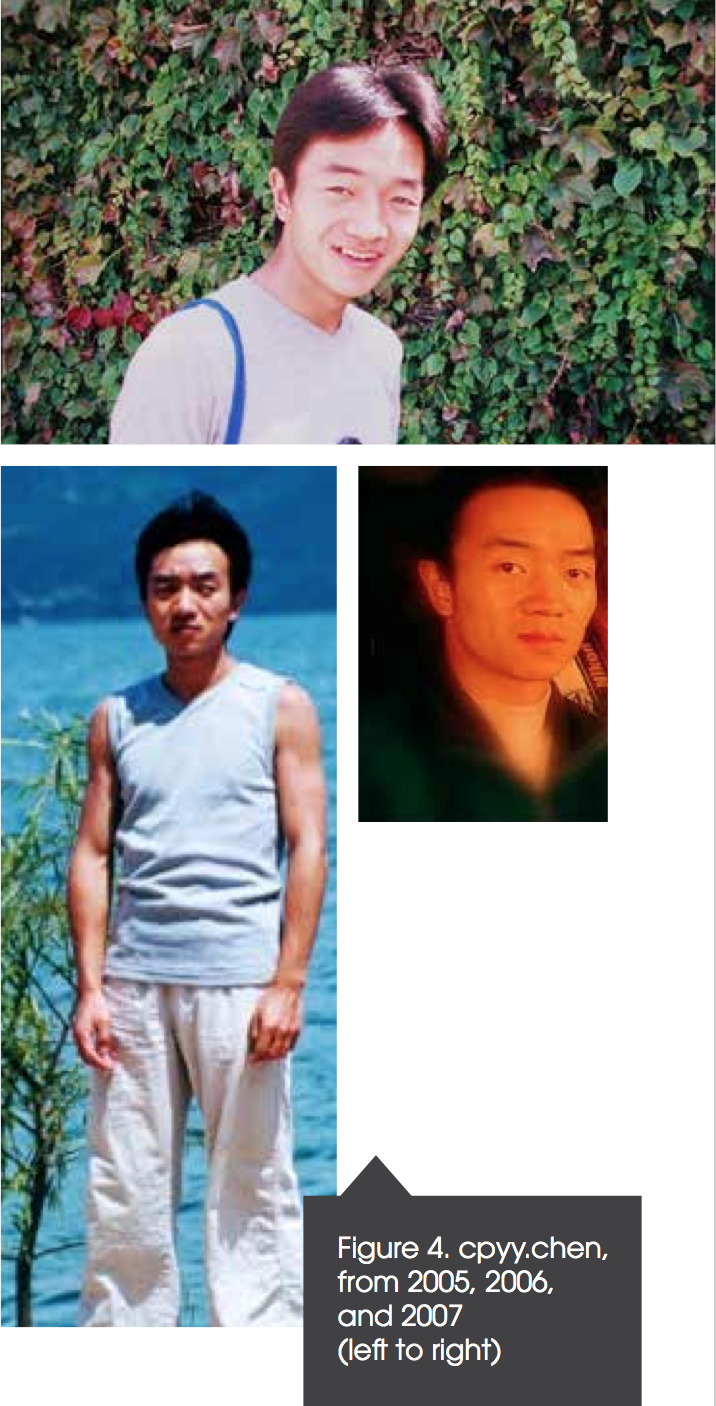

There are many photographs of Chen Ping. In one, he’s scarfing down pastries at a birthday party. In another, the camera catches him mid-laugh, standing in front of an ivy-covered wall. Chen photographed his dorm room, too, with bottles of rice liquor splayed across a desk next to a potted plant, clothes hanging in the corner. In a garden, he took photos of his girlfriend, catching a pleasant smile.

The photos are curious because Chen was supposed to be one of the faceless warriors in an emerging global cyber-war, according to researchers at the Internet security firm CrowdStrike. But the 35-year-old former resident of Shanghai left a trail of clues and photographs that researchers say led back to a People’s Liberation Army headquarters, where a covert team of Chinese hackers has been attacking telecommunications and satellite companies in the U.S. for at least seven years. The CrowdStrike researchers nicknamed Chen’s hacking ring “Putter Panda.”

