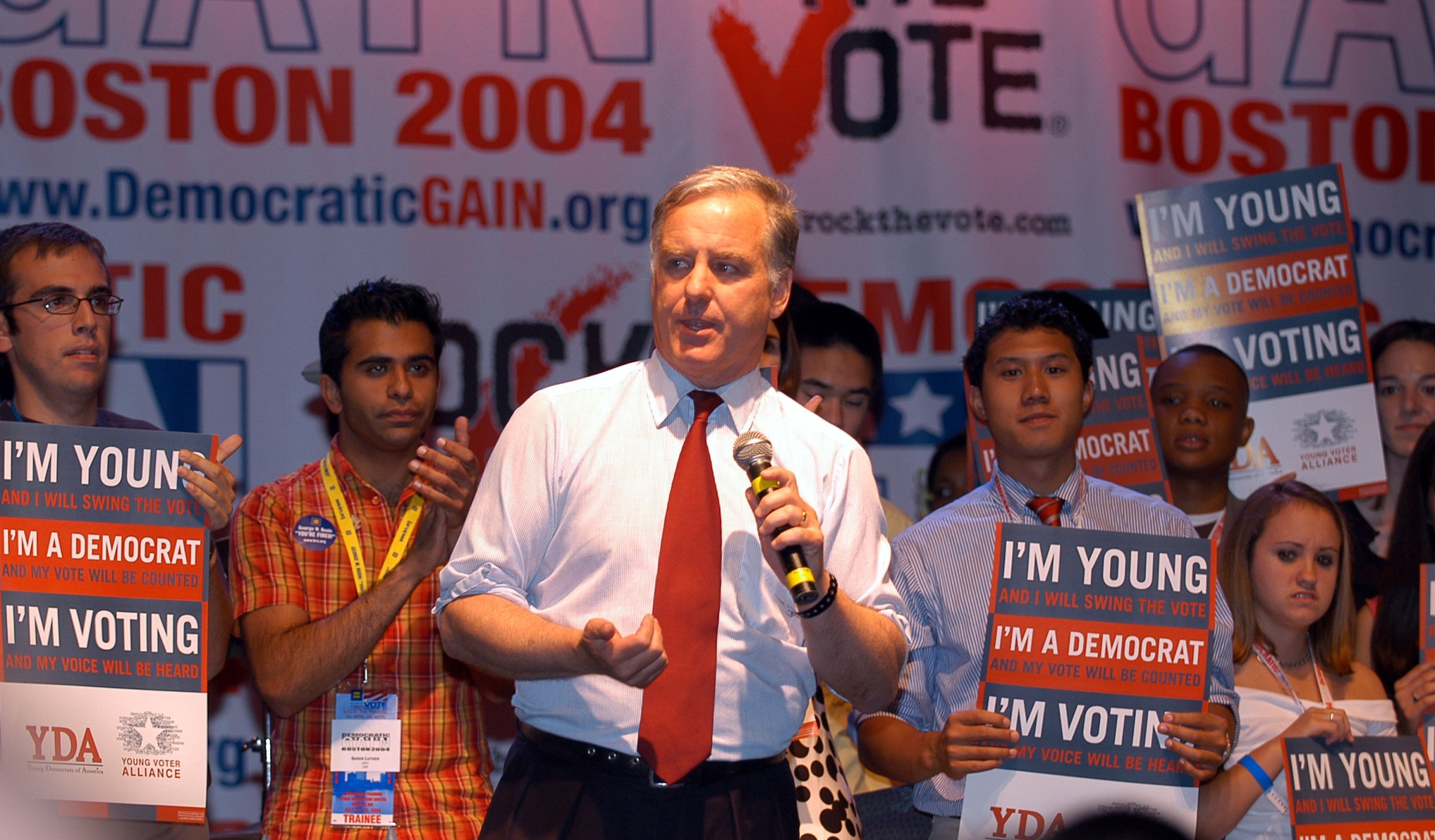

When former Vermont governor Howard Dean announced his long-shot campaign for President 11 years ago, he changed the way campaigns work.

