The Department of Veterans Affairs is facing an emergency. Deception in record keeping, manipulation of data, lies to families, secret lists, systemic corruption at health centers. Yet this crisis of credibility is more than a short-term emergency at the department that pledges to fulfill Lincoln’s promise to “care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan.” There’s also a long-term challenge. To meet it, the VA leadership will have to move boldly to address questions both strategic and cultural.

I’ve worked with thousands of veterans since returning from Iraq in 2007. My team has honored nurses and doctors in the VA who saved lives, and there are many stories of the sweat and courage of VA employees that are too infrequently told. Many veterans are satisfied with the care they receive, and the VA has model programs for some illnesses. Yet almost every veteran has at least one story of VA dysfunction. Too much VA heroism is about fighting the VA itself by going above, under or around its beastly bureaucracy.

After the Pentagon, the VA is the single largest department of the government, spending more than $160 billion dollars a year and employing 300,000 people. Leading any organization of this size through a crisis would be difficult. At the VA, new leadership will have to build a team, shape a culture and develop a strategy to face the twin challenges of restoring credibility while also leading transformation.

At the moment, the VA is facing a crisis of demand. Veterans who need care can’t get it from VA hospitals. Because of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, many people believe that the veteran population is growing. It would be easy to think that the answer is simple: hire more and spend more. But in fact, we’ve lost more than 6 million veterans over the last 30 years, and veterans now represent less than 7% of the population. We face a future with millions fewer veterans in a country with millions more people. Over the long term, the VA will have to adjust to a shrinking population with changing needs. The right kind of planning will rely less on predicting the future and more on building a flexible system that responds quickly to shifting needs.

The current structure of VA healthcare makes that kind of planning difficult. A patient-centered approach would incorporate lessons from other hospital systems to create structures for physicians and hospitals to deliver excellence while providing flexibility for patients to go wherever they can to get the best care. This is easy to write and hard to do. But it’s the kind of thinking and planning that the VA must do if they are going to preserve centers of excellence and avoid the waste of half-filled hospitals and ghost town clinics. Solving this challenge will require close work with Congress on a sensible plan for consolidation in some areas, while expanding excellent care options for all veterans, especially those living in rural and remote areas.

Unlike the military, almost every function performed by the VA (healthcare, home loans, scholarships, cemeteries) has a clear private sector counterpart. Innovative leaders have to look to public/private partnerships and market competition and ask, “What works best?” We should rethink what services we want the VA only to pay for, and which ones we want it to provide.

In addition, through increased collaboration the VA can take far greater advantage of the work of high-performing non-profit organizations that are providing quality services to veterans. Perhaps more than at any time in American history, the average citizen is ready and willing to help veterans. But for reasons of privacy, health, and quality, the VA has built a high wall around its patients. (Some of these walls are necessary; there are many people with good intentions who create no results, and the field of those who say they want to help veterans includes people who are fraudulent and manipulative.) The VA should create a certification system for quality, proven organizations to make a difference in the lives of veterans who would benefit from the healing presence and helpful service of their fellow Americans.

In a similar vein, civil service reform may not seem exciting, but it’s essential. With 300,000 employees and a crisis of accountability, the VA must find ways to remove poor performers, promote and reward excellence and attract and retain top talent. Insisting on excellence is the best way to preserve, promote and celebrate the public service ethic shared by many VA physicians who forego higher salaries to serve veterans. Done right, reform at the VA could point the way toward a more dynamic and effective civil service.

Finally, any discussion of the structural and strategic challenges facing the VA has to include technology. Both the inability of the Pentagon and the VA to smoothly transition a service members’ health records and the VA backlog of disability claims have been well documented and much discussed. But without a fix, serious problems will persist.

In addition to these structural issues, there are cultural issues that must be tackled as well. Thus far, the VA has failed to fully integrate this generation of veterans into its systems or culture. Combat-injured veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan with pressing needs too often continue to wait in horrific lines. Their signature injuries—traumatic brain injury and PTSD–have still not been effectively addressed. And despite some women’s health centers, the VA too often thinks of veterans only as men, when female service members now make up 14% of the force.

The “pop a pill” approach to pain in general and to PTSD in particular is also hurting. There’s a place for prescription medication for some patients, but the side effects of overmedication too often include addiction and suicide. Exercise, service in the community, work with dignity, and meaningful relationships all seem to have a lasting effect on relieving PTSD. These are not things that a government can provide for its citizens; all people, veterans included, must be partners in the protection and promotion of their own health. The VA needs to encourage therapeutic plans that reinforce a culture of responsibility.

The disability system itself has also devolved into a cumbersome check-writing scheme unattached from commonsense understanding of disability. (Because of that, I and many others make a point of donating “disability” checks to charity.) Veterans who were disabled by war and need financial assistance to lead a dignified life should get it. Veterans who do not need disability payments should be able to easily opt out of receiving them, while not forfeiting their future eligibility should they suffer a setback. Lost eyesight rarely returns and limbs don’t grow back, but where a disability can be overcome, veterans should be aided by a system that incentivizes progress toward health rather than simply paying for disability. The money we save could be redirected toward programs that help reintroduce veterans as contributing citizens to society.