To the Chinese army, the hackers are known only as People’s Liberation Army Unit 61486 — a group that a U.S. government official confirmed in an interview with TIME was responsible for cyber-attacks on American companies. The group came to light in a recent New York Times story. And Project 2049, a nongovernmental think tank based in Arlington, Va., claimed in a 2011 report that Unit 61486 was involved in the interception of satellite communications, as well as the acquisition of research in satellite imagery. But it wasn’t until researchers at CrowdStrike tracked down the hacker called Chen that the world got an unprecedented inside look at one of China’s notorious cyber-attack units.

CrowdStrike is part of a fast-growing group of young companies including FireEye, Sourcefire, OpenDNS and others that are challenging more established players for a bigger claim to the $67 billion cyber-security industry. They’re doing that by tracking state-sponsored hackers like Unit 61486 and independent cyber-criminals alike, anticipating their attacks before they happen. According to research firm Gartner, the security-technology industry is expected to grow to $86 billion by 2016. As cyber-attacks from state-sponsored hackers simply become a cost of doing business for many American companies, security researchers are making money by stalking hackers through fiber-optic cables and web domains to their computers back home.

At CrowdStrike, a 20-person team of researchers used technology ranging from the cutting-edge to the prosaic to find Chen’s Shanghai office address, and then monitored him and his colleagues. Companies like CrowdStrike say they are the first line of defense for U.S. companies’ intellectual property. “This is like real-time warfare,” says George Kurtz, co-founder of CrowdStrike. “We’re able to see exactly what they’re trying to do, where they’re trying to go and able to stop them in their tracks.”

Digital Warfare

It’s become increasingly clear that the future of espionage will be played out through fiber-optic cables, web servers and other computer systems. Cyber-espionage costs U.S. companies $30 billion each year in lost intellectual property alone, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), and that doesn’t include the cost of cleaning up and recovering information. The FBI notified 3,000 U.S. companies that they had been hacked in 2013 by cyber-criminals or Chinese state actors. “We remain concerned that Chinese authorities continue to use cyber-operations to steal information and intellectual property from U.S. entities for the purpose of giving Chinese companies a competitive advantage,” a senior administration official told TIME.

Cyber-attacks are not a one-way street, of course. The National Security Agency is believed to have developed powerful capabilities to strike foreign entities. The U.S. badly disrupted Iran’s nuclear program through targeted network attacks in 2009 and 2010, according to multiple reports at the time. And the Edward Snowden leaks revealed that the NSA is engaged in the surveillance of email and telecommunications around the world, with the primary aim of bolstering U.S. national security — rather than the bottom lines of U.S. companies.

But security experts say Chinese cyber-programs are broadly focused on disrupting foreign businesses, taking valuable intellectual property and sensitive bidding information that Chinese corporations can use to their advantage. After hacking American manufacturers and corporations, the PLA passes on information to Chinese state-owned enterprises, often for a fee, says Jim Lewis, the director of strategic technologies at CSIS and a former foreign-service officer with the Departments of State and Commerce. Chinese corporate hacking is a robust industry, not limited to stealing foreign commercial secrets but also involves Chinese companies trying to best each other. “The Chinese are far and away the global leaders in terms of commercial espionage,” says Lewis. “The PLA will steal the F-35 plans, but they’ll also steal paint formulas or soap formulas.”

By keeping tabs on hackers and publishing open reports, private security companies like CrowdStrike may also be playing a role in pushing the U.S. to prosecute hackers. Last year, security firm Mandiant identified a different Chinese army group, Unit 61398, that allegedly hacked a broad swath of U.S. companies. Then in May, the Justice Department made history by charging five individuals from Unit 61398 for hacking U.S. businesses. The Chinese government denied the Justice Department’s claims, calling the accusations of hacking “made up” in official statements. “China is a staunch defender of network security, and the Chinese government, military and associated personnel have never engaged in online theft of trade secrets,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Qin Gang said last month.

