Nobody expected the United States to emerge out of the group stage in this month’s World Cup. Yet by compiling a 1-1-1 record against Ghana, Portugal and Germany, they squeaked by thanks to FIFA’s score differential rule. Hundreds of thousands of fans of the U.S. team celebrated long and hard Thursday night. Around the globe, hundreds of millions of soccer fans have been doing the same.

Brazil is throwing a party that, in the end, will cost it somewhere between $15 billion and $20 billion, according to a report in Sports Business Journal. FIFA keeps the revenue from TV rights, tickets, corporate sponsorships and marketing. Brazil gets to keep, in my estimate, around $500 million from tourist spending. That’s not a very favorable equation.

South Africa spent around $6 billion for the 2010 World Cup. Germany (2006), France (1998) and the United States (1994), with developed infrastructure and modern stadiums, spent less than a billion each. When they co-hosted in 2002 and built new facilities, South Korea spent $2.5 billion and Japan $5 billion.

Here’s part of Brazil’s problem: FIFA requires that each host country have eight modern stadiums with at least 40,000 capacity, one of which seats 60,000 for the opening match and another with 80,000 capacity for the final contest. That threshold alone would have been difficult enough to meet, but Brazil decided to do one better: in the hopes of exposing 12 of its cities to the world, Brazil committed to having 12 venues, each with a minimum capacity of 40,000.

In 2009, the Brazilian Football Confederation initially estimated the 12 stadiums being refitted or built for the World Cup would cost about $1.1 billion. The total stadium budget eventually rose to more than $4.7 billion. Nine of the stadiums were new, and of these seven were built on the site of existing stadiums that were demolished. Four stadiums were built in cities with no football team in the first division of Brazil’s soccer leagues. In Manaus, there is a second division team with an average attendance of around 1,500 per game. Manaus now has a new stadium with a capacity of 42,374, at a cost of $325 million. It will be used for a grand total of four games during the World Cup.

The Mane Garrincha National Stadium cost a reported $900 million to build and has a capacity of more than 70,000. Fortaleza, Recife and Salvador all have football teams in the first division, but the average attendance per game is around 15,000, with an average ticket price of $10. Recife already had three large, multi-purpose stadiums. The populations in these cities do not come close to having the purchasing power to pay ticket prices high enough to maintain those stadiums, let alone to service the construction debt.

