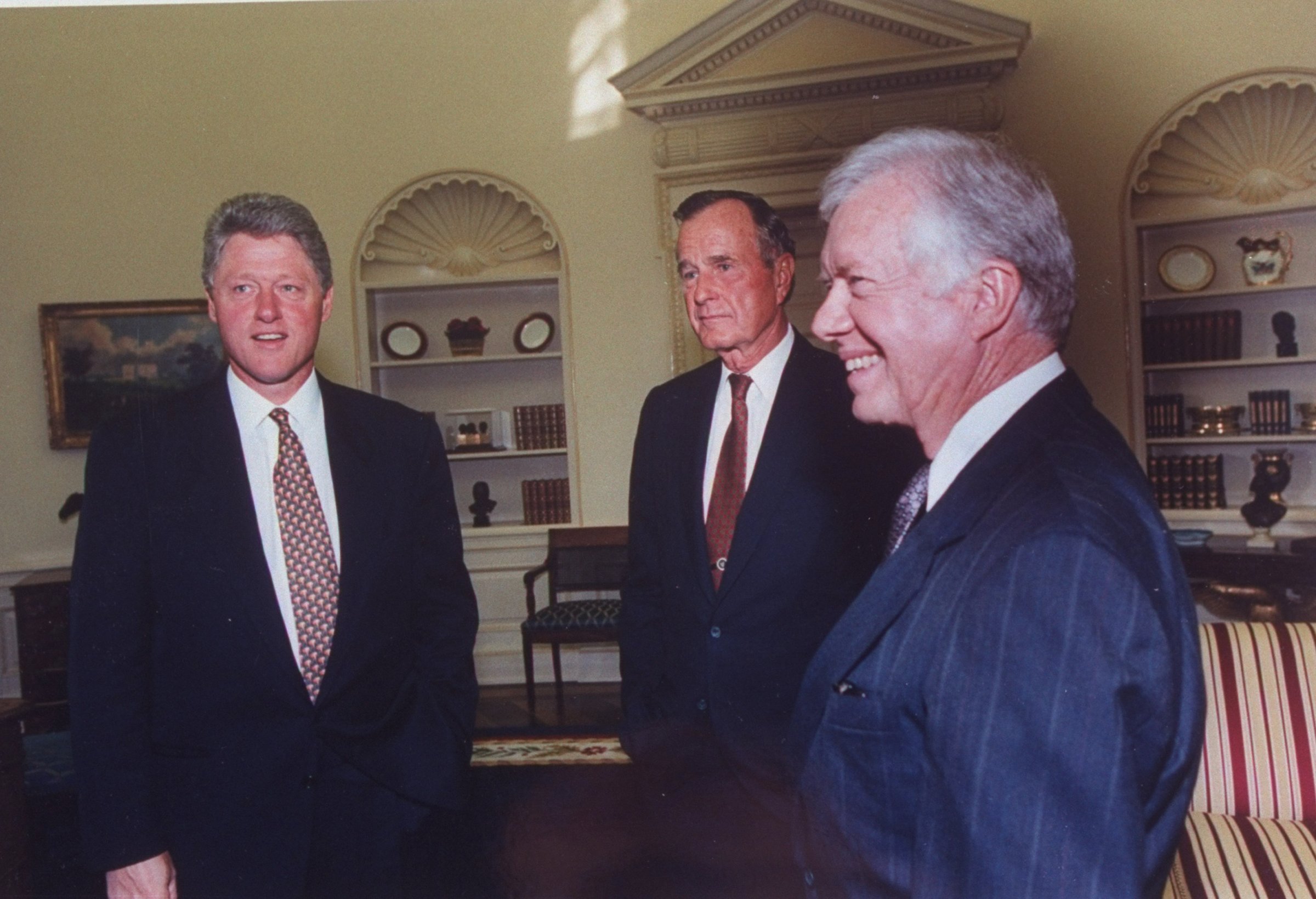

Bill Clinton got the photo op handshake but, in the end, failed. So did Nobel Peace Prize winner Jimmy Carter. John Kerry joins a long list of men – Yasser Arafat, Yitzhak Rabin, Ehud Barak, George Mitchell – who have unsuccessfully tried to forge peace in the Middle East.

But all of these failed leaders have something in common – and it may be a reason why the process continues to stagnate. They are all men.

“We’ve studied freedom struggles over the last century, and none has succeeded without women’s leadership,” said Ronit Avni the Founder and Executive Director of Just Vision, at a recent roundtable at New America. “We saw their leadership as both a strategic necessity, and something intrinsically valuable.”

Embracing women is much more than a gender parity strategy: It’s key to building a successful movement. “Pluralistic movements are more likely to be nonviolent,” said Avni. “Violent actors have to operate in very hierarchical structures, and have to operate with physical strength and in secret. Pluralistic, unarmed movements need to operate with everyone. Think about the Civil Rights movement and the feminist movement.”

