American artist James Casebere has been photographing dioramic constructions of human civilization since 1975. His tableaus—scenes from places both fictional and real—respond to current events and are the subject of a new book called Works 1975-2010, which chronicles highlights from his 35-year career.

Over the years, Casebere’s images have expanded and redefined to show his exploration of aesthetic technical challenges. “Photography resonates with me because it manipulates our perception of the world around us,” he says. “I am interested in photography as a means of persuasion, of propaganda and constructing histories. I am interested in how photography creates and reconstructs reality.”

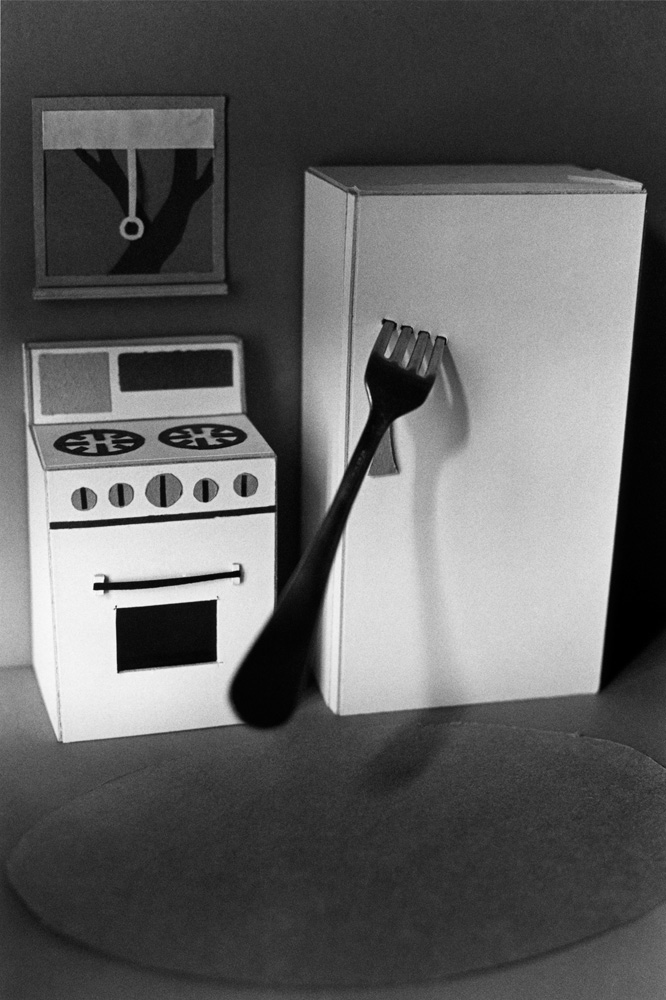

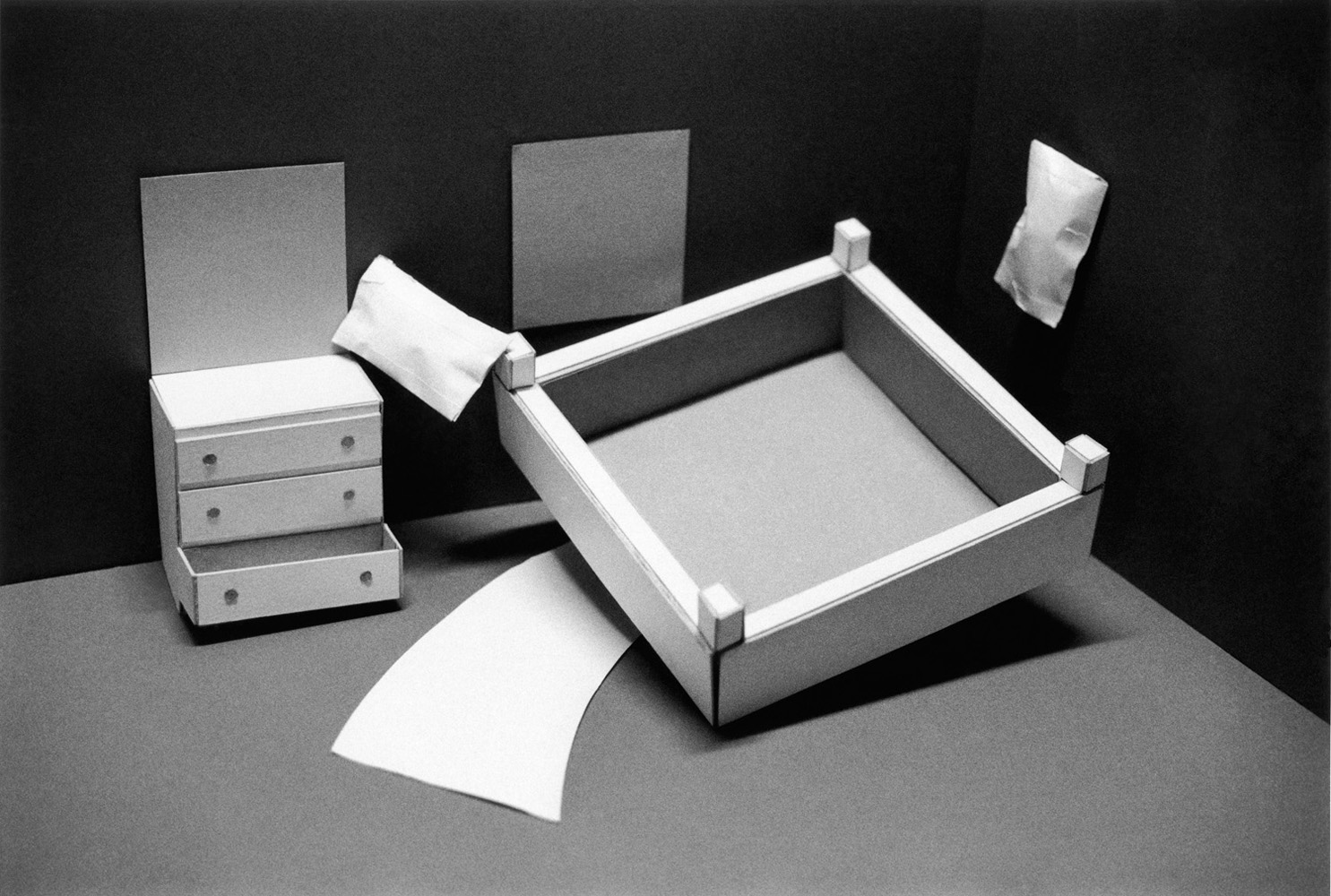

Born in Lansing, Michigan in 1953, Casebere grew up during the era of television’s rise to becoming America’s prominent medium for creating images and manifesting visual culture. Referencing the sets of sitcoms of the 1950s and 1960s, Casebere’s early career focused on disseminating and questioning the domestic household and addressing the growing dysfunctions of the ideal American home. Though the scenes that he constructs and then photographs are often similar to the environment of his native Lansing, the images are not anecdotal. This absence of a personal narrative is a strategy Casebere still continues in his work today.

Among Casebere’s most well-known work are his images of the interiors of detainment cells and prisons, such as Prison Cell With Skylight, 1993. “I was thinking a lot about the Enlightenment era and the way that different cultural institutions were created in the late 18th and early 19th century. One of the developments was the prison,” he says. “I wanted to investigate innovations of the whole system…I was trying to critically look at the whole process of incarceration as cultural-historical phenomena.”

