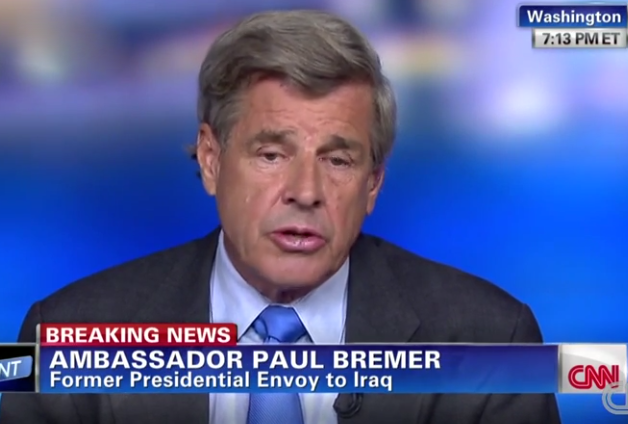

L. Paul Bremer, who ran Iraq in 2003 and 2004 as President Bush’s envoy, is suggesting what the U.S. should do there on the Wall Street Journal’s op-ed page and CNN. John Bolton, Bush’s U.N. ambassador, is doing the same on Fox. Paul Wolfowitz, the Pentagon’s No. 2 civilian at the time, is offering his counsel on NBC, MSNBC and CNN. These are Bush Administration officials who led us into Iraq in 2003 and fumbled what followed. Their comrades in launching that war from outside the Administration are also arguing for a more muscular U.S. foreign policy and action in Iraq.

Only in Washington are such second acts in American life possible. As Iraq began falling apart faster than normal last week, reporters and television bookers rushed to interview those involved in the original Iraq invasion. “The Vulcans” was the nickname for the team of Bush foreign policy advisers that helped get him into the White House, and then got the nation into Iraq. In many ways — building the case for war on nonexistent weapons of mass destruction, linking Iraq to the 9/11 attacks, lowballing the war’s cost and duration — they weren’t just off, but were completely wrong.

So why are the Vulcans coming home to roost now? More important, should we be listening to them for guidance on what to do?

James Mann is author of the highly regarded Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush’s War Cabinet. “It’s natural that we would like to hear from them with Iraq in the mess it is in today,” says the former veteran national-security reporter for the Los Angeles Times. “To hear not so much, ‘Well, gee, what do we do now?’ but the obvious questions about ‘What went wrong?’”

He finds it strange that Bremer and others seem eager to focus on Iraq’s future, rather than what they did that contributed to the current crisis. “In general, they’re just not the people I would ask, ‘What do we do now?’” Mann says. “I thought it was odd to be listening to Bremer’s advice on this. He’s the guy who disbanded the [Iraqi] army, and that single action probably had the greatest causative effect to the mess we see now of anyone.”

Mann argues that he doesn’t want to “ban” Bush Administration officials from talking about Iraq, but thinks journalistic questioners should focus on their past actions and not their future recommendations. That’s why he prefers to see them in a televised Q&A format where they can be asked about what happened, rather than simply writing a column suggesting marching orders for the U.S. military. “I think I’ll stay out of whether the Journal should have published” Bremer’s op-ed on Monday, Mann says.

Andrew Bacevich, a retired Army colonel now teaching international relations at Boston University, thinks the recycled views of Bush Administration officials and their allies (here and here, for example), fit into a U.S. foreign policy narrative dating back to 1938, when Europe’s major powers refused to stand up to Adolf Hitler. “Their view of history, to my mind, is badly distorted if not simply false, but it is a view of history to which they are devoted,” he says (Bacevich takes them on here). “If you want to summarize that history in one word, it would be Munich.”

The Munich mind-set demands that the U.S. be perpetually forward-leaning when it comes to confronting evildoers, and primed to attack if the evildoers don’t back down. “In the immediate wake of Iraq, to come back now and say ‘Listen to me as I prescribe a recommitment of U.S. forces to Iraq’ as somehow a way to fix the problem, they cannot grasp how foolish they sound because of their distorted view of history,” Bacevich says.

Some foreign policy experts, like Bacevich, are noninterventionists because they view the world through the prism of a different war. “Our worldview tends to derive from the experience of Vietnam in any sort of circumstance in which there is an argument about whether or not it’s appropriate to employ military forces,” he says. “There’s going to be people in my camp who say, ‘Nay, nay, nay — if we involve ourselves we’re going to replicate the Vietnam war.’”

People in both camps tend to be products of the coasts and elite universities, Bacevich says. They don’t generally come from the nation’s heartland — “somewhere between Iowa and Indiana,” in his words — and include “very few people who graduated from Big 10 universities.”

U.S. national-security strategy would make far more sense if its blacksmiths didn’t bring such worldviews into the Oval Office when the nation is weighing the use of force. “One of the things that so cripples our foreign policy discourse is our collective inability to free ourselves from whatever version of the theology we happen to subscribe to,” Bacevich says, “and really see the world as it is.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com