Jeff Koons’ studio, a building that occupies a quarter block on Manhattan’s West Side, is a bit like a mad scientist’s laboratory. In one white-walled room after another, Koons and his staff of about 130 work on a dozen or more projects simultaneously. Some comb the Internet, which is where Koons tends to find the images he knits together via software into paintings his assistants execute under his supervision. Statues in progress–a classical figure in stainless steel, a pink ballerina–face off in a room where Koons and his assistants fetishize every surface. To produce the latest generation of his mighty playthings, those scaled-up riffs on balloon animals, heaps of Play-Doh and the Incredible Hulk, Koons uses 3-D digital scanning and computer-controlled manufacturing. His studio has even developed its own steel alloy. To him it’s all about his favorite topic: his earnest relationship to his audience. “You don’t care about the object. It’s just an object,” he says. “But spending time on the details is a metaphor for the care and attention you give the viewer.”

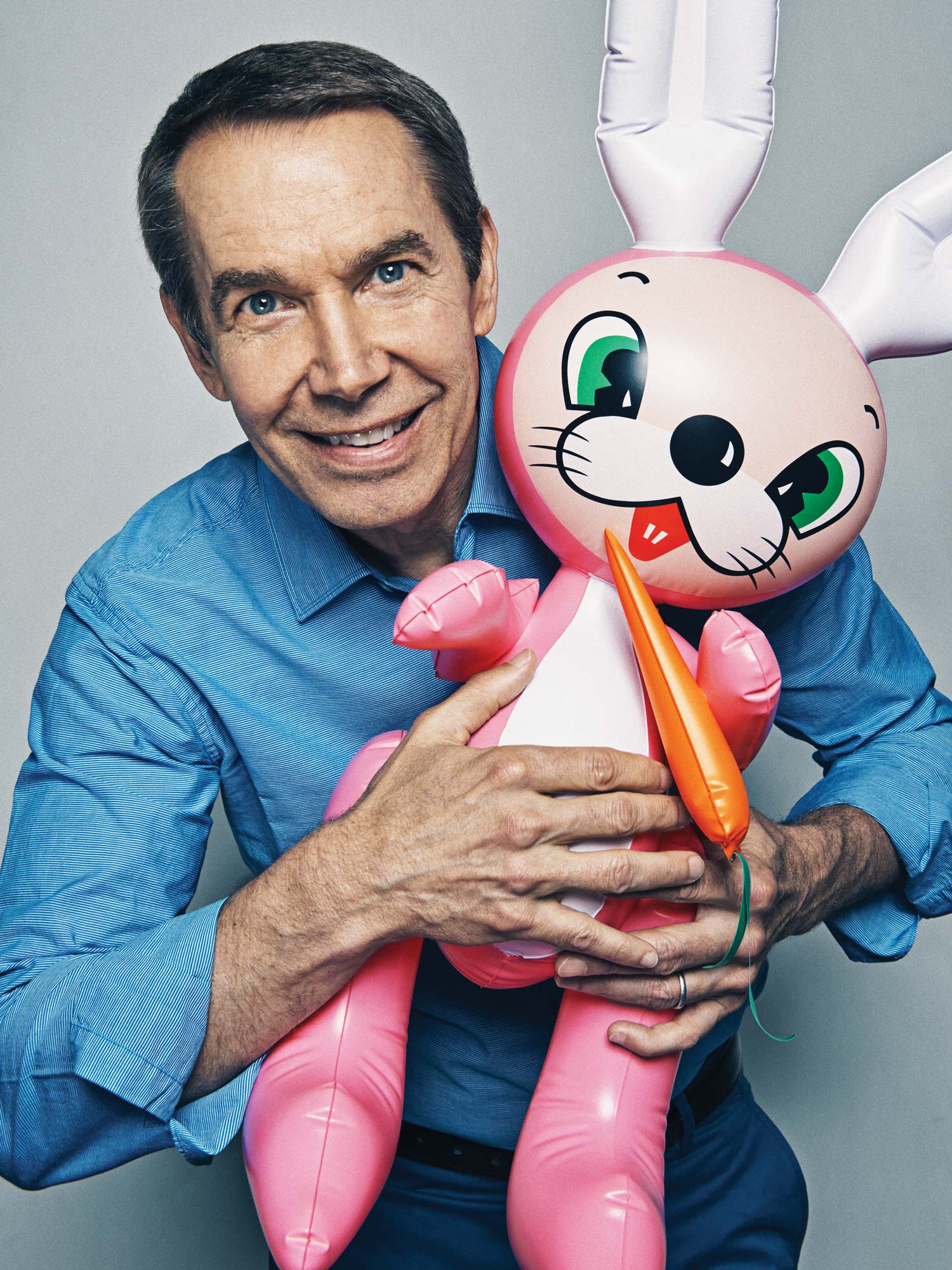

With his perennial expression of childlike awe, can Koons really be 59 this year? No one except Pee-wee Herman and Michael Jackson has spent more of his career luxuriating in the world of childhood while also inhabiting a parallel universe of adult sexuality. From the time he first started exhibiting in 1980, when he was 25, Koons was art’s eternal man-boy, an impression that his subsequent lifetime of work, all those balloon dogs and pool toys, has done nothing to discourage. So are we ready for him to become one of the grand old men of American art? It’s like hearing that Howdy Doody just got his AARP card.

