In the 1960s, before the Beatles made singer-songwriters fashionable, few people cared who wrote the songs they loved. The composers’ names were just part of the small print on a 45 r.p.m. disc. And if people know the writer behind such girl-group classics as “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “One Fine Day” and “I’m Into Something Good,” or The Drifters’ “Up on the Roof” or Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” it’s probably because their composer, Carole King, eventually became a pop star — permanent brand for her songs about love, longing and romantic renewal.

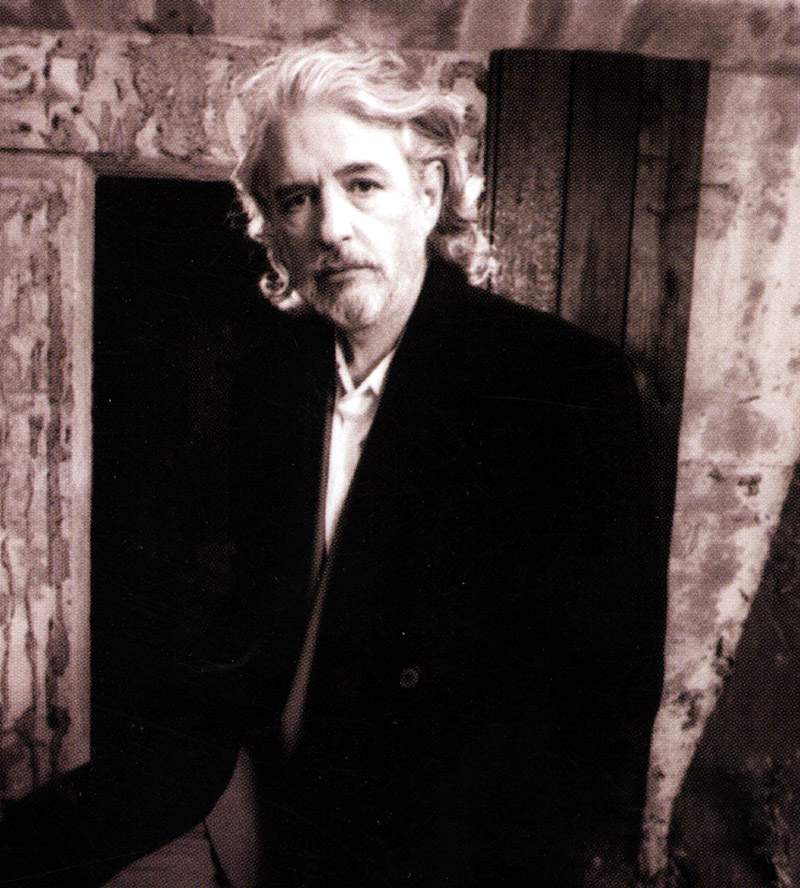

King wrote the music for all those perennials, but Gerry Goffin, her husband in the ’60s, wrote the words. Goffin, who died at his Los Angeles home June 19, at 75, never achieved his ex-wife’s renown. His triumph was almost private: the accomplishment of giving performers such as the Monkees (“Pleasant Valley Sunday”) and balladeer Steve Lawrence (“Go Away, Little Girl”) lyrics that expanded the pop lexicon and often reached a plainspoken profundity. After he and King parted professionally and maritally, Goffin teamed with Michael Masser to write poignant hits for Diana Ross (“Do You Know Where You’re Going To”) and Whitney Houston (“Saving All My Love for You”).

A look at Goffin’s lyrics upends the common wisdom that pre-Beatles adolescent pop was all banal optimism conveyed in moon-June-spoon doggerel. His protagonists were likely to be impaled by love’s harpoon, or swept away by a romantic typhoon, or treated like a buffoon, or finding solace only when marooned. Goffin was eerily in sync with the convulsions kids feel during first love, first sex and first breakup. As King said yesterday in tribute to Goffin, “His words expressed what so many people were feeling but didn’t know how to say.” Their songbook endures, in millions of memories and in the current Broadway hit Beautiful: The Carole King Musical — which is nearly as much the Gerry Goffin Musical.

(READ: Richard Zoglin on Beautiful: The Carole King Musical)

Born in Brooklyn on Feb. 11, 1939, and raised in Queens, Gerald Goffin wanted to write Broadway shows. But as a chemistry major at Queens College he met a freshman, Carol Klein, who was a budding composer in the pop idiom. (Her friend Neil Sedaka had written “Oh Carol” for her.) They married in 1959, when she was 17 and pregnant with their first child, who would grow up to be singer-songwriter Louise Goffin. Klein, already a minor recording artist, took the stage name Carole King.

Working in the cramped, smoky warrens of 1650 Broadway, up the block and across the street from the legendary Brill Building, Goffin and King were one of a remarkable trio of young, Jewish, married songwriting teams. Barry Mann (born two days before Goffin) and Cynthia Weil (born Oct. 18, 1940) would compose a flock of lasting hits: “Here You Come Again” for Dolly Parton, “Just a Little Lovin’ (Early in the Morning)” for Dusty Springfield, “On Broadway” for The Drifters, “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” for The Animals and, for The Righteous Brothers, “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” which received more airplay than any song from the 20th century.

Another duo, Jeff Barry (born 1938) and Ellie Greenwich (born five days after Weil), composed a series of pile-driving classics for producer Phil Spector — “Be My Baby,” “Da Doo Ron Ron,” “River Deep, Mountain High” — plus “Doo Wah Diddy Diddy,” “Chapel of Love” and “Leader of the Pack.” If kids in the early ’60s had American songs running through their heads, they could thank these three teams of prodigy composers, who wrote so acutely about young love and loss because they were practically teens themselves.

