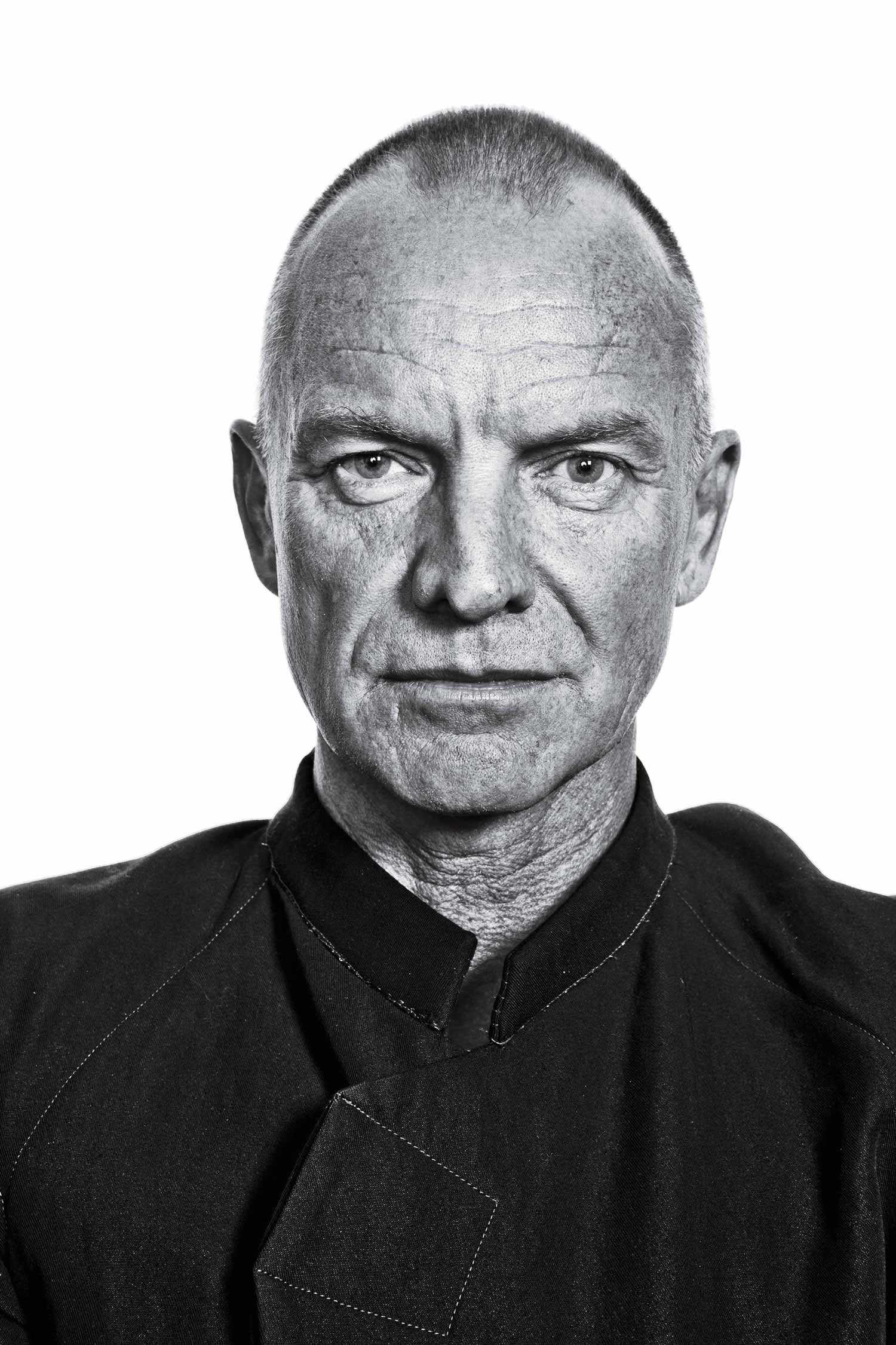

As the superstar front man of the Police, Sting wrote nearly every song on the band’s five hit albums from 1978 to 1983. For the next two decades, as a solo artist, he issued seven more albums, scored 11 hit singles and won 10 Grammys. Then the songs stopped.

So many years had passed since he’d written his last notes that Sting began to wonder if his muse was gone for good. But rather than hang up his pen, he took on a new challenge in the face of writer’s block: creating a Broadway musical. “I had no interest in tailoring songs for Top 40 radio, for 14-year-old girls or boys,” he tells TIME. “I’m a 62-year-old man. Where is the arena to present my work? It’s not radio anymore.”

The show he wrote, The Last Ship, debuted at Chicago’s Bank of America Theatre on June 10, a precursor to a Broadway engagement this fall. Sting summoned the tale from a childhood that took place literally in the shadows of enormous freighters being built at the end of his now demolished street in Wallsend, a port town near Newcastle in northeastern England. His grandfather was a shipwright, and others in the family worked in the yards or on the ships. Growing up as Gordon Sumner, he says, “I feared that world was my destiny,” until a “battered old guitar” became his “accomplice, a co-conspirator to escape.”

