President Barack Obama lanced the infected boil that has become the Department of Veterans Affairs Friday by accepting the resignation of Secretary Eric Shinseki. While that action removes the public face of the expanding scandal, it triggers a series of new complications that means the VA’s woes are far from over.

True, Shinseki’s resignation excises the political problems associated with him sticking around. But it does nothing to ameliorate the deep and persistent rot inside the scheduling schemes that led to lengthy waiting lists that may have contributed to ailing veterans’ deaths. “Ultimately, a change in leadership does not address the root of the VA health care system’s problems of access and appropriate funding levels,” said Joseph Johnston, the national commander of Disabled American Veterans, on behalf of his group’s 1.2 million members.

But Obama made clear—five times as he announced Shinseki’s departure—that Shinseki had become a “distraction” that needed to be jettisoned. This focus on “distraction” puts style over substance, and the President said as much. “The distractions that Ric refers to in part are political,” he conceded. Ending such distractions are important in an election year where members of Obama’s own party were growing insistent that it was time for Shinseki to leave. “We’ve also got to deal with Congress and you guys,” Obama told reporters. “Ric’s judgment that he could not carry out the next stages of reform without being a distraction himself. And so, you know, my assessment was, unfortunately, that he was right.

It will be vital for Shinseki’s deputy, Sloan Gibson, and whoever succeeds him (assuming Gibson is not tapped for the top spot), to convince the public that he is furious over what has happened at the VA. Shinseki, according to associates, was furious, but seemed incapable of showing it. That’s a big liability in today’s world, where sound bites masquerade as policy.

In a nutshell, Shinseki’s resignation offer—and Obama’s acceptance—took the wind out of the sails of a growing bipartisan chorus of lawmakers calling for Shinseki’s ouster. But the vacuum his departure creates does nothing about the agency’s deep and abiding problems:

The VA will be politically rudderless until a new secretary is confirmed, even as Gibson assumes control after having been in the No. 2 slot for only three months. The West Point graduate and former Army infantry officer headed the United Service Organizations—the USO of Bob Hope renown—that provides troops with war-zone concerts and airport lounges. “Everything we do at VA is built on a foundation of trust,” Gibson told Congress last month. His first task will be to try to glue that shattered trust back together.

Obama made clear he is seeking a permanent Shinseki replacement. It’s likely to take months before such a candidate is found and confirmed—and then additional time for Shinseki’s successor to get up to speed. “President Obama must move now to appoint an energetic secretary who is unafraid to make bold changes and work quickly and aggressively to change the VA system,” said Paul Paul Rieckhoff of the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America.

A new boss might not change much. “Those who surrounded Shinseki shielded him from crucial facts and hid bad news reports, in the process convincing him that some of the department’s most serious, well documented and systemic issues were merely isolated incidents to be ignored,” said Rep. Jeff Miller, R-Fla., who chairs the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. “Eric Shinseki trusted the VA bureaucracy, and the VA bureaucracy let him down.” The VA’s 300,000 employees and complicated rules combine to make such chicanery possible.

Candidates willing to subject themselves to the confirmation process—especially to take command of a troubled agency under intense public and congressional scrutiny—are likely to be few. The fact that the tenure in the job would likely be only about two years also decreases the attraction of volunteering for the slot.

The VA has three major responsibilities: taking care of veterans’ health, providing benefits if they are disabled, and tending to the nation’s 131 veterans’ cemeteries. With the notable exception of wait times, it gets good marks on health care. Benefit claims have been plagued by backlogs, which are slowly shrinking. All this means that any VA secretary has a lot to tend to, and that the wait-list issue is only a small part of the job.

