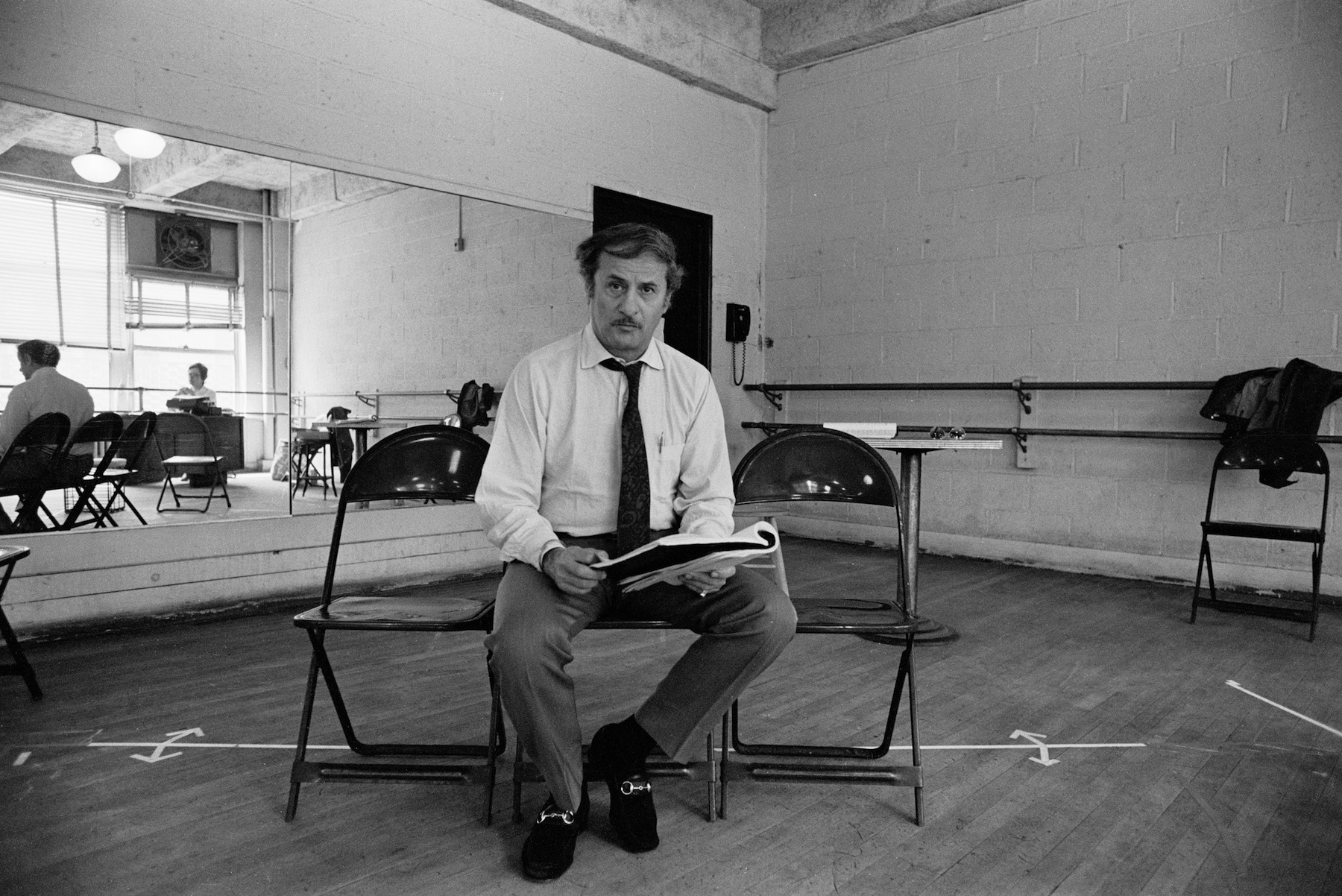

Tonight, June 27, in honor of his long career in film and theater, Eli Wallach will receive Broadway’s equivalent of a flag at half mast. At a quarter to eight, for one minute, the marquee lights of New York’s Broadway theaters will dim to acknowledge his death earlier in the week. As noted by the Broadway League, the theater-industry organization that makes these decisions, Wallach was in more than two dozen Broadway shows, beginning with a 1940s production of Skydrift and including such notable titles as Major Barbara and Rhinoceros.

Though the dimming of the lights sounds like one of those things that must be as old as theater itself — or at least as old as light bulbs — it’s actually a tradition that began during Wallach’s lifetime.

Charlotte St. Martin, the executive director of the Broadway League, told Playbill in 2010 that nobody knows how the tradition got started, but it’s pretty easy to guess. After all, the first person to be honored in that way was in a show when she died, so the people running the lights were her current co-workers, not her distant admirers. The first person to receive the honor, according to the New York Post, was Gertrude Lawrence, an actress who was killed by viral hepatitis while starring in The King and I. The New York Times reported that she went into the hospital right after a matinee in August; by the first week of September, she had fallen into a coma. She died on a Saturday and the Tuesday performance of The King and I was cancelled in her honor; as the Times described it, “house lights in all Broadway legitimate theaters giving performances tonight will be dimmed for one minute at 8:30 P.M.” In addition, London theaters would dim their house lights — that’s inside the theater, not outside — at 7:30, which was their curtain time.

As Playbill confirms, the tradition, which started in the early 1950s, got off to a slow start, with only three such ceremonies in the first 25 years. The second on their list was the one to take it from inside the house to outside on the marquee. When Oscar Hammerstein II died in 1960, Broadway went all out: the Times reported that “miles of neon lights and thousands of bulbs from Forty-second to Fifty-third Street and in the side streets between Eighth Avenue and the Avenue of the Americas were turned off”; street lamps were dark too and thousands of people gathered to hear two musicians play taps. But, though that ceremony was elaborate, it’s not quite so clear-cut as to say it was the second-ever dimming, period. It was the first time since World War II that all of the outside Broadway lights were dimmed — in 1942, the Army tested whether the city could go dark in the case of air raid — but it was neither the first time that inside lights were dimmed (that was Lawrence) or that just a few marquees were dimmed.

These days, dimming happens much more frequently. This year, so far, the Broadway League has announced dimming of the lights in honor of Ruby Dee, Nicholas Martin, Mitch Leigh and Philip Seymour Hoffman.

But quantity doesn’t necessarily mean quality. As the tributes get more frequent, they seem to have gotten less precise; the light-dimmers have recently been criticized for failing to mark the minute named by the Broadway League. When James Gandolfini received the honor in 2013, the New York Post noted that not every theater participated or participated at the right time. Without that coordination, the gesture doesn’t have much of a visual effect. You can see for yourself, around 0:33 in the below video:

Still, the difficulty of coordinating such a tribute is nothing new. When Eli Wallach was a teenager growing up in New York City, for example, long before Broadway stars could hope to be honored with dim marquees, he might have even seen an example first hand: in 1931, to mark the memory of Thomas Edison, the entire nation participated in a ritual dimming of the lights, to celebrate his contribution to electricity. Broadway was joined by the Statue of Liberty and the White House in turning off the lights during a special radio broadcast at 9:59 P.M. Eastern Standard Time. But, despite the grand gesture, not everything went off without a hitch. “In New York,” the New York Times wrote on Oct. 22, 1931, “the tribute, though spontaneous, was intermittent despite the city’s efforts to synchronize the tribute.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com