My favorite sentence in Hillary Clinton’s very diplomatic memoir of her time as Secretary of State is: “So I sat through hours of presentations and discussions, asking questions and raising concerns.” The hours of discussions took place at a U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, a regular summit Clinton has labored mightily to create between the two most powerful countries in the world. She has spent dozens of hours with Chinese State Councilor Dai Bingguo, establishing a personal relationship because of a fundamental belief that regular meetings–architecture, the diplomats call it–can mitigate damage when crises occur. This is, in fact, her core diplomatic creed, the predicate for an orderly, “rules-based” world. You might say, Well, that seems obvious. Yes, it is. But if you want to know what Hillary Clinton is all about, this is it. Except when it isn’t.

You might also have noticed a certain tension, and perhaps irony, in the sentence. It sounds as if she might have wanted to be doing something else, and that is true: she was in the midst of a crisis. Just before the summit meeting, a blind Chinese dissident named Chen Guangcheng had evaded house arrest and phoned the U.S. embassy asking for refuge. If she granted it, she might blow up the strategic dialogue. “It appeared that I had to decide between protecting one man,” she writes, “and protecting our relationship with China.” She decided, crisply, that the U.S. could not turn away Chen. “In the end it wasn’t a close call,” she writes. “America’s values are the greatest source of strength and security.” So much for architecture. So much for Clinton’s inflexible image. She can be daring too.

There follows about 20 exciting pages–if you’re into the nitty-gritty of diplomacy–of two-track diplomatic haggling, as Clinton and her aides try to save the talks and figure out what to do with the dissident. Chen agrees to a plan to go to law school in China, then changes his mind. He gives interviews to the world media from his hospital bed, angering the Chinese. But they go forward with the summit, and Clinton has to decide between negotiating with the dissident and sitting through the reassuringly boring strategic dialogue. She chooses the “hours of presentations and discussions,” leaving the negotiations to her staff, who arrange a visa for Chen so he can study law in the U.S. The rules-based relationship with China is reinforced. Eventually Clinton’s patience pays dividends: the Chinese cooperate on issues like the Iran economic sanctions and North Korea.

