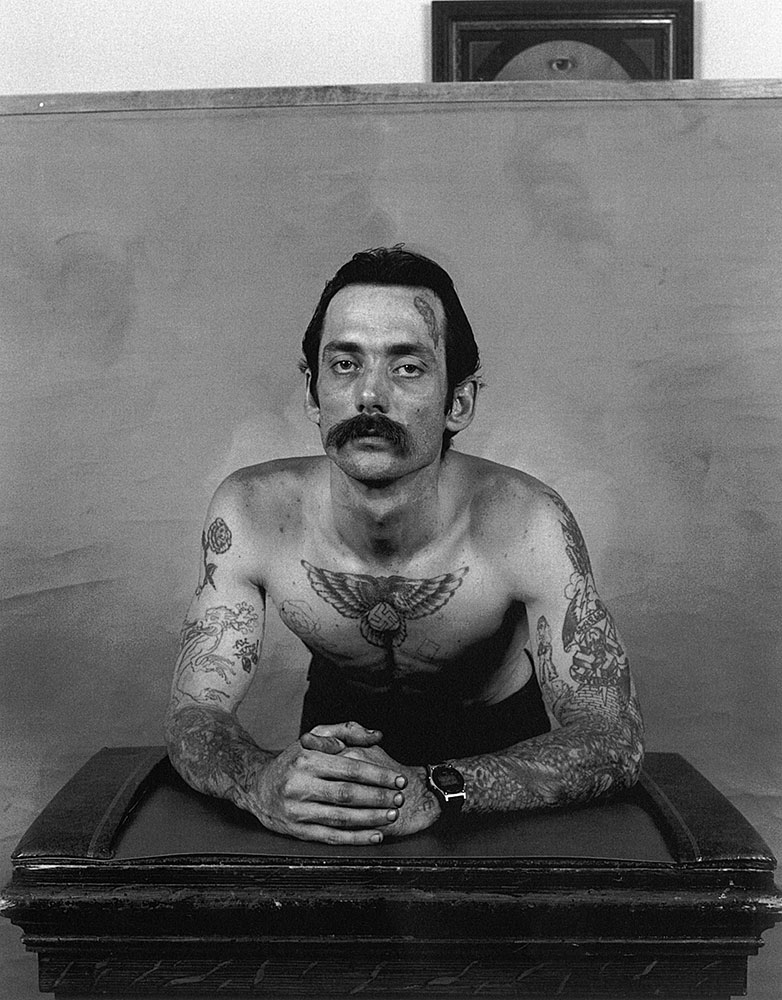

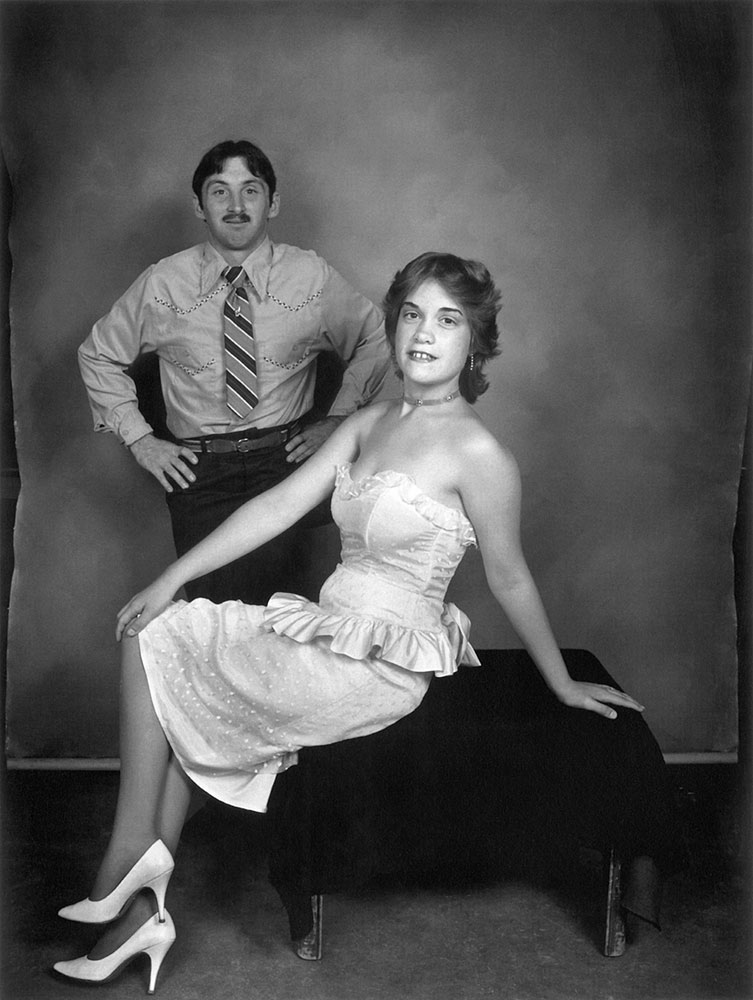

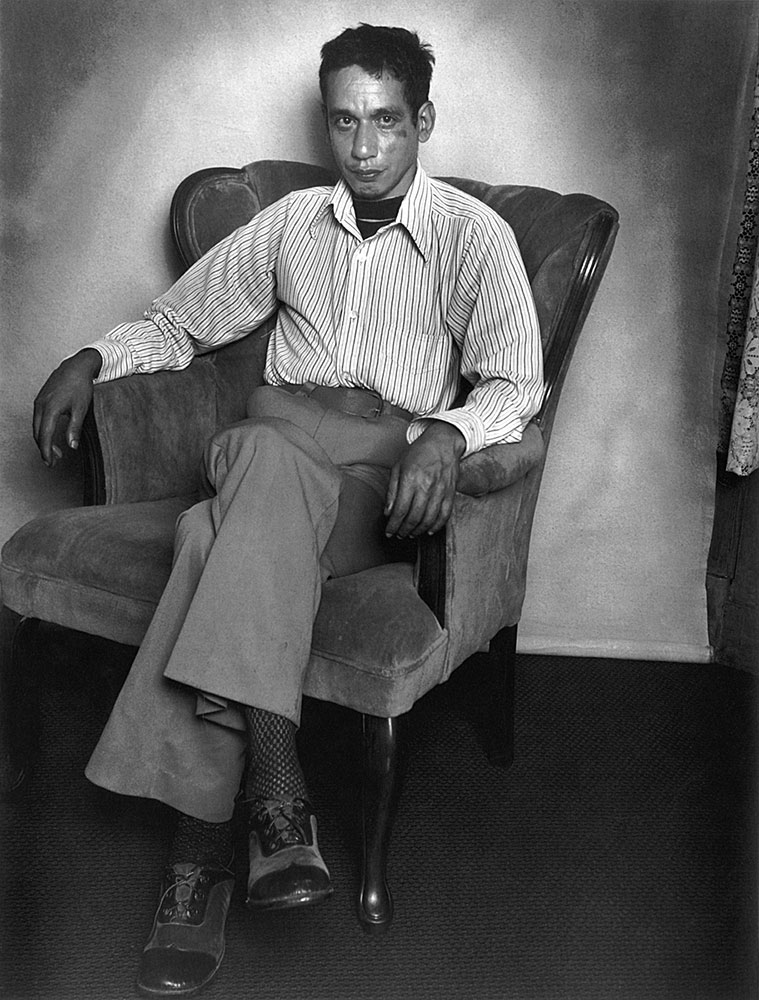

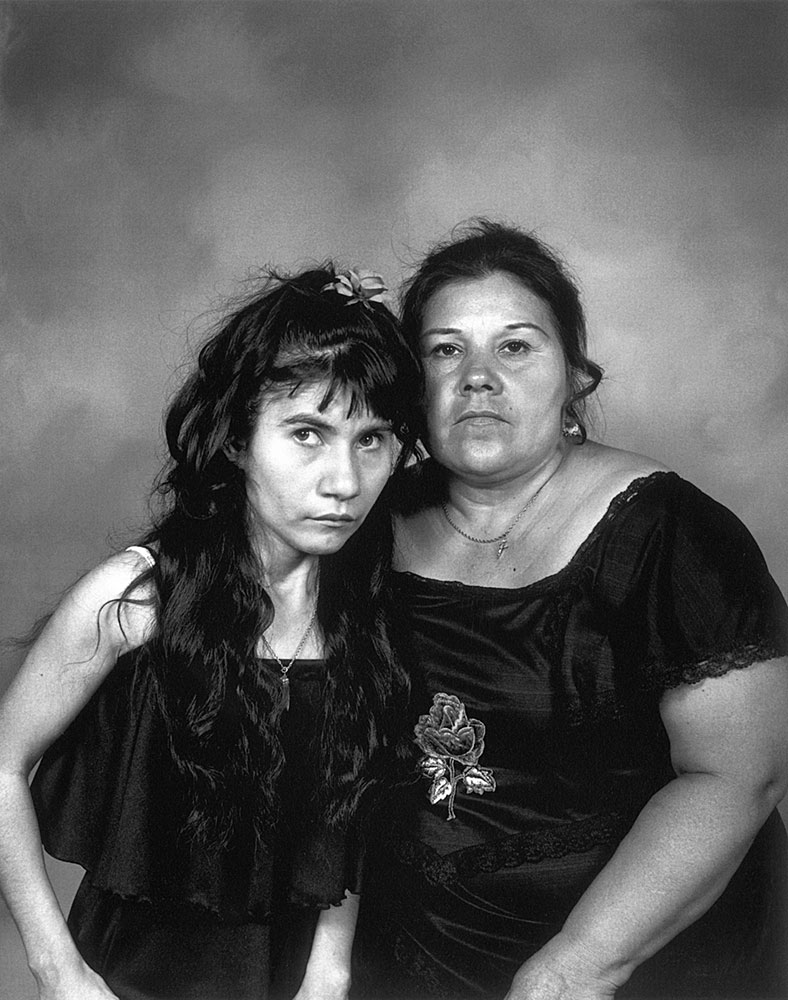

More often than not, some of the best observers of places are those not originally from there. Leon Borensztein was born in Poland, settled in Israel and emigrated only later in life to the U.S. in 1977. But unlike de Tocqueville and other aristocratic travelers of old, he had to make ends meet and stumbled into taking commercial pictures of average, normal Americans as a fly-by-night job to pay the bills. Borensztein’s portraits—comprised in his new book, American Portraits, 1979–1989, published this month by Nazraeli Press—took place on the sidelines of commercial gigs. His tools and techniques were dictated by his means: a generic backdrop, a camera, simple and spare.

