Sucrose, glucose, fructose, maltose, dextrose—can you tell the difference? Probably not, even if you’re a careful reader of food labels. Unlike fats, which are broken down on nutritional labels as saturated, trans, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated, sugars are listed as “sugar.” If you read the full ingredient list you may find clues as to what kind of sweetener is in there, such as high fructose corn syrup or dextrose or maltose. But when it comes to figuring out exactly how much of each is there, you’re on your own.

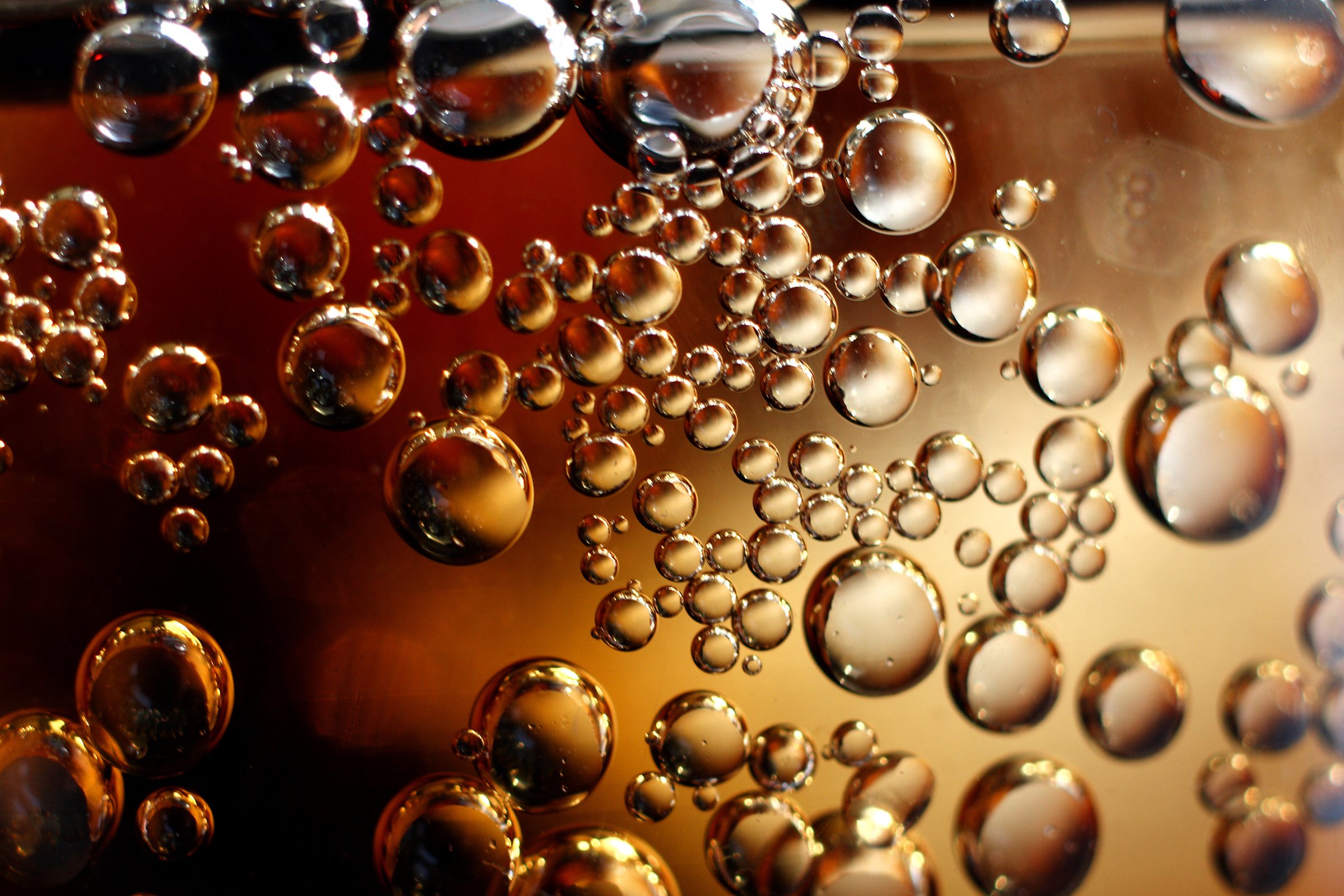

Michael Goran, professor of preventive medicine and the director of the childhood obesity center at the Keck School of Medicine of University of Southern California, analyzed popular sodas and found that they contained more fructose—a form of sugar that essentially behaves like fat in the body and has been linked to obesity and type 2 diabetes—than their labels suggest. In Goran’s analysis, Dr. Pepper, Pepsi, Sprite, Mountain Dew, Coca-Cola, Arizona Iced Tea and 7-Up contained more than 58% fructose. These results were consistent across three different ways of analyzing their chemical makeup. “What was surprising was the consistency across the methods and the consistency across beverages,” he says. “We saw a consistent ratio of fructose to glucose of 60-40.”

He also found that some drinks that don’t list fructose as an ingredient also contained detectable amounts of the sweet stuff. Pepsi Throwback and Sierra Mist, which do not list HFCS as an ingredient, still contained 37% and 7% of fructose, respectively. Mexican Coca-Cola, which lists only sucrose, also showed higher concentrations of fructose than glucose; sucrose, even if it’s broken down, should lead to equal contributions from both. “If fructose is damaging, then we need to know how much fructose is in our food and beverages,” says Goran.

MORE: 7 Not-So-Sweet Lessons About Sugar

There’s a lot that scientists still don’t know about how the various forms of sugar work in the body, but here’s what they do know. Sucrose, or table sugar, is made up of two carbohydrate molecules paired together: glucose and fructose. Once in the body, the couple splits up and goes two very separate ways. Glucose is the body’s main form of energy, so those molecules are immediately used by cells or stored as fuel for later.

Fructose, on the other hand, can only be processed by the liver, where it behaves like fat. High fructose corn syrup (HFCS), a staple of processed foods and drinks, is glucose that is treated with enzymes so it produces various proportions of fructose; the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allows for HFCS42 and HFCS55, which contain 42% and 55% fructose, respectively, with the remainder made up of other sugars, primarily glucose.

