You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

On the sun-baked plaza behind the U.S. Capitol, TV vans hummed like hungry insects. Marching in disorderly array up the steps to the Senate cham ber came group upon group of summer tourists, sunglasses on and cameras slung high. Inside, the Senate gallery was packed.

Only an hour remained before the critical vote. Now Majority Leader Mike Mansfield of Montana rose, and in soft tones spoke in favor of cloture; if approved by two-thirds of the Senators present and voting, it would bring to an end the longest filibuster in Senate history. “The Senate,” Mansfield said, “now stands at the crossroads of history, and the time for decision is at hand.”

He read aloud a letter he recently received from a Montana mother of four.

“When I kiss my children good night,” she wrote, “I offer a small prayer of thanks to God for making them so perfect, so healthy, so lovely, and I find myself tempted to thank him for letting them be born white. Then I am not so proud, neither of myself nor of our society, which forces such a temptation upon us.”

“The Question Is . . .” Mansfield’s time ran out, and he relinquished the floor to Georgia’s Richard Brevard Russell, leader of the Democratic bloc that had been filibustering against the most far-reaching civil rights bill in U.S. history. Russell was about to go down in defeat, and he knew it. But his final-hour plea was urgent. Said he: “If this bill is enacted into law, next year we will be confronted with new demands for enactment of further legislation in this field, such as laws requiring open housing and the bussing of children. The country is becoming enmeshed in a philosophy that can only lead to the destruction of our dual system of sovereign states in an indestructible Union.”

Russell gave way to Minnesota Democrat Hubert Humphrey, the Johnson Administration’s floor manager for the bill. In his lapel Humphrey wore a red rose like a battle standard. “The Constitution of the United States is on trial,” he said. “The question is whether we will have two types of citizenship in this nation, or first-class citizenship for all.”

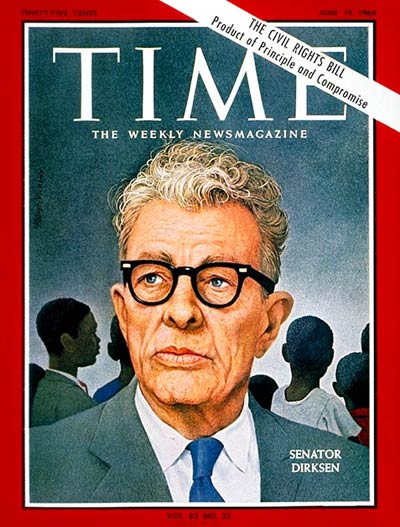

Only 15 minutes remained before voting time. Illinois Republican Everett McKinley Dirksen, 68, the Senate’s minority leader, arose slowly from his front-row desk. He was the man most were waiting to hear, not merely because he is the Senate’s most practiced and professional orator but largely because he is the shrewd, patient negotiator whose efforts, perhaps more than anyone else’s, had made a favorable cloture vote likely. With great deliberation Dirksen took off his tortoise-shell spectacles, revealing his sad, bloodhound eyes underlined by deep, dark pouches. In his massive left hand, its little finger flourishing a green jade ring, he held a twelve-page speech he had typed the night before on Senate stationery.

“The Time Has Come.” “Mr. President,” said Dirksen in that voice that turns hoarseness into authority, “it is a year ago this month that the late President Kennedy sent his civil rights bill and message to the Congress.” In the gallery an elderly Negro minister craned forward and cupped an ear. Dirksen continued: “Sharp opinions have developed. Incredible allegations have been made. Extreme views have been asserted. There has been unrestrained criticism about motives.” As for himself, Dirksen noted, “I have had but one purpose, and that was the enactment of a good, workable, equitable, practical bill having due regard for the progress made in the civil rights field at the state and local level. I am no Johnny-come-lately in this field. Thirty years ago, in the House of Representatives, I voted for anti-poll-tax and antilynching measures. Since then, I have sponsored or co-sponsored scores of bills dealing with civil rights.

“The time has come,” said Dirksen, “for equality of opportunity in sharing in government, in education, and in employment. It will not be stayed or denied. It is here.” The chamber was dead-quiet. “America grows. America changes. And on the civil rights issue we must rise with the occasion. That calls for cloture and for the enactment of a civil rights bill.”