Yet the depth and quality of Borensztein’s oeuvre place him in a storied canon of chroniclers of America, stretching past those intrepid visionaries of the Farm Security Administration, photographers who voyaged out into a country blighted by the Depression and returned with snapshots of its soul — weary, defiant, beautiful. Early portrait photography — be it conducted by socialist sympathizers during the New Deal or the ethnographic work of turn-of-the-century imperialists — all sought after a kind of authenticity. Gone was the age of outsized oil-canvas monarchs. Now was the time of the quotidian and real, a moment imbued not only with a sense of place, but of human feeling.

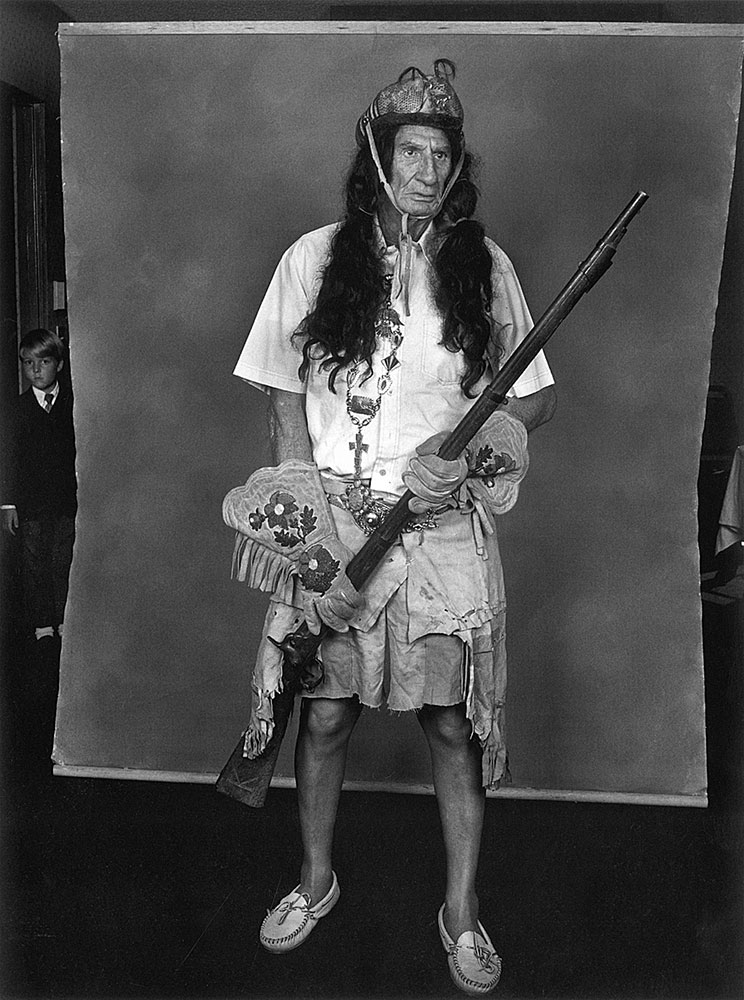

Borensztein brings this tradition to bear in his work, but does not belabor it. There is, after all, as the first picture above of the man in Native American headdress makes plainly clear, an artifice involved. He shot modest homes, inhabited by unassuming people. He instructed his subjects specifically not to smile, a marked contrast from the faux-mirth and conviviality of his commercial work, which often relied on the same subjects. Reflecting on what the portraits represented, Borensztein once suggested his “black and white images reflect the alienation so typical of today’s America.”

But even a brief sampling of his pictures would communicate far more to the viewer. They are at once hemmed with a wry, sardonic edge, yet brim over with Borensztein’s genuine empathy for his subjects. Still, “they are not sentimental,” writes Sandra S. Philips, a curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Borensztein gives us a world of feeling with a light, almost imperceptible touch. The subjects radiate loneliness and coziness, an empty despair and a glowing hope for the future. Gazing at Borensztein, the man with the camera and that background, “they partly represent him,” writes Philips. “They partake of his curiosity, amazement and tenderness when he looked at these American people.”

Leon Borensztein’s book American Portraits, 1979–1989, was published this month by Nazraeli Press.

Ishaan Tharoor is a writer-reporter for TIME and editor of Global Spin. Find him on Twitter at @ishaantharoor.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com