And though he didn’t win, without Dean, the next Democratic campaign—the one that elected Barack Obama—would have looked very different. Now, with 2016 on the horizon and the evolving role of big money threatening to permanently relegate ordinary people to mere window dressing in our political process, the Dean effort offers an important lesson to anyone who cares about the future of our democracy.

When I tell people I worked for Howard Dean’s presidential run, they often seem proud to know a bit about a campaign that has mostly been relegated to trivia: “That’s the guy who lost because of the scream, right?”

The truth is that Dean had already come in a disappointing third in the Iowa caucuses that day, before the scream happened. So we were most likely already done.

But the Dean campaign did not lack for passionate and widespread support. He led national polls heading into Iowa, and built the biggest lists of offline volunteers and online donors in the field. It was the first campaign of the digital era that truly opened itself up to collaboration: to bloggers, to software developers, to volunteers creating their own groups online and offline in communities across the country. And because of the candidate’s willingness to say things that other candidates wouldn’t, even if they agreed—that the war in Iraq was a bad idea, that every American should have health insurance, that the politics of fear and division and mealy-mouthed calculation do a disservice to our political process—people joined.

So, what happened? Put very simply, the campaign organization—we, the staff—let these people down. Those grassroots supporters did what they were supposed to do: they recruited their friends, donated $5 and $10 where they could and showed up to volunteer where we asked, when we asked. But the energy of those people overwhelmed the campaign’s capacity to use it effectively. The campaign organization failed to connect that money and those efforts to the mechanics of winning in Iowa—or anywhere else.

This failure loomed large when, four years later, I was asked to put together a digital strategy for Barack Obama’s improbable campaign for president. I had already seen the glimmer in the eyes of people who hoped he’d run. It would be such a shame for our party, and in a fundamental way disappointing for our democracy, if another campaign with genuine grassroots energy and the possibility of bringing new people into the political process failed to channel it into victory.

It took less than a day on the job to discover that the Obama organization would be different: crisply decisive, metrics-driven and with a clear understanding that building a nationwide grassroots movement very quickly would be its only path to victory. The digital campaign would be at the heart of it, and we built something bigger and better than we could have imagined back in Burlington. And there were other Dean veterans like me who went into the Obama campaign with something to prove, like Jeremy Bird, who built a grassroots field organization in South Carolina during the primary based on the notion of community organizing—something he and the Dean team had piloted in New Hampshire in 2004 in one of the too-few pockets of promise. Their work became irrelevant after the catastrophe in Iowa dug a hole too deep.

The Dean campaign was a wake-up call for me about the importance of disciplined organization in our political process, and a reminder that narratives about what’s happening in an election can be upturned at any time by organizational realities and the flawed human beings who make decisions (or don’t) in the heat of a campaign.

The job of the campaign staff is to shape the limited time and activity of both the candidate and his or her supporters into a unified effort that drives a win.

It’s tempting to think of the candidate as the CEO of a campaign, but the responsibility for making the pieces of a campaign work falls to the staff. This is as it should be; it’s depressing to think of skilled political campaign management as a prerequisite for our elected leaders. A great campaign is one that channels the candidate’s best attributes and honors the time and money of those willing to give it to the cause.

In that sense, we let down Howard Dean, too. But he kept going: he took the thankless job of party chairman and doggedly pursued a 50-state strategy that opened up the institution to grassroots organizing, made data and infrastructure a top priority and put small donations back at the core, re-energizing the party in unlikely places and laying the foundation for the Democratic midterm sweep in 2006 and, of course, 2008.

Even beyond that record, the candidate himself remains an inspiration for the same reasons I went to work for him a decade ago: unwavering authenticity, persistent indignation and a willingness to run a campaign like you’ve got nothing to lose.

I wish we could have given him a win. But I know I and many others—perhaps even Dean himself—were shaped and sharpened by that loss, and in that way his campaign for president has done more good for our side than any of us could have imagined a decade ago.

Joe Rospars is Co-founder & CEO of Blue State Digital and was the principal digital strategist for both of Barack Obama’s presidential campaigns. He got his start as a writer on Howard Dean’s 2004 campaign, over a decade ago.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com