The E3 2014 demo for Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain was unexpectedly hilarious. Before it was over, a horse had realistically defecated. A large cardboard box had waddled from spot to spot in plain view of enemy soldiers. An e-cigar that emitted holographic smoke became a trippy time machine. And limp bodies, vehicles and at one point even a tranquilized sheep flew through the air, attached to makeshift helium balloons. The series’ playful and often strange sense of humor is alive and well in The Phantom Pain.

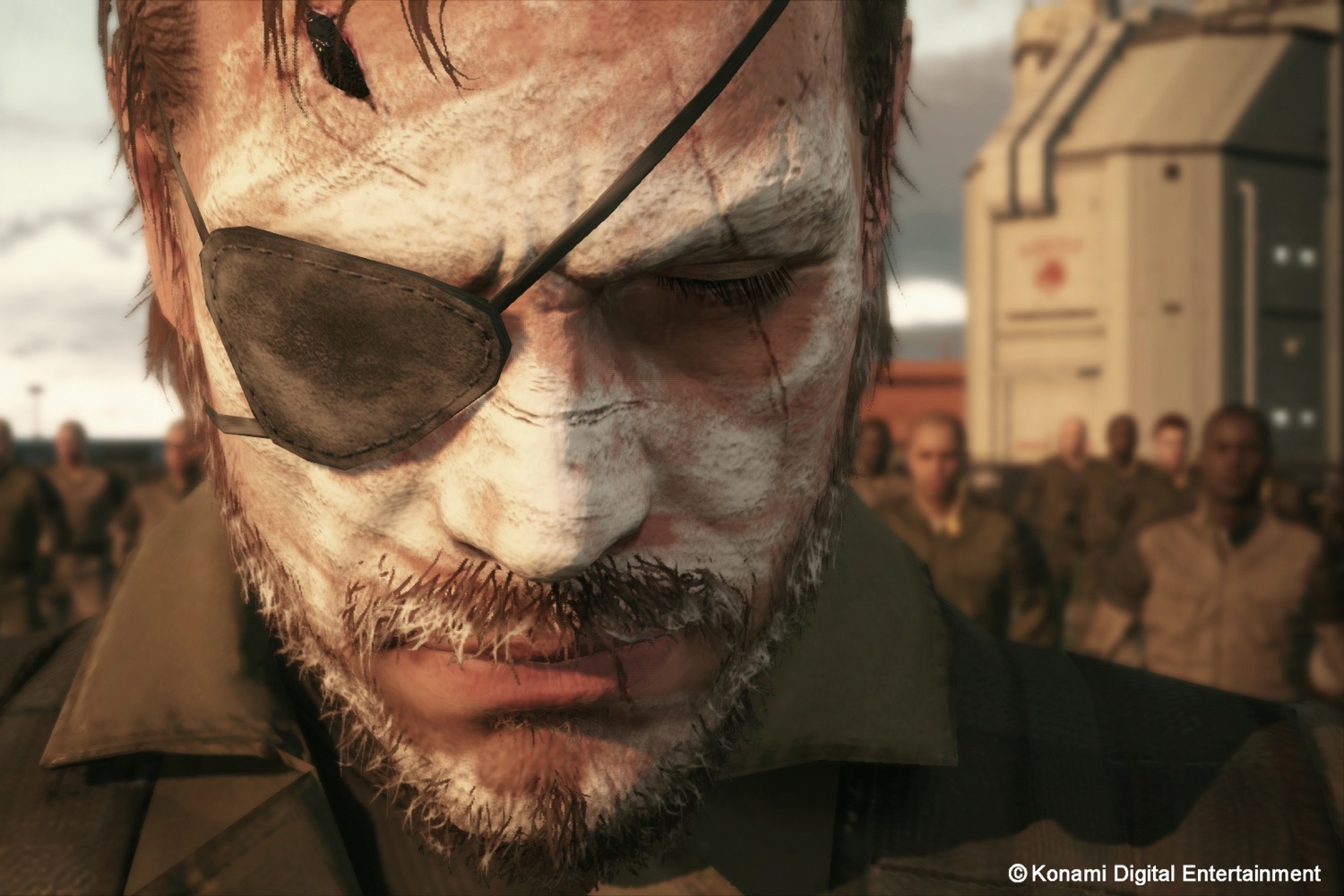

But more often, the demo, which takes place in Afghanistan nine years after the events in Ground Zeroes, played up the idea that The Phantom Pain is going to be as visually arresting, tactically sophisticated and vast as its celebrated creator Hideo Kojima claims — as far removed from the original PlayStation game released in 1998 as a film like Raiders of the Lost Ark from Casablanca.

The demo also revealed a few things we hadn’t seen yet. The series’ cardboard box you can wear like camouflage is back with a few new tricks: You can pop out of its upturned bottom to surprise enemies, or quickly abandon it by cannonballing forward to evade suspicious guards. Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker‘s “Fulton surface-to-air recovery system” that let you deploy harness-attached helium balloons to dispatch objects skyward is also returning, allowing you to send enemies, allies you’ve rescued, poor wandering animals and even stuff as improbable as shipping containers and military SUVs zipping through the sky back to your Mother Base.

The Mother Base — your ocean-anchored headquarters in the game — can be custom-tailored section by section and benefits from all the content you manage to secure with the Fulton system. That content includes natural resources you’ll have to glean through careful scouting, and which you can sell to supplement your income.

When you’re infiltrating enemy compounds from any number of vantages — the crux of the series’ new spatially open-ended selling point — you’ll find enemies keeping routines that correspond to full day and night cycles. If you don’t want to wait in real time for guards to shift to positions that favor your tactical approach, something called an e-cigar (or “phantom cigar”) that emits holographic smoke lets you speed up time. And weather now happens dynamically and purposefully: At one point a sandstorm blew in thick enough to blot out everything onscreen, shutting down your ability to spy and radar-tag enemies (though, as well, their ability to see you).