Dirksen jabbed an index finger at his colleagues on both sides of the aisle. His voice rose to a slightly higher pitch, taking on an extra tone of persuasiveness. The Senate, he said, had a “covenant with the people. For many years each political party has given major consideration to a civil rights plank in its platform. Were these pledges so much campaign stuff, or did we mean it? Were these promises on civil rights but idle words for vote-getting purposes, or were they a covenant meant to be kept? If all this was mere pretense, let us confess the sin of hypocrisy now and vow not to delude the people again.”

The Vote. It was precisely 11 a.m., the time set to vote. While Dirksen was still talking, the presiding officer, Montana Democrat Lee Metcalf, brought down his gavel. “Is it the sense of the Senate that the debate shall be brought to a close?” Metcalf asked and ordered the yeas and nays.

“Mr. Aiken,” intoned the tally clerk.

“Aye,” voted Vermont’s Republican Senator George Aiken.

“Mr. Allott.”

“Aye,” said Colorado Republican Gordon Allott.

A moment of pathos came when the clerk arrived at the name of California Democrat Clair Engle, who has undergone two brain operations and has not appeared in the Senate since April. For this occasion, Engle, smiling gallantly, had been wheeled into the chamber. When the clerk called his name, Engle tried to speak, but could not. Finally he lifted his left arm, pointed at his head, and nodded his aye.

Another closely watched vote was that of Arizona’s Barry Goldwater, the leading candidate for the Republican presidential nomination. Goldwater had long been critical of the civil rights bill, arguing that brotherly love cannot be legislated into the hearts of men. Of course, the bill attempts to do no such thing; it merely seeks to ensure to all Americans the equality under the law that is their birthright. In recent days Goldwater had indicated that he might wind up voting for the bill if it was amended according to his tastes. But that did not mean he would support cloture. He now answered the roll call with a brusque no.

On and on went the vote. When it reached Delaware Republican John Williams, it stood at 66 for cloture, 20 against. Williams’ soft aye made the two-thirds majority required for cloture, and victory. “That’s it,” cried a Senator. Newsmen sprinted to telephones that had been held open. Mike Mansfield sagged in relief. Dick Russell, grim as death, scribbled fitfully on a yellow pad. Out of the cloakroom hobbled Arizona’s Carl Hay den, 86, president pro tempore of the Senate and the man who stands next only to House Speaker John McCormack in the line of succession to the U.S. presidency. Although a longtime foe of cloture, Hayden this time had told Mansfield he might vote for it if he was really needed. He wasn’t. “It’s all right, Carl,” cried Mansfield. “We’re in.” Hayden voted no.

At last the clerk read the tally. It stood at 71 for cloture, 29 against. With four more votes than were required, the U.S. Senate for the first time in its history had invoked cloture against a civil rights filibuster. On the issue, all 100 Senators had taken their stand. And in so doing, they cleared the way for certain passage of the bill.

The measure’s previous life had been fraught with difficulties. No sooner had he taken over as President than John Kennedy, who had campaigned on a strong and effective civil rights pitch, let it be known that he would deal with civil rights through administrative, not legislative action. One obvious Kennedy fear: that a civil rights bill sent to Congress would prove politically harmful by dramatizing, once again, the fact that Capitol Hill Democrats were far more deeply divided than Republicans on the issue.

Flesh on the Skeleton. For two years congressional Republicans chided Kennedy for his failure to present a civil rights legislative program. Finally, in January 1963, a group of House Republicans introduced their own broad-gauged measure. One month later, President Kennedy sent his first major civil rights message to the Hill. It was terribly thin, asking for federal court-appointed voting referees to determine applicants’ qualifications while their voting suits were pending, an extension of the Civil Rights Commission and little else.

The ink was scarcely dry on Kennedy’s bill when the city of Birmingham exploded in a tangle of firehoses, snarling police dogs and writhing Negroes. The violence was ugly, and so were the political implications. Soon afterward Kennedy announced that he was sending to Congress a much tougher version of his bill.

That bill, the skeleton on which the legislation presently before the Senate was fleshed, was submitted June 19, 1963. It called for: 1) a ban on discrimination in hotels, motels, restaurants and stores, and authorized the Justice Department to bring suit to force compliance; 2) power for the Attorney General to file desegregation suits against public schools and colleges; 3) withholding of funds from federally assisted programs where discrimination was practiced; 4) establishment of a Community Relations Service to help cities and towns over the rough phases of desegregation; 5) strengthening the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity by giving it a statutory basis.