Sting returned to this world with eyes made sharp and clear by the passage of time and distance. “I’m not romanticizing the shipyards. These were tough and dangerous jobs, and the toxic chemicals those guys worked with were appalling,” he says. “But the men could point to something and say, ‘I built that.’ And they had a sense of common purpose amidst the hardship. That’s a loss.”

In The Last Ship, a self-exiled man returns home and finds his community about to vanish. They will build one last ship to show the world what they do and who they are. “It’s about a ridiculous, quixotic, Homeric gesture,” Sting says. “In a way, so is creating a musical.”

“A Theatrical Assassin”

In 2009, with his concept in mind, Sting met with producer Jeffrey Seller, who had won Tonys for shows that seemed unlikely ever to reach Broadway, let alone become hits: Rent, Avenue Q and In the Heights. Seller was excited by Sting’s “unlikely and beautiful notion” but wanted to make sure the pop star understood what he was getting into. “I said, ‘Creating a musical is very frustrating and has many roadblocks and will take longer than you think,'” Seller recalls. “He said, ‘That sounds just like being in a rock band.'”

Their meeting reawakened Sting’s voice. “It opened the floodgates, and 40 or 45 songs just poured out of me almost fully formed,” he says, “as though they’d been bottled up inside.”

Songs like “The Last Ship” tell the story of the tight-knit community; others have a strong autobiographical flavor. In “Dead Man’s Boots” the father sings, “It’s time for a man to put down roots and walk to the river in his old man’s boots.” But the son eventually responds, “Why in the hell would I do that? And why would I agree?,” evoking the showdown between Sting, who wanted to attend a school where he could study Latin and literature and art, and his milkman father, who thought the lad should go to technical school, as he had.

Thanks to his mother, young Gordon won. She was also key in providing musical inspiration: she kept albums by Elvis Presley and Little Richard around the house, not to mention the cast recordings from productions of Oklahoma! and West Side Story that gave the future composer his first taste of Broadway musicals.

With a rock legend telling a personal story, Seller knew he’d need to assemble a creative team who could collaborate with Sting as peers–“people who would not be in awe, who could say, ‘That song’s not good enough’ or ‘That’s not the right moment for it.'” So Seller brought in director Joe Mantello, who has won two Tony Awards and a Drama Desk Award for Wicked and Take Me Out, among other shows. John Logan, who won a Tony for Red and earned Oscar nods for screenplays such as Gladiator and Hugo, was tapped to shape the book.

Sting, who admits he was used to being “more of a dictator in a band,” says the musical is the most collaborative thing he has ever attempted. And his creative partners found him open to their suggestions. “He liked being challenged,” Mantello says. “I said to him, ‘Every line has to argue for its existence,’ and he became a theatrical assassin.”

The only time the rocker faltered was when he was told to jettison one of his favorite tunes, “Practical Arrangement,” about an older man falling for a younger woman. To enhance dramatic tension in the show’s love triangle, the male character had to be rewritten, says Sting, “to be as viable and virile as his rival.” Having identified with the aging lover, Sting initially resented this young replacement, but eventually he acquiesced and wrote a new song, “What Say You, Meg?” “Practical Arrangement” joined a handful of other songs excised from the original score. “I’m half-seriously thinking of putting on a show of me singing all the songs that didn’t make it into the musical,” says Sting.

Handing off his songs to other performers was easier than expected, and Sting was delighted by the depths a full theatrical cast added. The title song sounds haunting and elegiac in his solo rendition, but in the production it fills out with a grandeur worthy of the community’s quest. The chorus’ backing vocals convey the majestic rolling and crashing of waves out at sea.

In rehearsal, Sting sits quietly, leaning back, arms folded, observing all the details. He offers tips on how best to sing his songs, but “with the proviso that they can say, ‘F-ck off, Sting, I’m doing this my own way.'” He can’t help singing along, though he also passes on a note to urge the actors to hit the t in the word last, so it doesn’t blur into the word ship. Logan praises Sting’s enthusiasm, noting that he even shows up for choreography rehearsals, though the rocker acknowledges that it’s probably more out of obsession that he focuses on The Last Ship with, you might say, every breath he takes. “I go to sleep with this show. I dream about it. I wake up with it,” he says. “I make at least three points a day, even if it’s just a change of tense or of a pronoun.”

He had braced himself for a bigger overhaul during rehearsals. “I was fully expecting to perform major surgery, an amputation here, a transplant there,” he says. “Touch wood again I haven’t had to do that.” (So cool and calm, Sting doesn’t appear to be the superstitious type, but the first time he said touch wood during the interview, he actually reached below the glass table to tap on its wooden leg.)

He hopes mainstream Broadway theatergoers will be willing to listen to this unusual saga, especially those who might have expected a jukebox musical of his greatest hits. “This isn’t A Chorus Line, but I think it’s a story worth telling,” he says. “I’ve never pandered to the lowest common denominator. I have a good audience, and I’m supposed to challenge them. I always expect the audience to make the journey with me.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com