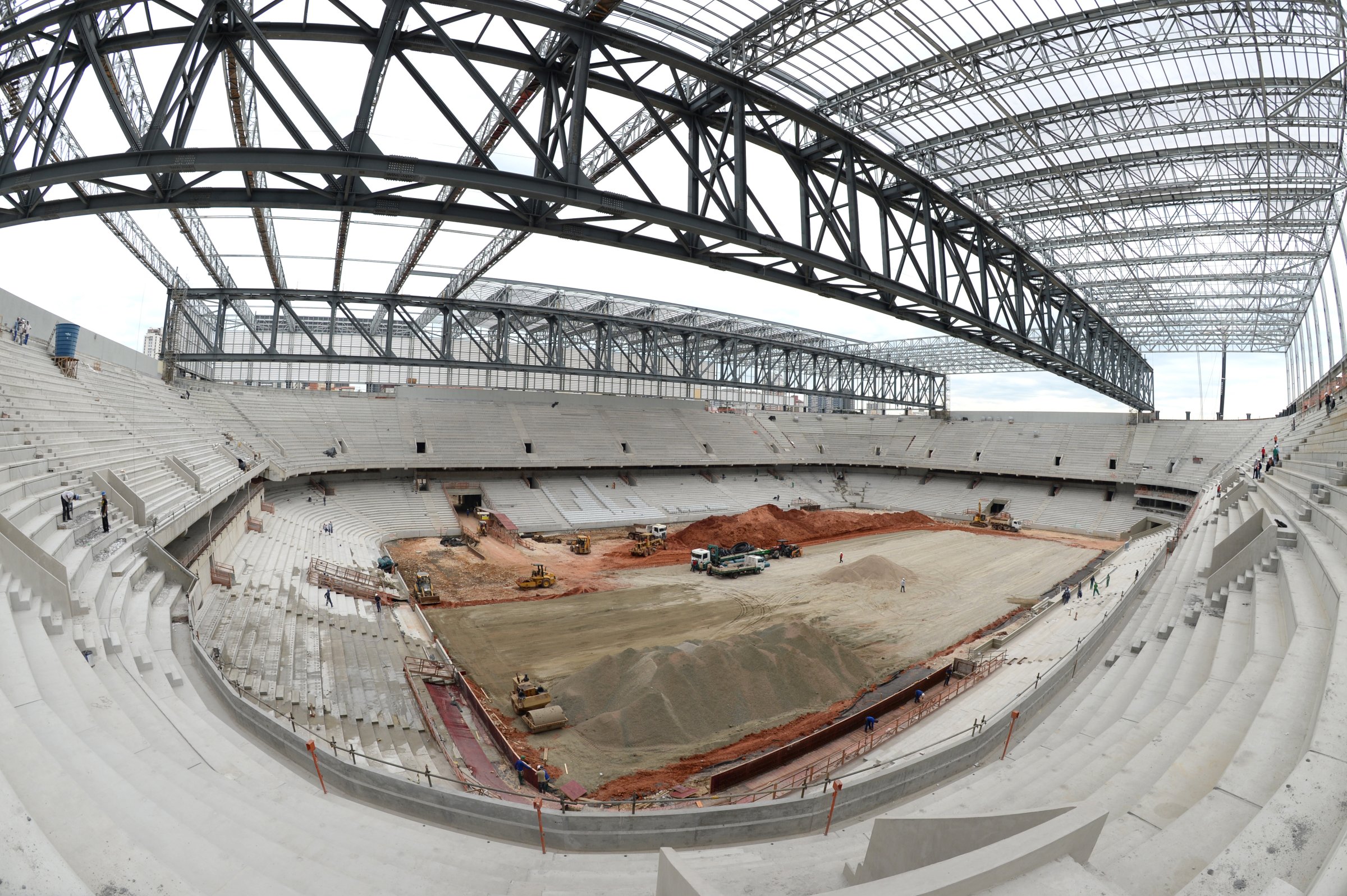

In São Paulo, the venerable Morumbi Stadium was excluded from the World Cup because it didn’t meet FIFA’s standards. The local organizing committee for the World Cup decided to build a new stadium rather than refurbish Morumbi. After its overview visit to Brazil in May 2011, FIFA required enhancements to the new facility’s design. Those upgrades carried an estimated price tag of $650 million, a 30% increase in the total cost. The construction was disrupted in early 2014 when a crane collapse destroyed a good section of the stadium; a work stoppage followed.

At the famous Maracanã Stadium in Rio, which was originally built for the 1950 World Cup, there was a $200 million renovation for the Pan American Games in 2007. That renovation was not sufficient in FIFA’s judgment, so subsequent to the Pan American Games, Maracanã Stadium was partly demolished and then rebuilt for more than $500 million. Part of the rebuild required the demolition of the Indigenous Cultural Center (the first indigenous museum in Latin America), a school and a gymnasium to allow for a parking garage. A nearby water park was also leveled.

The land was slated to become a parking lot, but, as the World Cup matches began on June 12, 2014, there was no lot there. Seven-hundred families had been displaced. The first 100 were removed at gunpoint and resettled two hours away in a western suburb of Rio. The remaining families protested and sued, and eventually received better treatment.

The non-sport infrastructure investments for the Cup principally involve the construction of rapid bus lanes to transport officials, athletes and fans from the airport and hotels to the stadiums and new airport runways or terminals. Security costs likely will rise above $1 billion.

Apart from an estimated 250,000 poor Brazilians who have been relocated from their homes, the country suffers from highly deficient public health and education systems and woefully inadequate public transportation. It is little wonder that massive demonstrations and strikes accompanied the build-up to the World Cup.

It will all be over in a few weeks and the Brazilian government will have a massive bill to pay – both to its bondholders and to its people. The party’s hangover is coming.

Andrew Zimbalist is the Robert A. Woods Professor of Economics at Smith College. His latest book is The Sabermetric Revolution: Assessing the Growth of Analytics in Baseball.

See the 2014 World Cup Stadiums in Brazil

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com