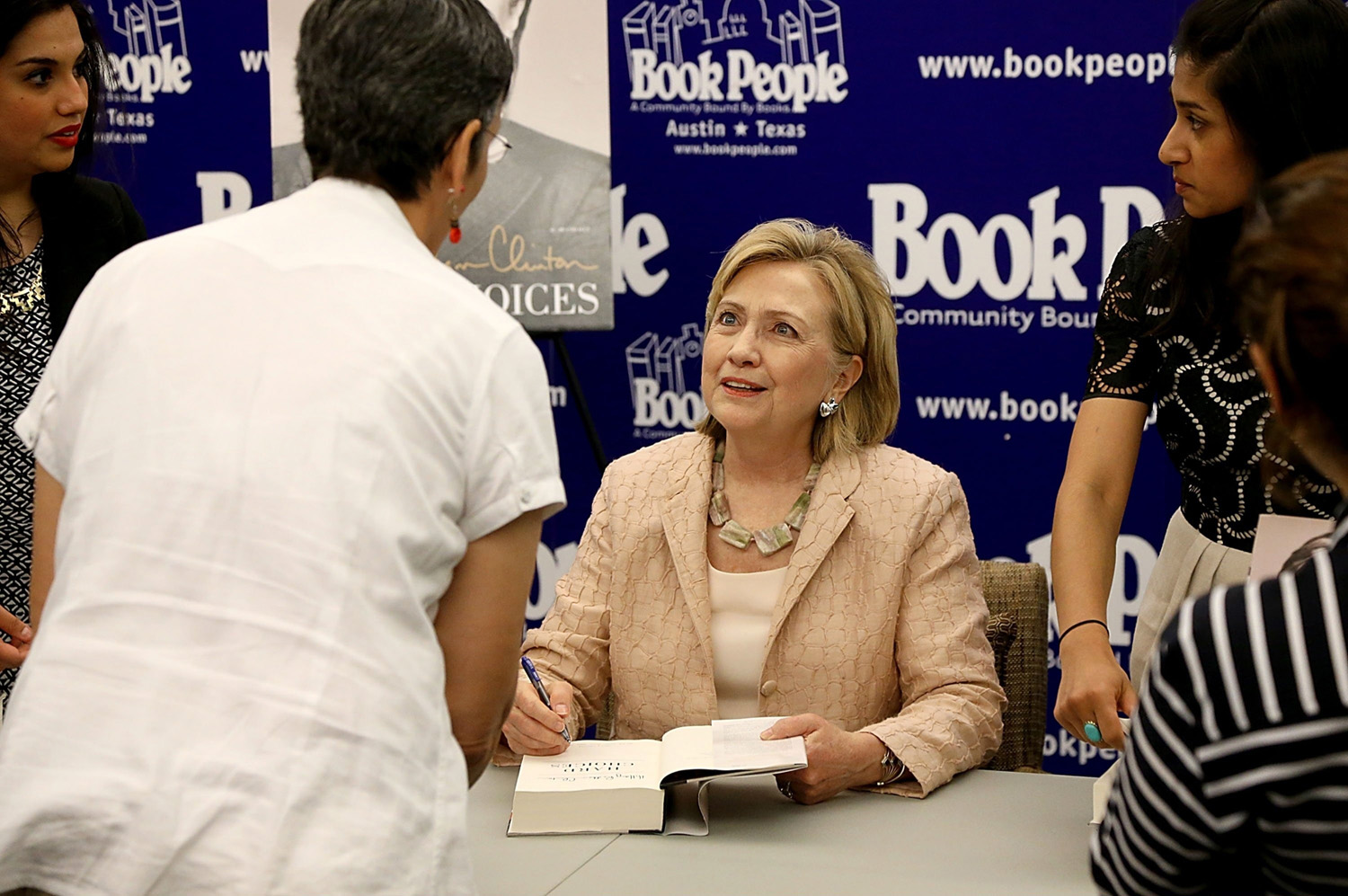

So there is value, and even some entertainment, in Hard Choices, although you’d never know it from the reception the book has received. Clinton is partly to blame for that, as she allowed the memoir to be rolled out as part of a big presidential guessing game, with an elaborate embargo scheme that made it seem as if there were newsy revelations within. There aren’t. Read as a presidential manifesto, it is a tease. Read as a personal memoir, it is a desert. The journalists scouring the book for gossip found that she digs her fingernails into the palms of her hands to fight off jet lag during diplomatic meetings, and little else. Hard Choices has been roundly dismissed as boring. And yes, there are broad narcoleptic swatches of wallpaper-writing as every last country and issue–Here’s to you, Northern Ireland! Here’s to you, climate change!–are given their thousand-word shout-outs. The writing, which can be just fine when the ghostwriters are attempting narrative, lapses all too often into deadly speechwriterese: “Will Africa’s future be decided by guns and graft or growth and good governance?” Yikes. Memo to Democratic ghostwriters: It’s time to shed the alliterative Ted Sorensenian “Ask not” switchbacks and pass the torch to a new generation of readership.

But there is a lesson here too. It has to do with patience and perseverance and the close work of getting the details right. “It is easy to get lost in the semantics,” she writes, “but words constitute much of a diplomat’s work.” And some of the best passages in Hard Choices concern word wrangling, especially with the Russians. The work isn’t very dramatic or sexy; it is the governmental equivalent of solving a crossword puzzle. It is essential to successful statecraft, however–a point that George W. Bush didn’t seem to understand until his second term in office.

