There is a wonderful scene in the popular 1980s movie Back to the Future. The film’s plotline sends a teenager raised in the heart of the Reagan era back to the ’50s. There, Michael J. Fox’s character meets the younger version of the mad scientist, Dr. Emmett Brown, who built the time machine that transported him. To check Fox’s bona fides, the scientist tests him.

“Then tell me, future boy, who’s president of the United States in 1985?”

“Ronald Reagan,” Fox answers.

“Ronald Reagan? The actor?” Christopher Lloyd’s character laughs incredulously. “Then who’s vice president? Jerry Lewis?”

All these years later, the joke continues to be on Ronald Reagan’s skeptics and doubters. The man whose political skills were mocked by California’s legendary governor Pat Brown and then by all the smart guys in the Carter White House made believers of those political rivals by rolling up historic electoral landslides in California and then the nation. Twenty-five years after he flew west on Air Force One for the last time, it is safe to say that millions of Americans would still love to go back to the future and have President Reagan in the Oval Office once again.

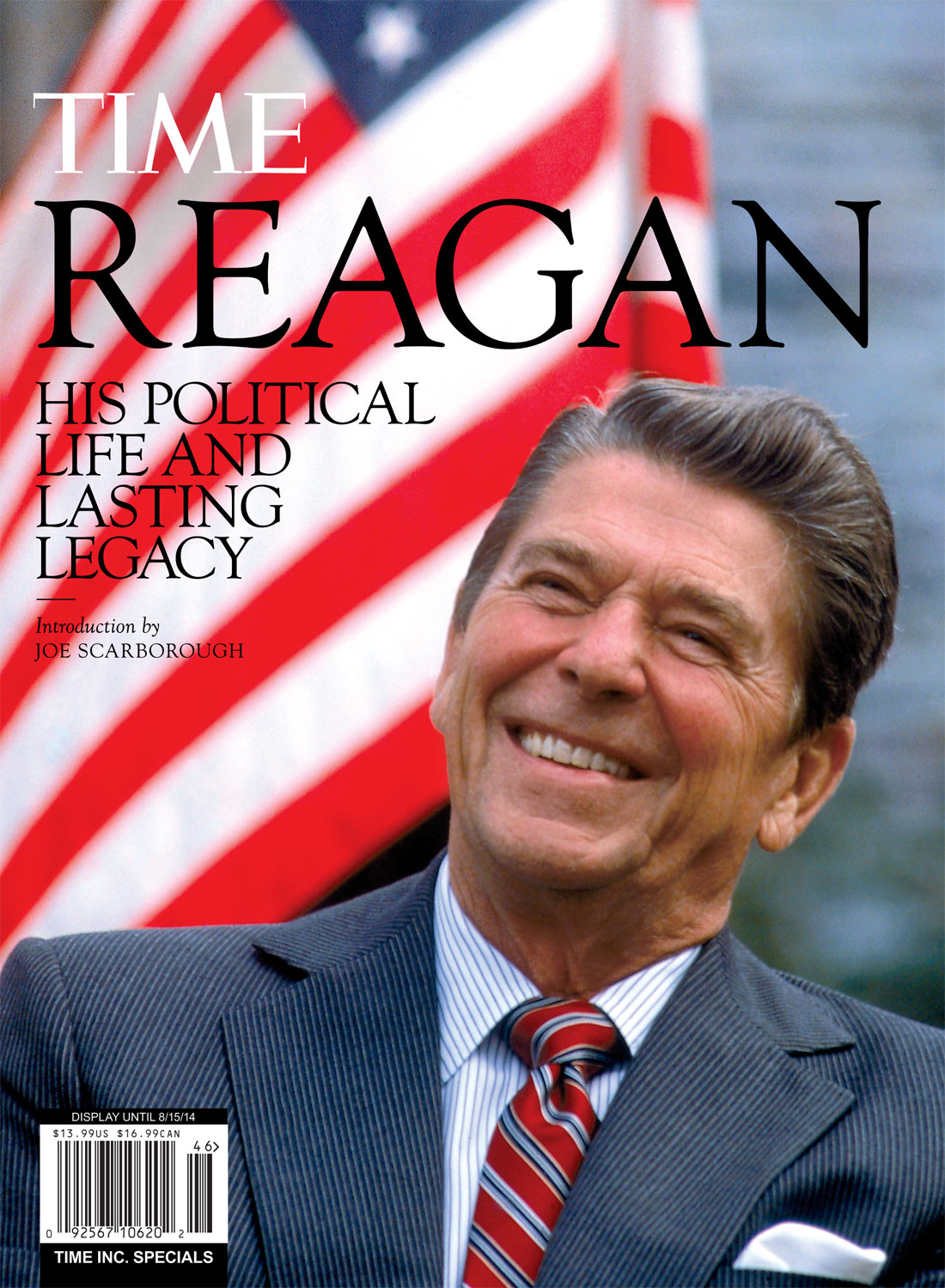

It is now 10 years after his passing, which is the occasion of this book. Looking back from this vantage point, Reagan’s legacy remains vivid and potent. How else to explain how a conservative movement and political party continue to obsess over the question “Who is the next Reagan?” And as his Republican Party is slowly learning, it is a frustrating question and may, in fact, have no answer, because Ronald Wilson Reagan was unique.