CrowdStrike had long been keeping tabs on Chen’s Unit 61486 for its customers, but it wasn’t until the Chinese government’s denials that the firm decided to publicize its findings. “We put out the report specifically based on the denials of the Chinese government after the Department of Justice indictment,” says Kurtz. “We kind of got fed up and said, O.K., here’s a totally separate group than the one that was focused on by the DOJ and here’s all the proof.” CrowdStrike says it alerted the U.S. government before it released its report.

Unit 61486 began exploiting vulnerabilities in Microsoft and Adobe coding as early as 2007, hacking satellite and telecommunications companies, says Adam Meyers, head of intelligence at CrowdStrike. “There was a massive number of targets and data that were hit,” Meyers says.

Following Chen’s Tracks

Meyers’ team at CrowdStrike compiled a startling amount of information about Chen Ping (who happens to have a very common name), the alleged member of Unit 61486. CrowdStrike first looked at remote web domains being used to direct and control malware on infected computers. The web domains had to be registered, and the team found that many of the domains were registered under the same email addresses. One registered at least a half-dozen of the website domain names; someone with another email address registered several as well.

The big find, however, was a certain “cpyy” — operating with two major email providers — who had registered a large number of the remote malware-control domains. The CrowdStrike team cast a wide net to find cpyy, trailing the nom de guerre to a personal blog by a registrant named Chen. Chen’s blog profile, all in Chinese, stated he was born on May 25, 1979, and that he worked for the “military/police.” Another cpyy blog listed the identical birthdate and noted that the user lived in Shanghai. The blog said, “Soldier’s duty is to defend the country, as long as our country is safe, our military is excellent.” Meyers’ team was fairly certain it was the same Chen, given that same handle appeared repeatedly, but they needed more evidence to connect him to the PLA.