In all, the demo impressed as it was intended to, confirming that all the classic Metal Gear DNA lives on, stitched into an open world that requires you take the time to scout an area from multiple angles and observe enemy patterns, set your own approach vectors and establish reliable exit points instead of being walked through restrictive scenarios corridor by corridor.

I caught up with Mr. Kojima at E3 2014 to ask him about the game (at this point it still has no release timeframe) as well as his plans for the series down the line. Here’s what he told me.

The Metal Gear Solid games explore politically complex and occasionally controversial themes, in particular the questions of ends and means as relates to war. To what extent are we seeing your own political views filtering through these narratives?

It’s not only about my political views, but I really like movies. I try to watch a movie a day, if not more, and through movies I learned about so many different political themes I hadn’t been interested in and cultural things I hadn’t been aware of and economic factors I hadn’t thought about. So I think that entertainment goes beyond this.

In the case of films, you can sit down for two hours and have a good laugh and say “Oh god, that was funny.” But for me at least, my experience with movies has gone beyond that. It’s brought to me things I wasn’t interested in or aware of.

Now I don’t think you see many games that have this same message, one that goes beyond just being an entertainment medium. I think that’s part of my role, part of my duty, to put in my games what I experience through movies, to explore this philosophy that movies gave me. I want to provide something similar to people through the games I create.

The games also seem to have this interesting contrast between a general anti-violence or antiwar message — this notion that you’re trying, in whatever limited way, to save the world from itself — and the sort of physical violence you yourself perpetrate as you play.

Metal Gear Solid is for the most part an infiltration game. You go somewhere, you execute your mission, then you go back. Those are your actions as the player. You choose what to do — things that question your morality and your values.

In the case of a movie, in the end it’s a different character separate from you executing all these actions. But in the game, it depends on you. It depends on your will to execute, to do something, to be violent or not. So I do try to portray this. I feel like this is something unique, that I can portray this violence, and then the user can experience the truth of what that kind of violence entails, what elements people should have in their mind. So yes, it’s a kind of contradictory approach, but I want people to understand the side effects, the effects of violence through experiencing battles in the games.