MORE: 12 Breakfast Cereals That Are More Than 50% Sugar

Why does all this matter? Since fructose isn’t used by the body for energy, it simply contributes to weight gain and diabetes—not exactly a desired effect. Dr. Robert Lustig, a professor of pediatrics in the division of endocrinology at University of California San Francisco, admits that there aren’t any studies showing how higher ratios of fructose greater than 50% may influence health. Still, that doesn’t mean that people should continue to be in the dark about how much fructose they’re consuming. Fats are more clearly labeled, and since research links trans fats to unhealthy outcomes, people can now see on labels how much trans fat foods contain. Likewise, he says, sugars should be broken down into fructose and glucose, so consumers have a better sense of how much of those sugars can potentially be burned off as energy, and how much will turn immediately into fat.

In response to TIME’s questions about the report, PepsiCo referred us to the International Society of Beverage Technologists (ISBT), a technical group of beverage industry professionals, which happened to publish a report on their own analysis of the fructose content of sweetened beverages on the same day. Not surprisingly, in their analysis of the same drinks, the results were very different. HFCS content in their analysis was right around 55%.

MORE: This Is What Happens When You Give Up Sugar for One Year

So who’s right? Larry Hobbs, co-author of the ISBT study, says that the method Goran and his team used is more appropriate for assessing honey, and not HFCS. Bela Buslig, a former research scientist with the Florida department of citrus who was not involved in either study, says that isn’t necessarily true—and that Goran’s methods were suitable to determine actual fructose content in these drinks. The fact that Goran’s group consistently found 60-40 ratios of fructose to glucose using three different analytical methods, Buslig says, suggests that the results are reliable.

MORE: WHO: Only 5% of Your Daily Calories Should Come From Sugar

Still confused? Until the FDA and the U.S. Department of Agriculture start mandating labeling requirements for sugar as they do for fats, you might stay that way. “My advice to consumers is to reject anything with HFCS,” says Goran. “That would be the first line of defense.” And as Marion Nestle, professor of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University adds, “The bottom line: everyone would be healthier eating less sugars of any kind.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com