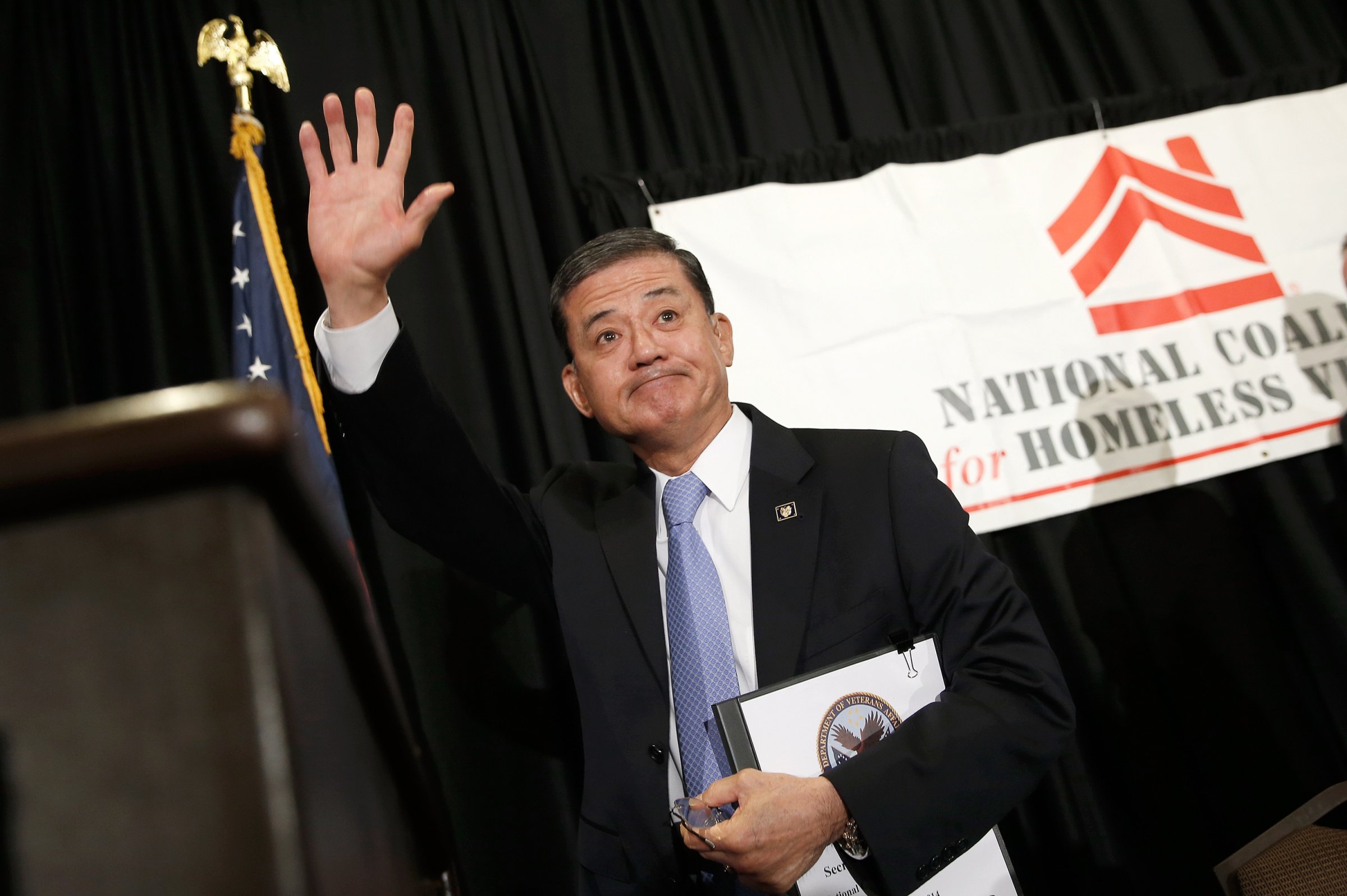

Shinseki appeared to be ready to go down fighting in a speech Friday morning to the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, a group advocating on an issue on which the VA has made major strides. He said he would be firing the leaders of the Phoenix VA, where delayed appointment may have contributed to as many as 40 deaths. (“I’m glad Shinseki torched Phoenix officials before he left,” former VA employee Alex Horton tweeted. “The amount of deadwood at VA could light a perpetual bonfire.”)

In his early Friday morning speech, Shinseki betrayed no intention of submitting his resignation to the President about an hour later.

“Since 2009, VA has proven that it can fix problems, even big ones,” he said, referring to the year he became head of the agency. As for the waiting-list mess? “This situation,” he insisted as he wrapped up his talk, “can be fixed.”

But after 38 years in uniform—and five at the VA’s helm—it just won’t be Shinseki leading that charge.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com