For example, the Metal Gear games have always had an anti-nuclear message. So in Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker [the game Metal Gear Solid V follows chronologically] I tried to question why countries get nuclear weapons. In Peace Walker, there’s Costa Rica, a country without an army. The player creates an army to protect the country, starts developing soldiers, starts developing an army and with the rise of this third power in the world, the rest of the world tries to attack and get rid of that power. The player is thus placed in a situation where they can choose to acquire a nuclear weapon that’s been seen up to that point as completely wrong and bad. The player is given that choice. So at that point, the player is put in a position where they’re having to weigh this concept of nuclear deterrence and avoiding war by having nuclear weapons and whether that’s something good or bad is completely up to them.

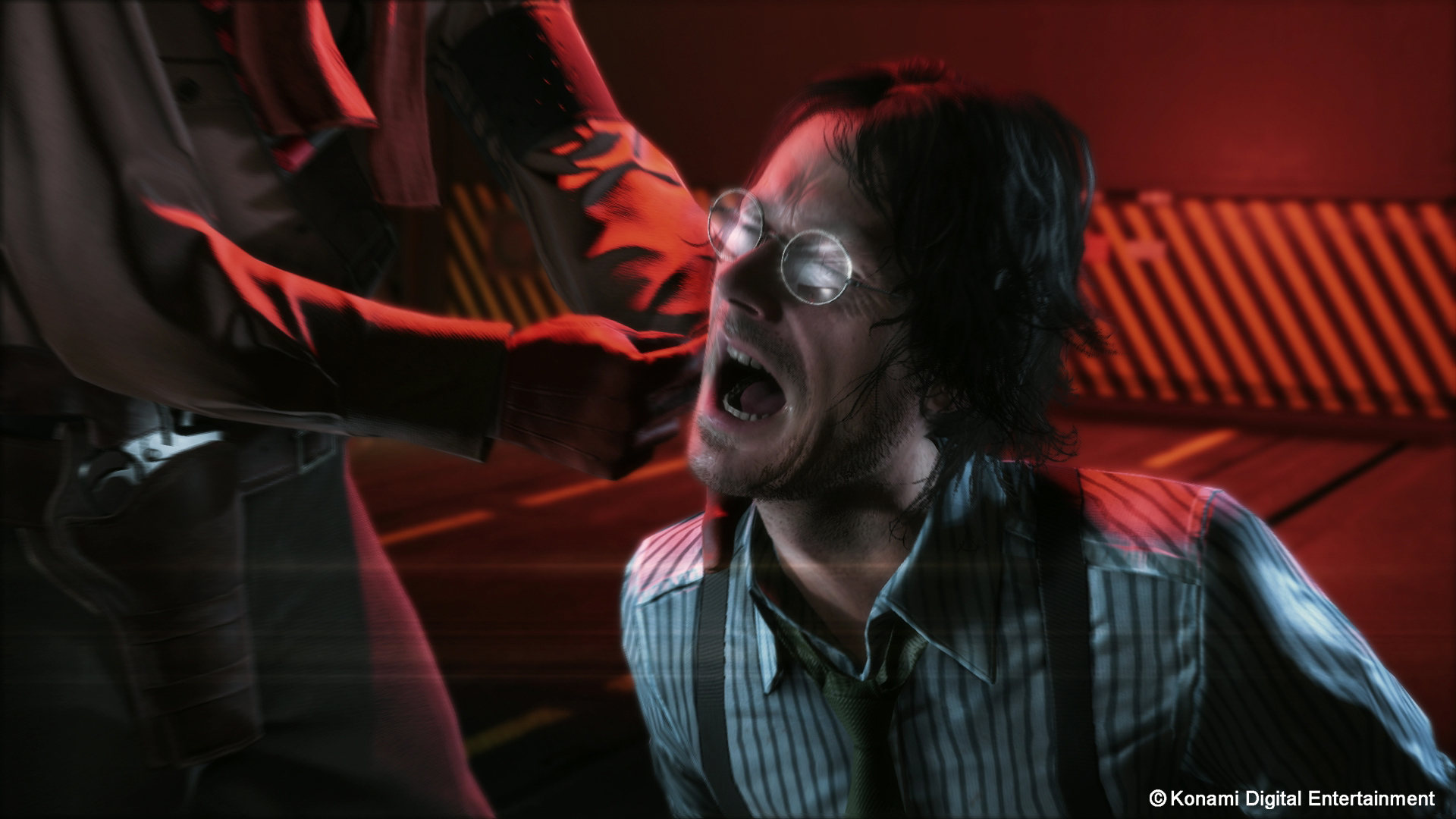

In the older Metal Gear games, the violence was abstract because the visual technology was so much cruder. In Metal Gear Solid V, the engine’s now realistic enough that I’m wondering how you walk the line between realism and gratuitousness.

I’m not sure this will completely answer your question, but it’s not about the engine, it’s not about the graphical fidelity, because I’m not trying to portray violence. I’m trying to portray what is violence itself. So the relationship with the graphics isn’t too strong, I’m just trying to pose the question to the player through an interactive medium, “What is violence?”

There are so many games where you fight aliens or zombies, and they have very high-fidelity graphics, but they don’t ask the question of why the events are happening. In Metal Gear, I’m trying to get at why all these violent things happened in the first place. My intention is to get the player to question why these things are happening.

On the flip side, the Metal Gear Solid games have this quirky sense of humor, like the realistically defecating horse in the demo or the knocked-out flying animals. Where does that come from?

My games are rather stressful games, where you have to play for a long time. When you have to infiltrate you have this constant stress of “When am I going to be spotted?” So there’s this constant tension. And this is something similar to what Alfred Hitchcock did in his movies. They were just too serious and too heavy for one person, to go through the movie for hours. So what he did, in order to relieve that tension and stress, was to add humorous elements. I’m doing something similar in my games.