Amid the daily concussion of press coverage during crises, Clinton battles for the free world, comma by comma. At times, as in the negotiations over whether to use military force in Libya, she loses perspective. She begins highly skeptical about the efficacy of a strike against the Gaddafi regime, which is threatening to massacre civilians in Benghazi. She asks the right questions: “Who were these rebels we were aiding and were they prepared to lead Libya if Gaddafi fell?” She sides with Defense Secretary Robert Gates–always a safe bet–against the White House aides who favor intervention. Then she changes her mind, lured by the siren song of multilateralism. The Arab League wants U.S. military action in Libya–that’s a breakthrough! The Europeans, especially the French, are ready to roll. She never says explicitly that she changes her mind–Gates says she does in his memoir–but it seems that Clinton has fallen for the promise of closer cooperation with the normally intransigent Arabs and the unusual willingness of the Europeans to take up arms. Of course, within days, the Arab League criticizes the U.S.-organized bombing campaign, and the Europeans don’t have the military wherewithal for a sustained fight. She also neglects discussing the consequences of her decision: the anarchy that is now Libya, the rule by militias that eventually results in the murder of U.S. Ambassador Chris Stevens and three others in Benghazi. (Her chapter on Benghazi is comprehensive and logical, though few of the Fox hounds who see the issue as a matter of theology, not facts, will buy it.)

Clinton can be selectively disingenuous. Her chapter on Middle East negotiations dwells on the overreaction in the region and in the press when on Halloween night in 2009 in Jerusalem, she calls “unprecedented” Israel’s offer of a 10-month freeze on West Bank settlement except for Jerusalem. And yes, it may well have been unprecedented in technical terms, but other words more accurately describe the Israeli move: partial, grudging, unacceptable. The rest of the world considers Israel’s settlement building in contested areas an illegal provocation. But there is a more troubling, and personal, subtext here. Clinton doesn’t mention it, but she had established–and perhaps overstated–the Obama Administration’s hard line against the illegal settlements five months earlier, when she’d said, “[The President] wants to see a stop to settlements–not some settlements, not outposts, not ‘natural growth’ exceptions … That is our position.” Her acceptance of Israel’s partial freeze was a retreat from that hard line, a public retreat that dismayed the White House. “Why does she do that?” a senior Administration official asked me at the time, referring to her initial harder-than-necessary position and later “unprecedented” retreat.

Because she is human. She does not always come equipped with a natural politician’s body armor or habitual flight to the anodyne. She has an advocate’s fervor–especially when it involves women and children. She’s got a temper. She displays it in Africa when asked about her husband’s position on a complicated World Bank issue, a question that seems to denigrate her importance. “Wait, you want me to tell you what my husband thinks? … My husband is not Secretary of State.” She knows this is wrong and apologizes quickly to the young man who asked the question. But I would guess that one of the reasons Clinton seems so buttoned-up in public is a fear that she’ll unleash an arrant display of imperfection. Unfortunately, this deprives the public of her wicked sense of humor and commonsense candor–which is on occasional display, but on a very short leash, in Hard Choices. She is happy to admit her glaring, well-known mistakes, like her support for the war in Iraq. But she is wary of copping to lesser, if more telling, diplomatic misjudgments–on Libya or her support for the second Afghanistan surge. Again, Gates’ book is more candid: Clinton supported an even larger number of surge troops than he did. She does not mention that in Hard Choices.

She admits to disagreements with President Obama–on whether to arm the Syrian rebels, for example–but the disagreements are ridiculously civil and vague, especially when compared with the blue rages that Gates describes himself throwing in his memoir. The only memorable verbal scuffles she describes are with foreigners. And these are either resolved over time or not, equably.

That the Hard Choices book-tour extravaganza has been a bit of a bomb has more to do with the public atmosphere than it does with the book, which is a cut above the sort of thing you’d expect from a Secretary of State–although several cuts below Gates’ riveting candor. Its most important lessons–about patience, management, the importance of details, the slow building of personal relationships–are precisely the skills that we seem to ignore in the public arena these days. We are impatient with anything beyond simple declarative sentences, the more hortatory the better: “Assad must go.” But diplomacy and good government exist in a mind-numbing haze of clauses and nuance. Clinton makes the case that she has mastered the placement of commas and that she has the patience to negotiate with opponents, foreign and domestic. That is the purpose of the book: to demonstrate that she would bring these quiet attributes to the presidency. In this moment of blare and paralysis, it is a subtly clever argument to make. Too subtle, perhaps.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com