Color became more focal and the construction of sets more filled with detail in the work that follows the prison images. Casabere began capturing interior rooms beginning in the mid-90s, with images like Converging Hallways from Left, 1997. “When I was working on prisons, I was really dealing with a subject that involved deprivation and denial,” he says. “When I moved to the interior spaces, they were less obviously models—they were more convincing. The images are printed quite large, and when viewing them in a gallery, they really become something one can walk into. There was confusion about what is real and what isn’t…There came a moment when I decided to break down the wall, visually— to do things with color, light and texture— literally, to break down the walls, the construction of the models.”

At times, Casebere’s work seems to be indicative of future events. Images that Casebere created from 2006 through 2007, seemed to almost foreshadow this year’s Arab Spring, addressing issues that were boiling in the Middle East for a long time. The images depict the Middle East from a place of brewing conflict, but also a place where people lead normal lives. “I was really trying to create a different impression entirely. Tripoli, 2007, the image that I photographed is actually a recreation of Tripoli in Lebanon,” he says. “Shortly after I made that image, there was a battle at a refugee camp, where the Lebanese army surrounded the village and drove them out.”

Casebere’s latest series of images, each work titled a numerical variation of Landscape with Houses (Dutchess County, NY), reveals his return to focusing on the domestic, a move influenced in part by the advent of the mortgage crisis. But this time around, the artist brought color and dramatic lighting into the work. “I was really working with the lights, recreating morning light, afternoon light, evening light, twilight, moonlight, all kinds of light to exhaust the possibilities and color,” he says. The latest image in the series, however, depicts the idyllic suburban houses with a catastrophic, albeit humorously cartoonish, fire burning in the background. “The fire is metaphoric of the sense of crisis of living in the home, the loss of the American dream,” Casebere says. “I emphasize and criticize [the fact] that we’re caught in a cyclical lifestyle that is destructive and self-destructive.”

Works 1975 – 2010, was published this month by Damiani and distributed by D.A.P.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com