Many people who work with veterans are frustrated by media stories that focus on “troubled” veterans: stories of suicide, sexual assault, homelessness and crime. But the journalists who cover these issues are often veterans themselves, and many spent time embedded in military units. When they draw attention to flaws at the VA, they should be thanked rather than shut out.

Criticism of the media counts for little if veterans don’t join the conversation. Perhaps more than anything, new leadership at the VA must help the public to know the men and women I know: men and women who served with courage overseas and who’ve come back home to help us build stronger communities. The leader of the VA serves as the most visible and powerful spokesperson for veterans in the country. As such, he or she must help the country understand not only what veterans deserve, but also what they offer.

Many of these problems have roots that go back more than 50 years. They won’t be solved in five months. Still, discussions about veterans have been buoyed for too long by the rhetoric of intentions. We know that everyone wants to do well by veterans, but there is a vast difference between wanting a result and creating one.

The veterans that came home from World War II shaped a nation. The generation that came home from Vietnam shaped a culture. What will be the legacy of this generation? The men and women I served with were never afraid to do hard things. This too will be hard. But it’s what we all want: veterans, honorable employees inside the VA, and every American who believes it’s time we got this right.

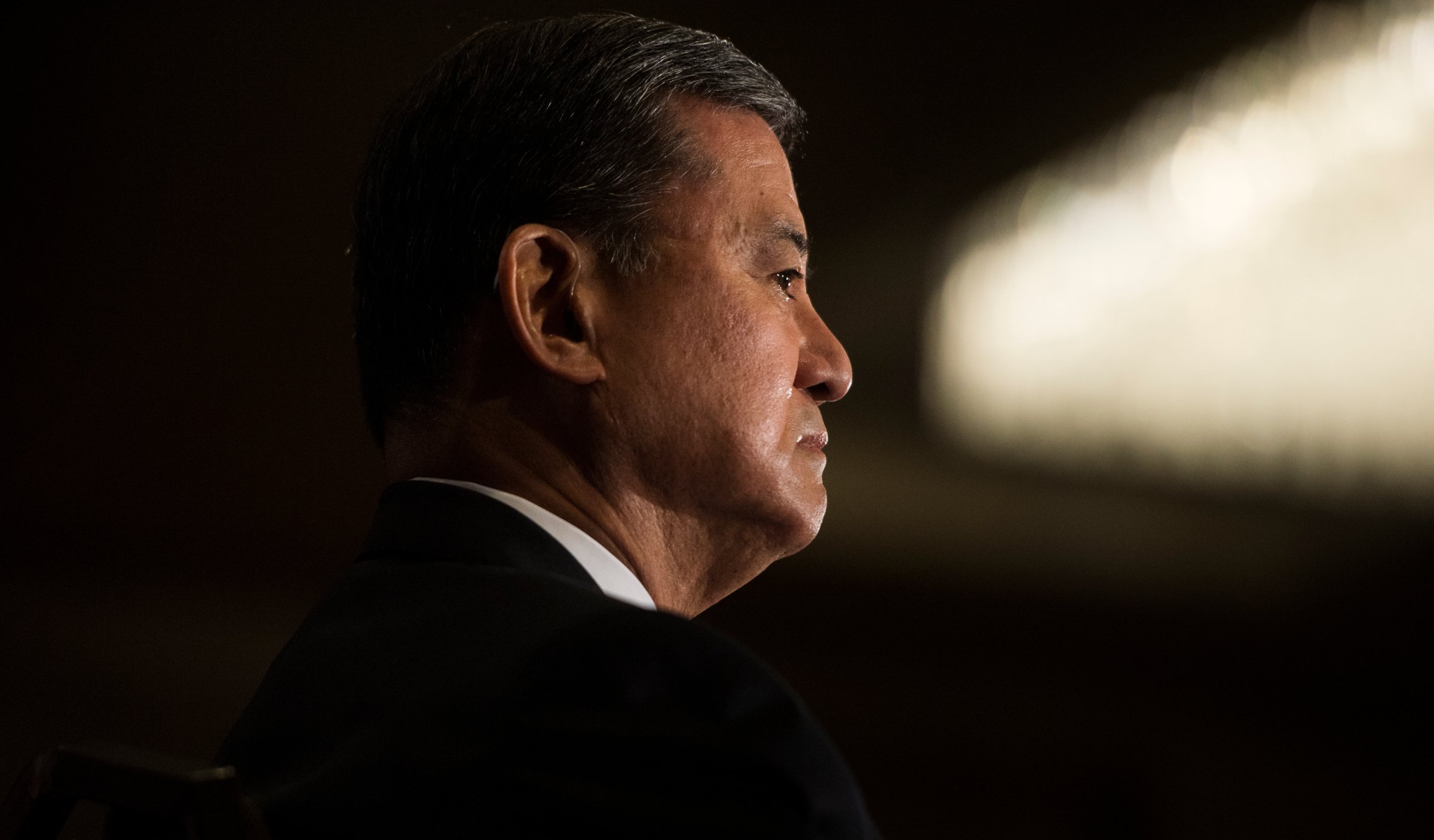

Eric Greitens, a Navy SEAL and founder and CEO of The Mission Continues, was a TIME 100 honoree in 2013. He was recently named by Fortune Magazine as one of the 50 Best Leaders in the World.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com