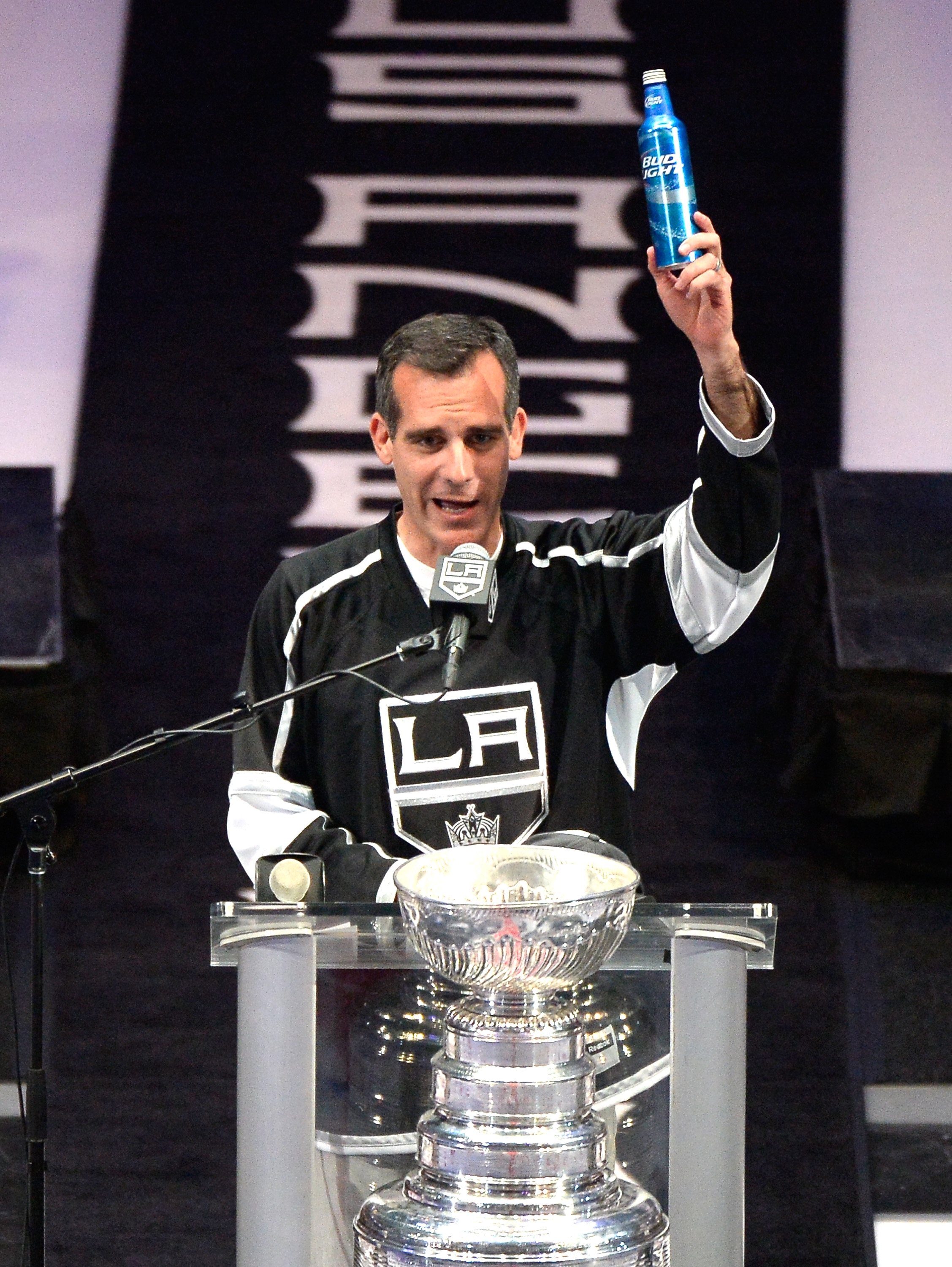

In making headlines after declaring at a hockey rally, “This is a big fuckin’ day,” was Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti having a big fuckin’ day himself? Or rather, one for the f-word?

There are real data now to help answer such a question. Relatively recent technologies — cable television, satellite radio, and social network media — provide us with a not-too-unrealistic picture of how often people swear in public and what they say when they do. Before these new forms of reporting, the media provided a fairly sanitized view of spoken English. Newspapers today still swerve to avoid swearing, opting for euphemisms like “_____,” “PG-rated expletive,” or “an eight-letter word for animal excrement,” instead of telling us what was really said. Fortunately, YouTube now offers people like me, who study language and profanity, a more accurate picture.

Are widely reported acts of swearing by public figures like Garcetti’s typical or not? And are the rest of us any different? How frequently do regular people swear and what do we say?

We language scientists attempt to answer these questions. In one study reported in the journal Science, less than one percent of the words used by participants (who were outfitted with voice recorders over a period of time) were swear words. That doesn’t sound like very much, but if a person says 15,000 words per day, that’s about 80 to 90 “fucks” and such during that time. (Of course, there’s variability–some people don’t say any swear words while other people rival David Mamet). More recently, my research team reported in The American Journal of Psychology that “fuck” and “shit” appeared consistently in the vocabularies of children between 1 to 12 years of age. And you shouldn’t worry — there is no evidence to suggest a swear word would harm a youngster physically or psychologically.

So please, let’s not be shocked by swear word statistics, or by politicians swearing in public. Politicians get caught swearing all the time. In 2000, George W. Bush referred to a New York Times reporter as a “major league a–hole.” In 2004, Vice President Dick Cheney told Vermont Senator Pat Leahy to go [bleep!] himself on the floor of the U.S. Senate. In 2010, Vice President Joe Biden called the passage of President Obama’s health care legislation “a big fucking deal.” (Granted, it was meant to be said more privately than the mic conveyed.) I place Mayor Garcetti’s profane celebration of the Kings’ Stanley Cup in the Biden category of Happiness-Induced Cussing.

But what happens when the viewer at home encounters these expletive-laced speeches on their TVs or the Internet? Some viewers take it personally, taking it as classless, or moral degradation; I would argue they’re only thinking of the historically sexual meaning of the word “fuck.” But both Garcetti and Biden (along with Bono at the Golden Globes) used “fucking” as an intensifier, not as a sexual obscenity. Yet most swear words are used connotatively (to convey emotion).

The Federal Communications Commission waffles on what to do about Garcetti-style “fleeting expletives.” Fox Sports apologized for Garcetti’s “inappropriate” speech but it’s not clear if Fox will be fined by the FCC. (My best guess: probably not, since Obama’s commissioners are dovish on profanity.) The FCC ruled less liberally during the Bush years when conservatives had more sway. It’s interesting that people don’t complain as much about alcohol ads in professional sports. Alcohol can kill you, but swearing won’t; swearing might even help you cope with life’s stressors, according to recent research.

Older generations who are less understanding of technology may perceive that profanity represents a change in language or societal habits, even when that is not the case. Swearing by people in positions of power has always been there; it just used to be better hidden. We have to learn to accept that we are now going to hear more Garcettis.

And there’s something else you might have noticed. The day after any swearing incident nothing happens. No one has to be hospitalized or medicated. Yes, sensibilities may get jangled, but coping with slight deviations from the expected is part of life. No one, not even your mother, dies from hearing “fuck.”

Timothy Jay is a professor of psychology at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts. He has published numerous books and chapters on cursing, and a textbook for Prentice Hall on The Psychology of Language. This piece originally appeared at Zocalo Public Square.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com