But it must be true, because Koons is finally being accorded that key signifier of art-world ascendancy–a full-career survey show in New York City. It comes surprisingly late in his career, but as compensation it’s so large that the Whitney Museum of American Art is emptying most of its exhibition floors to contain it. “Jeff Koons: A Retrospective” continues there through Oct. 19, then moves to the Pompidou Center in Paris and the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. “I’m really excited about the show,” he says. “I hope my work will reach a new generation of artists, people who feel they’re familiar with it but haven’t actually experienced it. I’ve had very few exhibitions in the United States.”

That’s not quite right. Koons has had any number of gallery shows in the U.S. but few solo museum exhibitions. That’s partly a reflection of the difficulty of gathering his immense works together. But it also might stem from an ambivalence in parts of the museum world about coronating the guy whose work revolves around Popeye and plastic kittens yet can cost more than a Hamptons estate. Last November, Koons achieved the record auction price for a living artist when someone paid $58.4 million at Christie’s in Manhattan for Balloon Dog (Orange), a 10-ft.-high (3 m) stainless-steel sculpture that manages to be sweet, mesmerizing and slightly intimidating, a monumental equestrian statue for an unheroic age. But Koons hates it when people focus on his prices. “It’s not about the money,” he says. “As a young artist I wanted to be engaged in the excitement of making art and sharing ideas. And that hasn’t changed–that’s what the art world represents to me.”

Endearing but enigmatic dogs turn up often in Koons’ work. His most famous is Puppy, from 1992, a 40-ft.-tall (12 m) terrier made from thousands of live flowering plants. A work so purely gratifying it all but salivates, it could have been made only by Koons, who in conversation is so anxious to ingratiate that you half expect him to wag his tail. His odd but not unappealing self-presentation, a lifelong work of performance art in itself, is a compound of militant cheer, apparently guileless manner and loopy-oracular musings, with frequent but not always lucid references to “the eternal” and Plato’s cave. Yet for all his canine longing to be loved, to reach the largest possible audience, Koons’ work leaves a lot of people unmoved: too puerile, too cheerfully aimed at mass taste and too much in tune with the rise of juvenile formats in 21st century culture–comic books, fantasy fiction, Japanese anime. For a lot of people (I’m one) the high sugar content of his art means it works only when it carries adult contradictions within it, a trace element of irony or a glimpse of the angel of death. And then there’s the problem of Koons as symbol and leading indicator of the runaway commercialization of art. By now he’s won over every billionaire collector. But he knows that the response to the Whitney retrospective will tell how much he’s won over the skeptical quarters of opinion–to say nothing of whether the skeptics even matter anymore.

Birth of a Salesman

Koons grew up in York, PA., an old industrial city where his father owned a furniture store and did interior decorating. In the catalog to this retrospective, Scott Rothkopf, the Whitney curator who organized the show, suggests that the future artist may have learned about the power of objects from the model living rooms in his father’s store. Koons concurs. “I learned aesthetics through my dad,” he says. “How different textures, images and combinations of things could affect the way you feel.” By his teens Koons was a salesman himself, happily peddling wares like ribbons and gift wrap door to door. After passing through art school in Baltimore and Chicago, he headed to New York in 1977 and found himself selling again, this time memberships at the Museum of Modern Art. Decked out in big bow ties and floral vests, he outperformed the rest of the sales staff by large margins.

At MOMA, Koons became more aware of Marcel Duchamp and his readymades, objects–a urinal, a bottle rack, a shovel–that Duchamp designated as art simply because he chose them. In school Koons had been interested in Surrealism, and his student work drew on his fantasies and dreams, but by his early 20s he wanted to go beyond his interior life. “You want to get outside yourself and affect how others feel,” he says. “The readymade for me was a way to move from a subjective to an objective realm.”

He started by buying inflatable flowers and bunnies, which he mounted on mirrors. By 1980 he had upgraded to bigger, shinier objects, encasing pristine vacuums and floor polishers in clear acrylic boxes lit with fluorescent tubes. This was the household appliance as revered object, spotlighted to isolate its newness, a key to its mystique as merchandise.

Top-of-the-line carpet cleaners cost a lot more than vinyl bunnies. To finance his new work, Koons took a job selling mutual funds. Even so, he went broke and moved in with his parents, who had retired to Florida. A few months later he relaunched himself in New York, this time selling commodities while he assembled his first solo gallery exhibition, a 1985 show called “Equilibrium” built around notions of floating, sinking and basketball. Its signature works were the Total Equilibrium Tanks, blue-glass aquariums that held one or more basketballs submerged in the precise combination of distilled water and saltwater that kept them suspended in the center of the tank. Though they borrowed ideas from Pop art and minimalism, these were some of the oddest objects ever produced under the rubric of sculpture–beautiful, strange and vaguely human. As Koons likes to point out, “each basketball is like an embryo in the womb.”