It makes no more sense than for Democrats to search for the next Franklin D. Roosevelt or military leaders to seek out the next Dwight Eisenhower. These men possessed certain skills for their times that allowed them to bend history for all time. There is no guidebook for such greatness.

In law school we learned the Latin phrase sui generis, which means “of its own kind” or “unique in characteristic.” Reagan was of his own kind. Reagan was unique. He believed in God, the American people and himself—and knew how to communicate those values in a way that no conservative has before or since.

Yet Reagan the conservative was a man as focused on America’s glorious future as he was on preserving the values of the past. He was no reactionary. He was, instead, the iconic American who believed in what was yet to come. This had been the hallmark of American exceptionalism since Thomas Paine told his fellow citizens they could remake the world.

Those men who gathered in Philadelphia set a course for America that has always pointed toward the future. Along the way, our ship of state was violently tossed by slavery, a historically bloody civil war, a staggering depression and two world wars. But America was sustained by its people’s inner strength and determined optimism. Men like Reagan continued to believe that the United States was headed toward a brighter future—until they hit the turbulence of the ’60s and ’70s, when the national identity felt tremors of doubt.

For a time, America stopped listening to her heart and her head. The wind was no longer in her sails.

In the span of 11 years, America lost a war and two presidents, one from an assassin’s bullet and the other by his own failings. A third was driven from office, chased by the chants of “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?”

The social and moral polarity of the American universe was upended. The antihero had become the hero, and American soldiers, returning home from the lost cause of Vietnam, were spat upon. An oil embargo, 21.5% interest rates and a hostage crisis fostered a malaise that spread across the nation. I still remember my fifth-grade teacher telling my class that, as had befallen the seemingly invulnerable Roman Empire, America’s days as a world power were quickly coming to an end.

Like my teacher, many believed Henry Luce’s American Century was over, 20 years ahead of schedule.

Ronald Reagan was born for a time such as this.

He was a figure derided by the elites of both political parties, Wall Street, academia and the national media. They said he was too simple, too unqualified and too inexperienced to lead the free world. His ideas were antiquated, and they predicted that his foreign policy would push America into a third world war.

Yet the millions of Americans who carried Reagan to huge victories in 1980 and 1984 felt that this was a man who was uniquely qualified to lead the country back to greatness. Reagan, after all, had been a conservative star, a successful labor leader, a two-term governor running the seventh-largest economy in the world and, yes, a Hollywood actor. It would take all of the Gipper’s on-screen skills to make his countrymen believe that the economy could be turned around, that the Soviet Union could be defeated, and that America’s greatest days truly did lie ahead.

John Jay, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, in pushing for the creation of a Constitution for the young country, argued that the most important considerations for a president were experience and character. The boy from northwestern Illinois had bushels of both.

He also had Nancy Reagan at his side, and she, as anyone who saw them together will attest, was his greatest treasure.

Ronald and Nancy Reagan won the White House by asking men and women from all corners of the country, including Democrats and independents, to join his “community of shared values.” Unlike many in today’s Republican Party, Reagan made an open appeal to Democrats on the campaign trail and at the GOP convention.

Reagan Democrats and independents answered his call for change. And then President Reagan changed the world.

My friend Craig Shirley, one of Reagan’s leading biographers, told me, “Reagan bends light and thus changes the future. He changes American conservatism, he changes the Republican and Democratic parties, he changes America and he changes the world.”

For Reagan, common sense was intellectualism. He also believed American conservatism was about challenging the status quo. Frederick Douglass, the great Republican abolitionist—whether addressing suffragettes in Washington, D.C., or a church congregation in Dundee, Scotland—summoned his lifelong rallying cry: “Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!”

Reagan and Reaganism were about agitating against the conventional wisdom of political parties and entrenched powers. The man who spent most of his life being mocked by Washington ended up changing it forever because, to paraphrase another Hollywood star, he frankly didn’t give a damn what his elite critics thought of him.

Reagan is ubiquitous now in American politics, cited often by members of both parties, who all too often don’t truly understand his brand of conservatism or the man himself. That makes the study of his life and times so vitally important.

Were his eight years in Washington defined by Hollywood glitz and glib politics? Certainly not. On occasion, did he compromise on such conservative touchstone issues as taxes, entitlement programs and immigration reform? Yes, but always with the longer view in mind. In the end, did he succeed? Consider this: America’s victory in the Cold War freed tens of millions imprisoned by communism across the world. Twenty million new jobs were created at home. Double-digit inflation and interest rates were wiped away. Unemployment fell to around 5.3% by the time he left office, and, more important, America’s national morale was restored.

Ronald Reagan had inherited a badly divided Republican Party and an even more fractured country, but as he flew west on the day of his retirement from national politics, he flew over a country more confident in its future than at any time since the 1950s.

John O’Sullivan of the National Review observed that “the fact” of America would always exist, but it was “the idea” of America that the 40th president restored. Shirley points out that well over 1,000 books have been written about Reagan, but for historians, “the realm of Reagan scholarship is just opening up. There is enough of Ronald Reagan for all of us to breathe.”

Some may be discouraged that there is no new Reagan on the horizon. But many, like myself, thank God that America got the leader it needed at precisely the right time and place.

Having him back might even be worth a Vice President Jerry Lewis.

This essay originally appeared in Reagan: His Political Life and Lasting Legacy.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com