(TRY TO FIND: a Goffin-King song on the all-TIME 100 Songs list)

Goffin and King’s first hit is one of their immortals: the 1960 “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” for the Shirelles. A woman has just given herself to her boyfriend and, in the postcoital afterglow — or rather, in her gnawing unease — wonders if he’ll stick around for love now that he’s had the sex. A series of questions lingers between doubt and guilt: “Is this a lasting treasure / Or just a moment’s pleasure? / Can I believe the magic of your sighs? / Will you still love me tomorrow?” The song went to No. 1 and cued several reassuring “answer” songs, none of them penned by Goffin. On Broadway it serves as the virtual theme of Beautiful, played three times during the show.

For the men in Goffin lyrics, women were often precocious temptresses: little girls with dangerous charms. The 1960 “When My Little Girl Is Smiling,” gorgeously produced by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller for Ben E. King and The Drifters, allows the hapless male to react with a smile and a shrug: “Why should I want to fight / When I can hold her tight? / I just don’t care who’s right or wrong.” (Nice internal rhyme.) The mild-sounding “Go Away, Little Girl” is really the whispered plea of a married man — or possibly a pedophile — fighting the impulse of his attraction to a flirtatious young female. “When you are near me like this, / You’re much too hard to resist. / So, go away, little girl, before I beg you to stay.” A no. 1 single for Lawrence in 1962, this creepy renunciation ballad went to the top of the pops nine years later for Donny Osmond.

(READ: A tribute to rock ‘n roll songwriter-producer Jerry Leiber)

Goffin’s ultimate SM lyric — from the masochist’s point of view, of course — is the 1961 “He Hit Me (It Felt Like a Kiss).” Eva Boyd, the babysitter for Louise Goffin, told them that her boyfriend had beaten her and, when asked why she stayed with him, she explained that his fury proved his affection. Goffin expanded that plaint into a playlet of a woman betraying her man and doomed to savor the consequences: “He couldn’t stand to hear me say / That I’d been with someone new. / And when I told him I had been untrue / He hit me, and it felt like a kiss. / He hit me, and I knew he loved me. / If he didn’t care for me / I could have never made him mad. / But he hit me, and I was glad.”

King composed a minor-key dirge for this sad, sick testimony, and Spector arranged the song with sepulchral strings, as if it were being sung from the grave of an abused woman. Rarely played on the radio, and eventually disowned by King, “He Hit Me” found adherents decades later: it was covered by Courtney Love and her band Hole, played at the end of a Mad Men episode (“Mystery Date”) and just this month is referenced in Lana Del Rey’s song “Ultraviolence.” Boyd, the babysitter, didn’t have to wait that long for validation. Goffin and King wrote the perkily droning, emotionally uncomplicated dance tune “The Loco-Motion” for her, and, as Little Eva, she took it to No. 1 in 1962.

(READ: Sacha Geffen’s review of Lana Del Rey’s “Ultraviolence”)

Goffin could force himself to write angst-free lyrics, as he demonstrated in “The Loco-Motion” and “I’m into Something Good,” a modest 1964 success for The Cookies that became an international hit when covered by Herman’s Hermits the following year. But even the bright uptempo numbers could hold a gloomy subtext. The Chiffons’ “One Fine Day,” which bubbles along with a chirpy refrain and dooby-doo-wahs, is essentially the wistful prayer of a rejected girl: “One fine day, we’ll meet once more / And then you’ll want the love you threw away before / One fine day, you’re gonna want me for your girl.”

Sometimes a Goffin character can find happiness only by retreating into solitude. “Up on the Roof” — a kind of “answer” song to Mann and Weil’s “Uptown,” about a guy who’s a wage slave downtown but a romantic king when he comes home — imagines a man whose idea of Heaven is the top of his tenement: “On the roof it’s peaceful as can be / And there the world below can’t bother me.” King provided an ethereal musical setting for Goffin’s lyric of escape; and the song, performed by Rudy Lewis and the Drifters, hit the top five on the mainstream and R&B charts in 1962.

As Brill Building pop went out of favor, and pop stars started writing their own songs, Goffin turned from girl groups to divas as his interpreters. For Aretha Franklin, he and King wrote “A Natural Woman,” a song of redemption from the depths: “When my soul was in the Lost and Found, / You came along to claim it. / I didn’t know just what was wrong with me / ‘Til your kiss helped me name it.” The Goffin-Masser “Saving All My Love for You,” written in the ’70s for Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis and covered in a 1985 top-10 version by Houston, portrays a married man’s mistress who dares to hope for fulfillment: “A few stolen moments are all that we share. / You’ve got your family, and they need you there. / Oh, I’ve tried to resist being last on your list / But no other man’s gonna do, / So I’m saving all my love for you.” Another Goffin dreamer, another lovelorn loser.

(READ: Corliss’s 1987 appraisal of Whitney Houston, the Prom Queen of Soul)

He wrote his most haunting, mordant lyric for the 1975 Diana Ross film Mahogany. “Do You Know Where You’re Going To,” another No. 1 hit, raised the age bar from fretful teen to disillusioned adult, and the stakes from failed romance to existential chill. “Now looking back at all we’ve planned / We let so many dreams just slip through our hands. / Why must we wait so long before we’ll see / How sad the answers to those questions can be?”

Goffin was back where he began, in “Will You Love Me Tomorrow”: using the pop-ballad form to offer hard answers to dewy questions, and often saying that life’s most perplexing riddles had no comforting resolutions. King put the hummable lilt in many of their songs, but Goffin educated young listeners to the complexity of love and loss. He wasn’t just the guy who put simple words to her lovely music. He was a prime ’60s poet of teen yearning.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com