In his next phase, Koons began casting sculpture out of stainless steel, “the luxury material of the proletariat” as he once called it. Rabbit was a silver balloon toy painstakingly reproduced in mirrorlike steel, with curves that quoted the silhouettes of a Brancusi sculpture. Elevating kitsch objects into museum-quality work would become his signature practice and the basis for his next show, “Banality,” in 1988, which transformed Koons into a true phenomenon as well as the whipping boy for the showmanship of the ’80s art world. He collaborated with craft studios in Italy and Germany, with wood carvers and ceramic and porcelain artists, to produce 20 giant versions of tacky knickknacks: a half-naked woman being hugged by the Pink Panther, a Cabbage Patch Kid in a bib and a larger-than-life gilt porcelain of Michael Jackson cradling his chimp Bubbles–all designed by Koons but in the generic idioms of gift-shop novelties.

Pop artists like Claes Oldenburg had made scaled-up specimens of mass culture before, but usually with tongue in cheek, holding the mass-produced world at a remove. Not Koons. He was unapologetically in love with it, and he still insists that his lowbrow imagery helps viewers shed embarrassment at finding pleasure in trashy stuff. “By removing anxiety, you can really have everything in play,” he says. “If you have acceptance for everything, you’re in a position of maximum freedom.” Or as Andy Warhol once said, Pop art is about “liking things.”

Whether most people really feel shame about the pleasure they take from the flotsam of pop culture is an open question. But to enjoy Koons you don’t have to believe that hierarchies of taste are obstacles to human happiness, any more than you have to accept the divine right of kings before you can enjoy Van Dyck’s lush portraits of Charles I. All the same, Koons knew that urging people to shed what you might call judgment and discrimination would get him in trouble. He decided to strike a pre-emptive blow by placing ads in four art magazines brazenly featuring himself as an evangelist of kitsch and a would-be leader of the art world. In one he sidled up to an actual pig while cradling a little piglet in one arm. “I thought I would call myself a pig,” he says, “before anyone else could.”

“Banality” was a huge financial success and got no worse than mixed-positive critical reaction. It was his next effort that turned out to be a huge stumble. Koons came across a photograph of Ilona Staller, a Hungarian-born porn actress known as La Cicciolina (“the little dumpling”), who was also–why not?–a sitting member of the Italian Parliament. Intrigued, he recruited her to appear with him in an art-project billboard for an imagined film, Made in Heaven. The film never got made, but Koons and Staller plunged into an improbable marriage that he commemorated in a series of XXX-rated sculptures and oil paintings in which they engaged in sex every which way. Granted, there were cartoonish topless babes in the “Banality” series, but explicit sex–featuring himself, no less–wasn’t what people were prepared to accept from the guy who made giant teddy bears. Though the work resonated with Koons’ beliefs about shedding guilt–even now he says “it was about acceptance and accepting one’s self”–it made a lot of people shudder. Also, it was hard to sell.

There was worse to come. In 1992 the marriage of Koons and Staller, which would soon disintegrate, produced a son, Ludwig. Though American courts awarded custody to Koons, Staller took the child to Italy, ensnaring Koons in years of largely futile court battles to get him back. But Koons’ anguish over their separation led him into one of the most fruitful episodes of his career, the decade-long Celebration series, sculpture and paintings built around happy things: a slice of cake, a pile of Play-Doh, the famous balloon dogs. Koons hoped his son would someday see them as evidence that his father never stopped thinking about him.

The expense and difficulty of fabricating those works to Koons’ notoriously demanding standards also brought him to the edge of bankruptcy, but the struggle, now long behind him, was worth it. Though the paintings are rarely as interesting as the James Rosenquist Pop art they owe so much to, and though his efforts in granite are dead on arrival, some of Koons’ sculpture of the past two decades is impossible to refuse. You don’t need to agree that a giant polyethylene cat is as gratifying as the Belvedere Apollo to be transfixed by his giant polyethylene cat. You also don’t need to agree that his work routinely touches upon large questions of, as he puts it, “what the human experience is, what it means, what it can be,” so long as he pulls off feats of material glory like his aluminum mountain of Play-Doh.

Even as he heads into his 60s, we can count on Koons to stay in touch with his inner child. In 2002 he married Justine Wheeler, an artist who worked in his studio, and today they have six young children. Their principal residence is in Manhattan, but they spend most weekends with the kids on an 800-acre (320 hectare) farm near York. It used to belong to Koons’ maternal grandparents but went out of the family until he repurchased it in 2005. Ever since, he’s been restoring it to match his youthful memories–a world where he can be a child among his children.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com