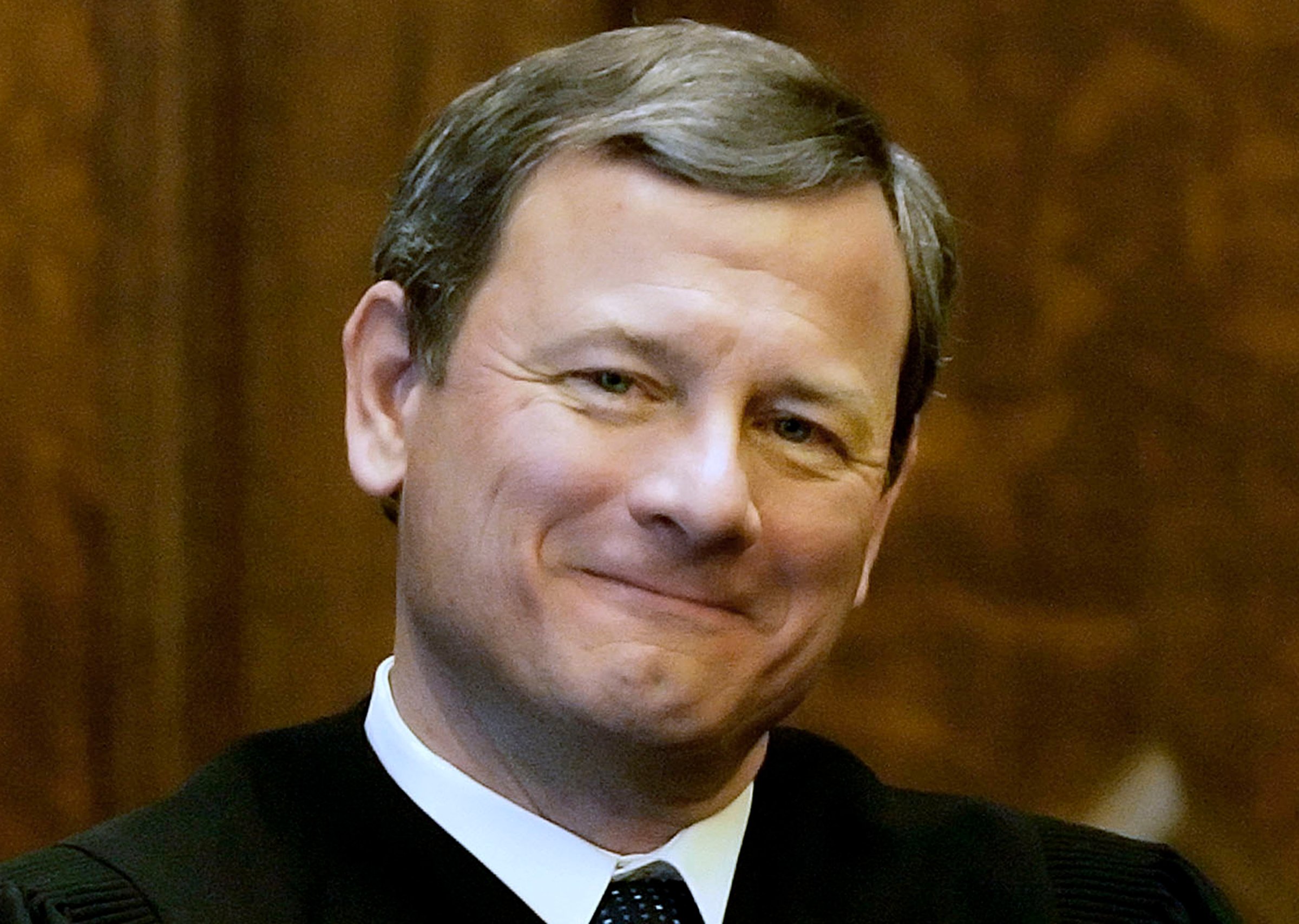

Nine years into his service as Chief Justice, John Roberts may finally have shaped the nation’s highest tribunal into a “Roberts Court.” The term that ended on Monday was a reflection of goals that Roberts set during his 2005 confirmation hearings—more unanimous opinions, for example, and a more modest idea of the Supreme Court’s role in society.

Despite two 5-to-4 splits on the final day of term, in cases involving union dues and the Affordable Care Act, the Roberts Court delivered unanimous opinions in more than 60 percent of the cases decided this year, the highest percentage in decades. That doesn’t happen by accident. As the eminent Constitutional authority Lawrence Tribe of Harvard Law School has noted, a number of these 9-to-0 opinions contain significant disputes just beneath the surface. The Roberts Court is placing high value, in a time of polarized government, on finding common ground in spite of real philosophical differences.

And there was something distinctive about those 5-to-4 calls on the final day, as well. Faced with sharp splits that could not be papered over, Roberts assigned the same associate justice to write both of the opinions: Samuel Alito.

Alito is a fascinating judge—that is, if modesty and predictability happen to fascinate you. Arguably the purest conservative on the Court, Alito disdains the sort of flashy, rhetorical disagreement perfected by Antonin Scalia and former Justice John Paul Stevens, the dueling dissenters of the earlier Rehnquist Court. His Monday rulings reflected both his conservatism and his judicial modesty. In a case challenging the power of public employee unions to impose fees on non-members, Alito’s opinion went against the union. But he stopped well short of the sweeping blow that anti-union politicians and pundits were hoping for.

Likewise, in a case asking whether the owners of private corporations can be forced to provide contraception methods that offend their religious beliefs, Alito anchored a majority in favor of the owners. But his opinion was hedged throughout. Questions of how the ruling might apply to publicly traded corporations, or whether it might apply to other religious convictions, were left for another day.

In 2005, Roberts famously compared this narrow approach to a baseball umpire calling balls and strikes. The umpire is not making a blanket ruling covering every conceivable pitch. The idea is to frame a strike zone and apply it consistently on a pitch-by-pitch basis. The fact that Alito wrote both of the last-day opinions suggests that he’s the justice that Roberts wants behind the plate on the close calls. This matters because the Chief Justice has so few powers, and one of the most important is that when the Chief is part of the majority, he gets to choose the writer.

By such small increments, change comes to the Supreme Court. It is, by its nature, a slow-moving institution. And the Chief Justice is the least powerful of the leaders of the branches of American government—just one of nine voices, all with an equal say in which cases the Court will hear and how they will be decided. But step by step, opinion by opinion, Roberts is stamping his image on the institution. The term that ended on Monday put us clearly into the Roberts Court era.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com