The biggest obstacle for states trying to execute death row inmates seems simple enough to overcome. But obtaining lethal injection drugs has turned into an existential crisis for the country’s most modern method of capital punishment.

Oklahoma announced Tuesday that it was delaying two upcoming executions after it failed last week to get two of the three drugs it planned to use to execute a pair of death row inmates. In a brief filed Monday with the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, the state’s assistant attorney general said Oklahoma does not have supplies of pentobarbital and vecuronium bromide.

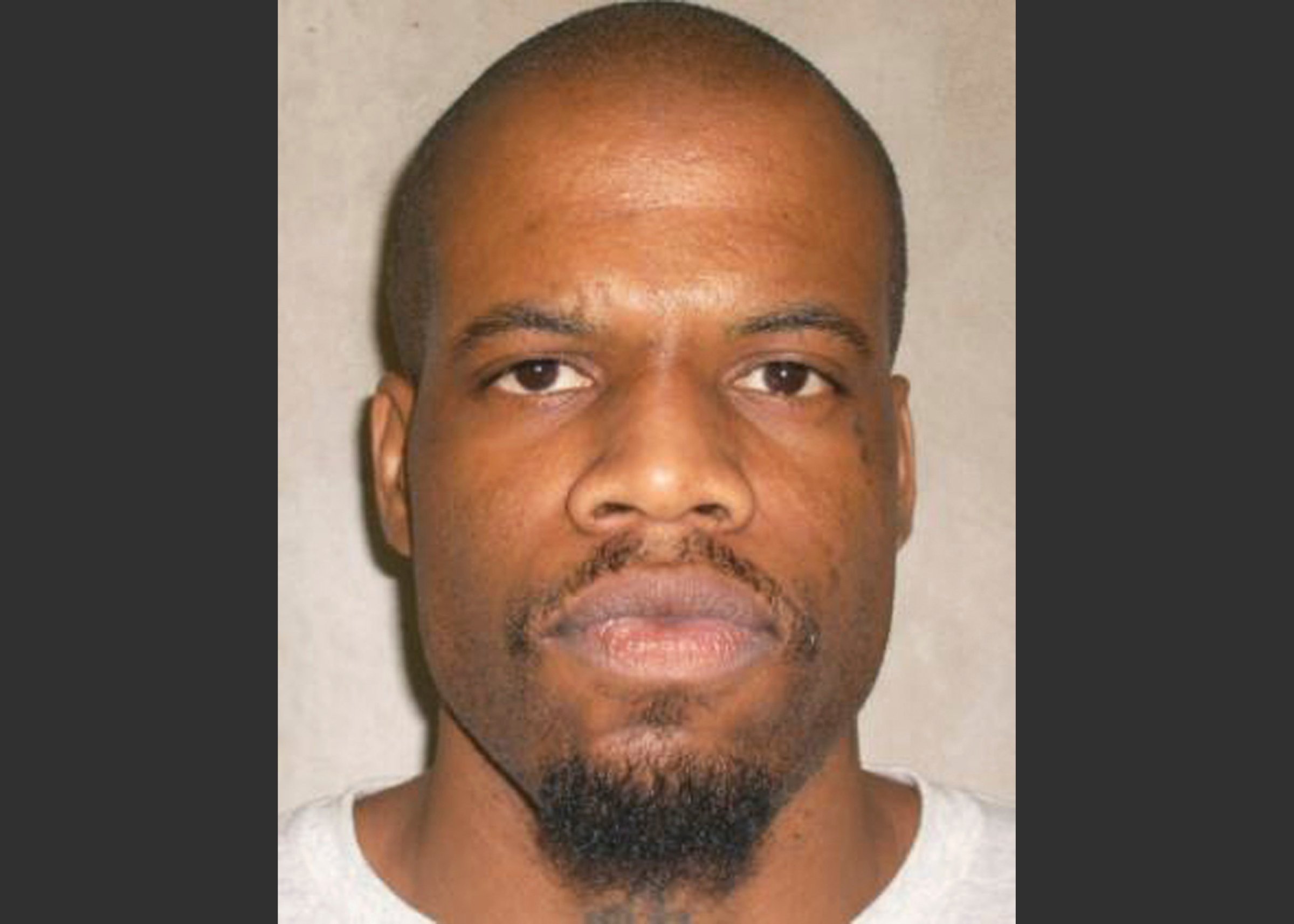

“This has been nothing short of a Herculean effort, undertaken with the sole objective of carrying out ODOC’s duty under Oklahoma law to conduct Appellants’ executions,” wrote Assistant Attorney General Seth Braham, referring to the Oklahoma Department of Corrections and the planned executions of Clayton Lockett, originally scheduled for Thursday, and inmate Charles Frederick Warner, initially slated to die March 27. Both inmates’ execution dates have been postponed, but it’s unclear how the state plans to obtain the two drugs it currently lacks.

States around the country are struggling to administer lethal injection death sentences after a number of pharmaceutical companies have denied them drugs. Many states have turned to unregulated compounding pharmacies, which has triggered a series of lawsuits from inmates. Because many corrections departments have tried to keep compounded pharmacies’ identities anonymous, death row inmates argue that without knowing where execution drugs are produced, it’s impossible to know if they’re manufactured in a way that would produce a humane execution and therefore be constitutional.

In January, Oklahoma inmate Michael Wilson was executed with a three-drug protocol that included pentobarbital. Soon after the execution began he was quoted saying, “I feel my whole body burning.”

States are going to extreme measures to obtain lethal injection drugs. Missouri paid $11,000 in cash to obtain pentobarbital from a compounding pharmacy so it wouldn’t leave a paper trail. In Texas, a compounding pharmacy demanded that pentobarbital purchased by the state be returned after its identity was leaked. And in Oklahoma, the state reportedly spent $40,000 in petty cash in 2012 from an unknown pentobarbital supplier. The pharmacy’s identity has been kept anonymous under the state law.

Oklahoma’s execution delays won’t be the last. Without a significant change in the way states carry out executions—possibly including a reversion back to older execution methods—corrections departments will continue running into obstacles as lawsuits pile up and pharmacies continue denying states the drugs they need.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com