I know that no one would ever wear a box in war, but I want to change the mood, relieve the stress and tension and control a little bit the feelings of the player by letting them calm down and relax for a second and then continue through the mission. Placing this stuff through the game strategically, I think that it helps the player stay in the game for longer periods of time, and helps me tell the very serious story I’m trying to relate.

After Metal Gear Solid 4, you said you were leaving the Metal Gear Solid series, and yet here you are, working on not just one but two games — one released, one still to come — that comprise the fifth installment. Why come back to it again?

Originally I wanted to hand the series off to younger staff and let them carry on with it. And so we did, and that resulted in the game Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance. But after Rising, we found that for my younger staff, the numbered games were just too heavy for them. So that’s why I decided to come back and work on them myself. Ideally I’d want them to handle this, and for myself to be focused on creating a different IP. That said, Metal Gear is a huge title, it usually has a massive budget, and that wouldn’t happen for any game.

So in a way I guess I’m taking advantage of that to try new things, because every time I work on any game, be it Metal Gear or something else, I try to make new things. So for me, my challenge right now working on Metal Gear is, while preserving the elements that make it Metal Gear, to do all the new things I really want to do.

And this time — I’ll say it again — this is the last one. Not the last Metal Gear, but the last one I’ll work on. This is my focus when I go into working on a game. Every game I make, I create thinking it’s really, really going to be the last game I create. So I put as much as I can in and make sure I have no regrets.

What about gaming hasn’t changed over the past few decades?

I think that obviously the technology has evolved a lot, from sound to graphics to gameplay. And the content of the game, what is really the essence of the game, hasn’t moved much beyond Space Invaders. It’s the same old thing, that the bad guy comes and without further ado the player has to defeat him. The content hasn’t changed — it’s kind of a void.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com