The House Record. But even that package was not nearly strong enough for civil rights advocates in the House of Representatives. Brooklyn’s Democratic Representative Emanuel Celler and his tenman Judiciary subcommittee produced a bill that fairly bristled with teeth. Where Kennedy had asked for voting rights protection for federal elections only, the subcommittee bill included all state and local elections as well. In public accommodations, the Celler group measure added a ban on discrimination in any business that “operates under state or local authorization, permission or license.”

Both President Kennedy and Brother Bobby believed that this bill was too drastic to have a chance of legislative approval. In testimony before the full Judiciary Committee, also chaired by Celler, the Attorney General protested: “What I want is a bill, not an issue.” Celler was willing to compromise a little, but not much—and in his drive, he got some vital help from House Republican leaders. In conferences with Celler and President Kennedy, G.O.P. Floor Leader Charles Halleck and Ohio’s William McCulloch, the ranking minority member of the Judiciary Committee, pledged their support for a slightly watered-down version of the Celler package. They asked only one thing in return: that the President publicly acknowledge the G.O.P. contribution. Kennedy agreed.

That was last fall, just before the assassination. Lyndon Johnson took up where Kennedy had left off, gave Republicans full credit for their stand, and urged the House to pass the bill as a memorial to Kennedy. Halleck remained steadfast in his support, and in February the House approved the measure by a vote of 290 to 130. For the bill were 152 Democrats and 138 Republicans; against it were 96 Democrats and only 34 Republicans.

Critical Eye. Now it was up to the Senate—and even among Senators favoring civil rights there were some grave reservations. Everett Dirksen, for one, had been following the course of the House civil rights measure with a close and critical eye. Says he: “I kept annotating it and making a list of prospective amendments.” In early

February, just before the House passed the bill, Dirksen entered Washington’s Sibley Memorial Hospital for treatment of a bleeding ulcer, took along his own dog-eared copy of the measure and began to rewrite it. He kept at it during a week’s recuperation at Broad Run Farm, his redwood-and-field-stone ranch house in suburban Sterling, Va.

Discussing the period after the civil rights bill first reached the Senate, Dirksen recalls that “We sort of let the thing simmer and jell, waiting to see what would happen. We knew that we could expect a freshet of long speeches. We knew that for about 30 days nothing would happen.”

Help from Hubert. In the interim, Dirksen met almost daily with his top legal aides—three experts on constitutional rights and administrative procedure—and the four men picked the House bill apart. After weeks, they had accumulated a sheaf of some 70 amendments, many technical, some substantive. This was the em-ryonic Dirksen “substitute package.”

It was ready for unveiling in late April, and Dirksen explained it at meetings of the eleven-man Senate Republican Policy Committee. “I was trying,” he says, “to condition them a little as to what I had in mind for this bill.” There was some grousing, mostly from New Hampshire’s Norris Cotton, Iowa’s Bourke Hickenlooper and Kentucky’s Thruston Morton, who were upset over the bill’s equal-employment-opportunity section. To a certain extent, Dirksen agreed with them; his own Illinois has strong laws in this area, and Ev found that the bill might usurp states’ jurisdiction. His amendment took away the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s right to file suits.

By now Republican Dirksen and Democrat Hubert Humphrey were in almost constant touch. Early in the civil rights debate Humphrey knew that he had a hard core of 41 Democrats who could be relied on to vote for cloture.

Dirksen could count on only twelve to 14 Republicans. The total fell far short of the two-thirds vote that would be needed to shut off a filibuster. Slowly, carefully, patiently, Dirksen went to work on even more amendments, all calculated to bring more Republicans into the cloture fold.

By mid-May, recalls Dirksen, his amendment package was “in pretty tangible shape.” At Dirksen’s suggestion, Humphrey arranged for a bipartisan meeting between Senate and Administration leaders. The place: Dirksen’s leadership office with the tinkling chandelier that once belonged to Thomas Jefferson. The participants: Dirksen, Mansfield, Humphrey, California’s Republican Senator Tom Kuchel, Attorney General Kennedy, Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, and a sprinkling of liberals, moderates and conservatives from both parties.

In five conferences, agreement was finally reached on the package, essentially a rewritten version of the House bill. On May 26 it was introduced to the Senate by Dirksen as an amendment. Said he: “I doubt very much whether in my whole legislative lifetime any measure has received so much meticulous attention.”