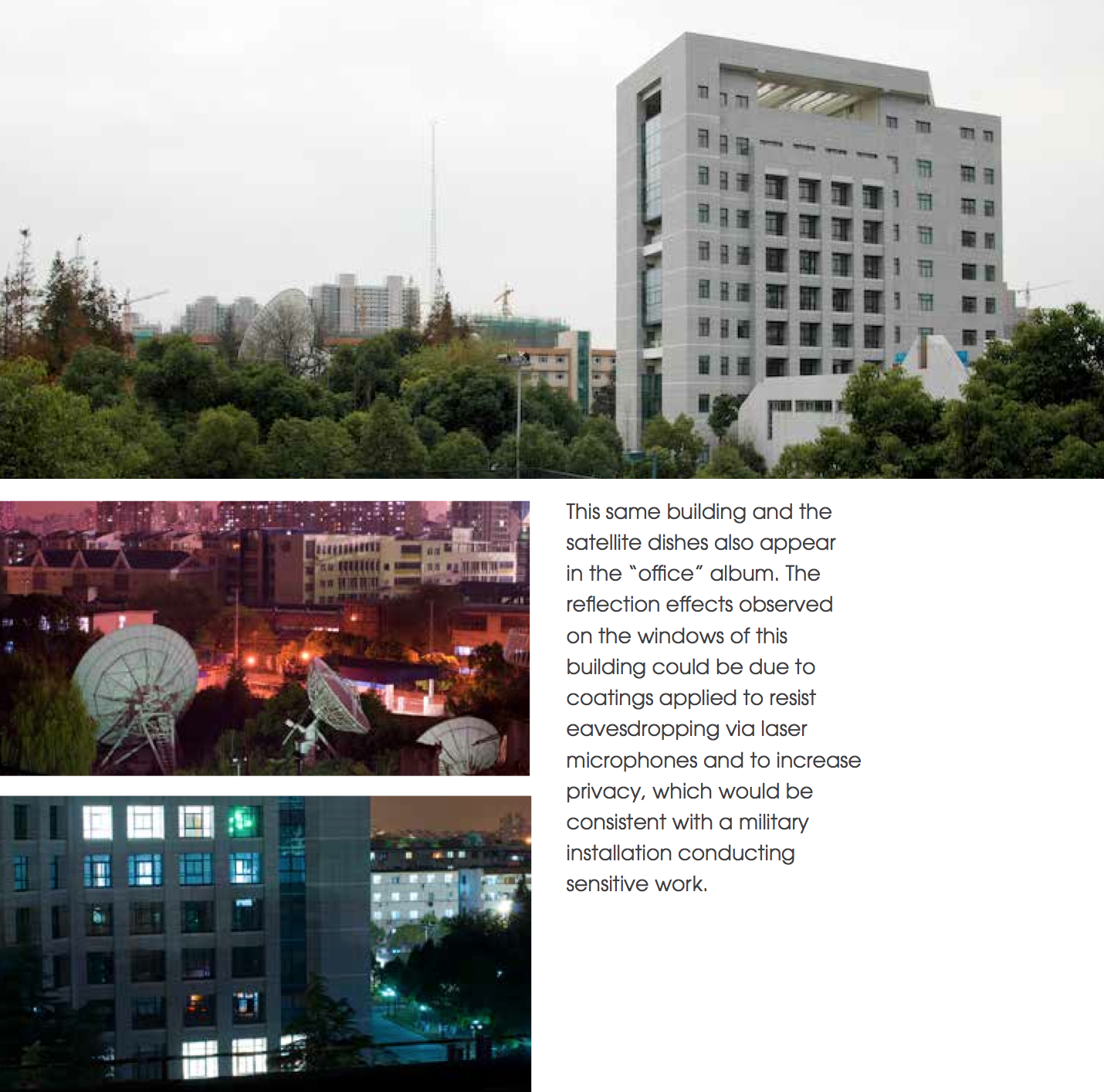

Sifting through the public records that connected Chen’s online profiles, the team found photos he posted. He shot with a Nikon, CrowdStrike said. He had a Google Picasa album with some of the same pictures in his blog post. Photos captioned “me” showed a young man with a bemused smile, laughing in a tent with a friend, doing pull-ups in front of a group of soldiers and playing guitar in a field. He took artistic photographs of objects in what he called “office.” According to Meyers, the photos revealed Chen was not just one hacker acting alone: in one, PLA hats were stacked in the background, and another photo of satellite dishes in his album “office” indicated ties to army signals intelligence.

Chen was sloppy. When he registered one of the malware-control web domains, he input a physical address that tied him to a Shanghai building near the massive satellite dishes from his photos, Meyers says. Close analysis of overhead satellite imagery linked all the buildings in Ping’s photos to the very same address. And the CrowdStrike team found a Chinese website that listed the same address as a PLA building for Ping’s unit, 61486.

That implicated Chen, the unit and by extension, the Chinese government, according to CrowdStrike. “These guys are human,” says Meyers. “Sometimes when you’re behind the keyboard and you walk away from it, you forget there are other people out there who are going to be looking for you.” (Chen did not respond to request for comment to his listed email addresses. China’s Foreign Ministry did not return requests for comment.)

Covering Up the Trail

When the Justice Department charged the five alleged Chinese hackers in May with stealing trade secrets from U.S. companies, it named the hackers in the indictment and published photos of them. To some observers it was not so much an attempt to prosecute the accused hackers, who would have to be extradited from China, but more of a clear message to the Chinese army: We know how to find you.

“Cyber-theft is real theft and we will hold state sponsored cyber-thieves accountable as we would any other transnational criminal organization that steals our goods and breaks our laws,” John Carlin, Assistant Attorney General for National Security, said in a statement in May.

Experts say that going forward, the Chinese are likely to be more careful about leaving fingerprints behind in cyber-attacks.

Chen had been moved out of Shanghai to Kunming, Yunnan province, as early as 2011, CrowdStrike said, where according to Project 2049, the nongovernmental think tank, his army bureau (the 12th) has a facility. After Meyers’ team released its report, all the data that had been used to find Unit 61486 was scrubbed from the Internet, and Ping seemed to disappear. “They cleaned up all of his online presence real quick after that report came out,” Meyers says. “The next day, all of his sites were gone.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com