Avni didn’t set out to agitate for gender equality in the Middle East. Rather, her mission is to contribute to a future where Palestinians and Israelis can enjoy equality, human security, freedom and possibly peace. Including more women at the negotiating table doesn’t guarantee a resolution to the occupation or to the ongoing conflict – especially if the women at the table are reinforcing frames of militarism, she said. But excluding women will, invariably, “lead to a future that is very dark for Palestinians and Israelis. Inclusion doesn’t mean we will get there without challenging the imbalances of power.”

That power asymmetry means that replacing Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas with women from their respective governments wouldn’t fundamentally change the process. Take the most recent example of that imperfect strategy: Tzipi Livni was the lead Israeli negotiator, representing Netanyahu, during Sec. Kerry’s latest peace process attempt. Hanan Ashrawi is on the Executive Committee of the PLO, the first woman to hold that position.

But in this context, their presence doesn’t make a huge difference, “because women aren’t there as a constituency,” explained Leila Hilal, a senior fellow in New America’s International Security Program, and a former legal adviser to Palestinian negotiators. “Women aren’t present [during these discussions] as a representative group, nor are the issues that women would likely prioritize on the agenda, such as social needs and equality.”

Indeed, having women who are merely mouthpieces for their governments could perpetuate existing inequalities and dead-end ideas. What will change the process is a discussion of the situation with a pluralistic lens. “Having women involved [can] force a conversation about equality and pluralism,” Avni said.

Women leaders were key to defusing the conflicts in Guatemala, Northern Ireland and Darfur. During those talks, they elevated topics of inclusion, equality and rights – how to balance power between civilians and the government, and how to address the needs of victims.

And though women have been all but absent in the most recent negotiations – for instance, there were no female negotiators or technical advisers present during the infamous Camp David talks under Clinton – they were among the most active players after the first intifada, and part of the delegations to the first multilateral peace talks in 1991 between the PLO and Israel.

So what happened to push the women out?

“This process was ultimately usurped by the Oslo Accords in 1993, which ultimately placed negotiating power in the Palestinian Authority rather than the more representative PLO,” explained Hilal. “The Accords ushered in an era of bi-lateral, exclusive and for the most part secretive peace ‘processing’ that has left much of the Palestinian and [arguably] Israeli populations alienated from the official track.”

Some contend that the exclusion of women during the Oslo process made a tangible difference in the outcome. Had male peace negotiators asked Israeli and Palestinian women about the Oslo Accords strategy, “they would have suggested slight changes to the way the lines were drawn that could have greatly improved access to land and water and better maintained the integrity of communities,” writes Carla Koppell, USAID’s chief strategy officer, and Rebecca Miller, a technical advisor at Mercy Corps (both formerly of the Institute of Inclusive Security).

That may be partly because women have different values – and perspectives – than men. “Women tend to raise social issues that men overlook,” said Hilal. “They talk about education, water, healthcare – those everyday topics that aren’t considered high politics.” Here comes that now hackneyed, but important, caveat: women in neither society are a homogenous group. But a recent survey suggests that in Israel, women value peace more than men.

“Women in conflict have different lived experiences,” explained Kristin Williams, a senior writer and program officer at the Institute for Inclusive Security. They understand better certain discriminatory inheritance laws and would raise right of return issues. Yet, those subjects are left out because peace negotiations tend to be exclusive, involving military personnel or high-level political actors. An elite old boys club banging fists on the table behind closed doors.

Beyond leaving out women and gender issues, that leadership opacity has inculcated distrust among the public, Williams said. How do we make the process more effective? Expand it.

But there’s another obstacle: finding the women to plug into the conversation, to expand the urban elite circle. For example, it’s challenging to cultivate female leadership in the Palestinian Territories, where rural communities tend to be more conservative than urban ones and where men on the periphery discourage women from speaking out.

“It’s really hard for women in my community to do something because no one is paying attention to them,” said Rula Salameh, a Palestinian education and outreach coordinator for Just Vision. “No one sees them as a key element in the Israeli Palestinian conflict – no one is seeing them as a key player in anything.”

So how do we get to a more inclusive process – one that may have a better chance at success? For Salameh, the answer is focusing local and international efforts on boosting female grassroots leaders working in isolated villages and refugee camps – to widen the network of leadership beyond Ramallah, Jerusalem and Bethlehem. Laws to involve more women have proved mostly ineffective on both sides: A gender quota in the Palestinian Authority government hasn’t translated into gender parity in the diplomatic process or in the distribution of power. An amendment to Israeli law that mandates women’s inclusion in negotiating committees hasn’t been fully implemented.

Another answer: don’t forget about the men. They can be powerful allies. “The most effective approach is meeting with men [in each community],” said Salameh. Building trust with the local leaders will either open doors for women, she said, or at least mitigate the dissent and pressure they face when they decide to lead.

Elizabeth Weingarten is the associate editor at New America and the associate director of its Global Gender Parity Initiative. This piece originally appeared at The Weekly Wonk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com