The Thrust. The bill contains sections dealing with discrimination in voting, public accommodations, publicly owned facilities, education, employment, and federally assisted programs. It also extends the Civil Rights Commission, sets up a Community Relations Service and provides a variety of enforcement powers ranging from court injunctions to jail terms of six months and $1,000 fines (TIME, May 29).

In many ways, despite other Senators’ heavy involvements, it is Dirksen’s bill, bearing his handiwork more than anyone else’s. Dirksen’s 70-odd amendments are less notable for their number than for their thrust. In essence, he has changed the bill so as to allow the states more leeway in controlling their own civil rights conflicts, and to bar possibly overzealous federal officials—such as an Attorney General—from charging in and initiating civil rights suits without first establishing a “pattern” of discrimination. On both sides of the Senate aisle, almost everyone agrees that Dirksen’s proposed amendments vastly improved the House-passed bill.

Just what lay behind Dirksen’s endless efforts to shape a workable civil rights bill? Although he voted for lesser civil rights measures in 1957 and again in 1960, there is nothing in his background to suggest that he is any sort of civil rights crusader.

The Essence. To Ev Dirksen, the answer to that question is simple enough. “I come of immigrant German stock,” he says. “My mother stood on Ellis Island as a child of 17, with a tag around her neck directing that she be sent to Pekin, Illinois. Our family had opportunities in Illinois, and the essence of what we’re trying to do in the civil rights bill is to see that others have opportunities in this country.”

Last year Chicago Negroes, protesting that Dirksen had not committed himself on the civil rights bill, threw up a picket line around a hotel where Ev was scheduled to speak. Throughout his long political career—16 years in the House, 14 in the Senate—he has received little support from Negroes. He feels a certain bitterness about all this, but not enough to affect his advocacy of the civil rights bill. Explaining his support of that measure, Dirksen says: “I have looked at all the people who came into this office to see me—lawyers, contractors, businessmen, ministers, rabbis, priests. It was a constant walkin. And I thought: something must be done. Civil rights can’t and won’t be put off. Do we duck it or come to grips with it? Suppose we don’t do something? What will be around the corner in the way of national tranquillity?”

Even so, Dirksen was far from ready to accept what he thought was a bad bill—and the shouts of professional civil rights men bothered him hardly at all. “If the day ever comes,” he said, “when, under pressure or as a result of picketing or other devices, I shall be pushed from the rock where I must stand to render an independent judgment, my justification in public life will have come to an end.”

Thus Dirksen labored, and chipped, and carved, and chiseled toward what he considered to be a fair, realistic measure. For 87 days Democratic segregationists filibustered. But finally the hour for the cloture vote approached. On the morning of the big day, Dirksen arose at 5 a.m., half an hour earlier than usual, at Broad Run Farm. He joined his wife Louella in the kitchen for a breakfast of cereal and toast; then the pair went outside to Dirksen’s beloved rose garden, where he clipped some long-stemmed beauties to take to his office. Shortly after 8 o’clock, Dirksen’s chauffeur-driven Cadillac, a perquisite of his position as minority leader, came for him. Dirksen kissed Louella goodbye and, carrying his bulging briefcase and the fresh-cut pink roses, stepped into the car for the 32-mile ride to Capitol Hill. As he arrived in the Senate chamber, Last-Ditch Filibuster Robert Byrd, a West Virginia Democrat, was just sitting down after a 14-hour all-night speech.

Still, the Demonstrations. Even as the historic cloture vote was achieved, Negro demonstrations kept cropping out across the U.S. In St. Augustine, Fla., there were riots, and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was thrown into jail for trying to integrate a white restaurant. In Tuscaloosa, Ala., a pitched battle broke out between cops and 500 Negro demonstrators. In Canton, Miss., bombs were hurled at a Negro home and church.

All this went to prove a vital point. Many whites, resentful of the Negro revolution, think of the civil rights bill as an incursion into their own rights. It isn’t. At the same time, many Negroes believe that the bill will end all their troubles, that upon its signing they will enter a bright new era that is free from prejudice. They are wrong too. Civil rights conflicts will continue this summer and next summer and for summers stretching far into the future.

What the civil rights bill will do is provide a broader legal basis for the equality of opportunity. That is all it is meant to do, and certainly that is plenty. Ev Dirksen knows it well. With a good deal of Democratic cooperation, he practically wrote the thing.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com