In his new book, the filmmaker investigates the mysteries behind some of photography’s most famous news images. Here, Morris walks TIME through five of his fascinating case studies:

TIME: In your first case study, the Crimean cannonball photos (slides 9 and 10), you write about how we can often make certain assumptions about a photographer’s intent that can misdirect us from the truth. How did that play out in these two pictures?

First off I want to say that I don’t think photographs are true or false. I always associate truth and falsity with language, rather than images, photographic and otherwise. People become endlessly confused because they think that some photographs are more true or less true than others, and they get trapped in a strange set of arguments that I believe lead nowhere. If one photograph is more true than another, then you ask yourself, are there things I can do to guarantee the truth of a photograph or to make it more truthful.

Your question was about the intent of a photographer. One of the things that people are most concerned about is the intention to deceive, to trick us, to lead us astray. Well, this pair of photographs, taken in 1855 by Roger Fention, is one of the very first war photographs. A barren landscape bisected by a road littered with cannonballs. The photographs are identical except that in one there are cannonballs on the road and in the other, there are not.

And it leads people to speculate, without even knowing they were speculating, about the order of the photographs, why there are cannonballs on the road in one and not in the other. And I used this as a way to examine our attitudes towards photographs, how we often read things into them things which weren’t there in the first place.

And at one point I even suggest that by thinking about this pair of photographs, we are really examining the nature of photography in general. So I ask a reader to go on an excursion with me. I like to think of them as little mysteries. To try to look at photographs, to try to think about what our assumptions are about them and to accompany me on an investigation into what we’re really looking at.

TIME: In writing about documentary photographs, you say that, in essence, every shot is posed because the photographer always chooses what and what not to include in the frame. I don’t think the average viewer—whether they are seeing a picture in a newspaper or a magazine or a museum exhibition—ever thinks about the fact that each photograph involved a decision of what not to include as much as it did what do include.

Photography is in part how I make my living, and I think about photography and photographs all the time. When you’re creating an image—and most of the images I create are in truth aren’t still images but motion picture images—but when you create an image, I often think about what I’m not including as well as what I am including. Images in part derive their power from the fact that we are excluding so much of the world. They’re focusing our attention in a way they it might not be focused otherwise. I can’t remember my exact wording, but somewhere in the book I talk about how photographs are ripped from the fabric of reality. I like the idea that they are torn out of reality. And we look at them and we don’t see above or below or to the left or to the right, we just see what’s inside the frame. And that’s easy to forget about.

TIME: Something that was apparent to me in your next case study was that sometimes the people who should be skeptical about photographs aren’t. I’m talking about the hooded man photo. The New York Times ran a story that identified a man as the person in that famous photo (slide 8), but it wasn’t him.

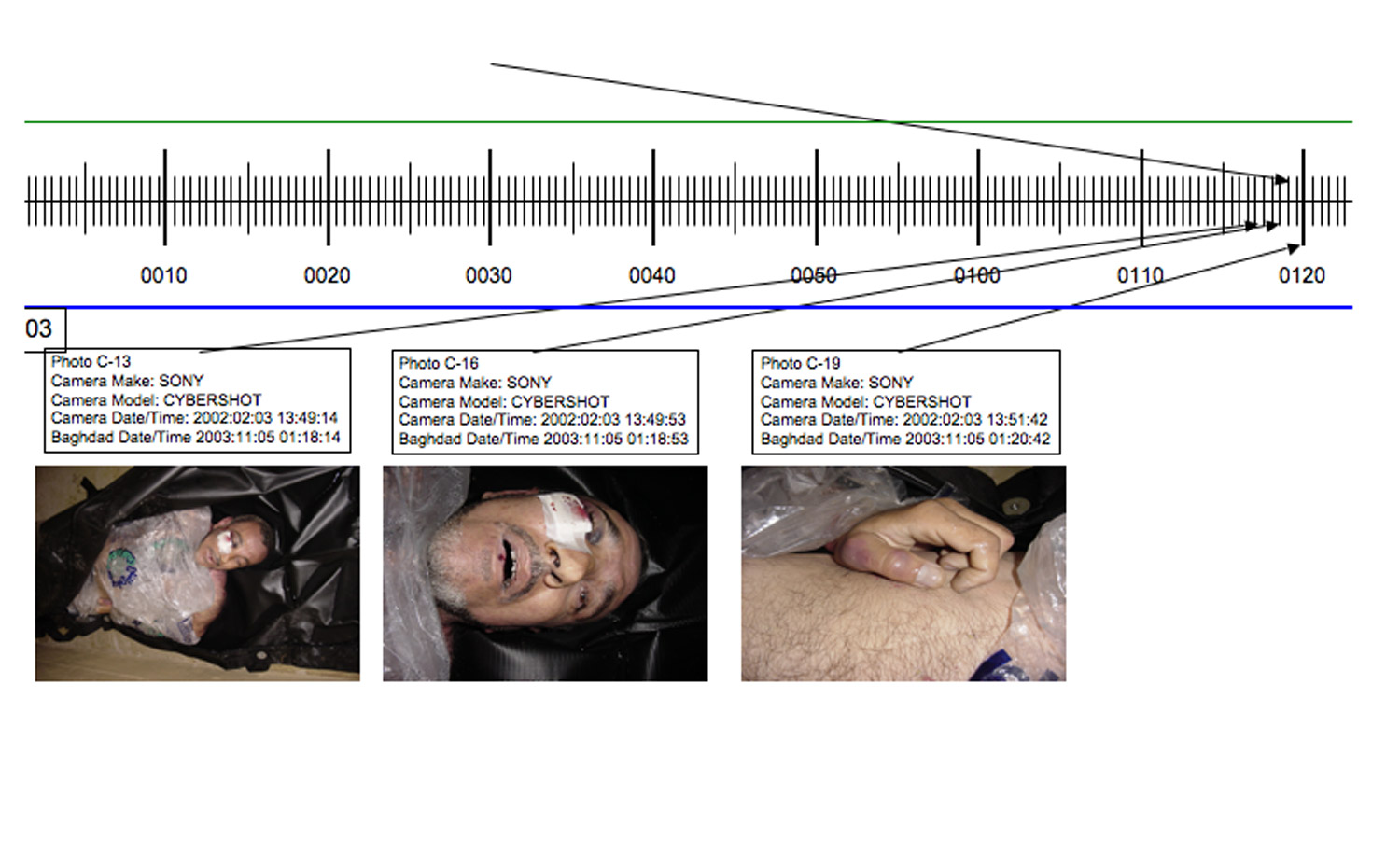

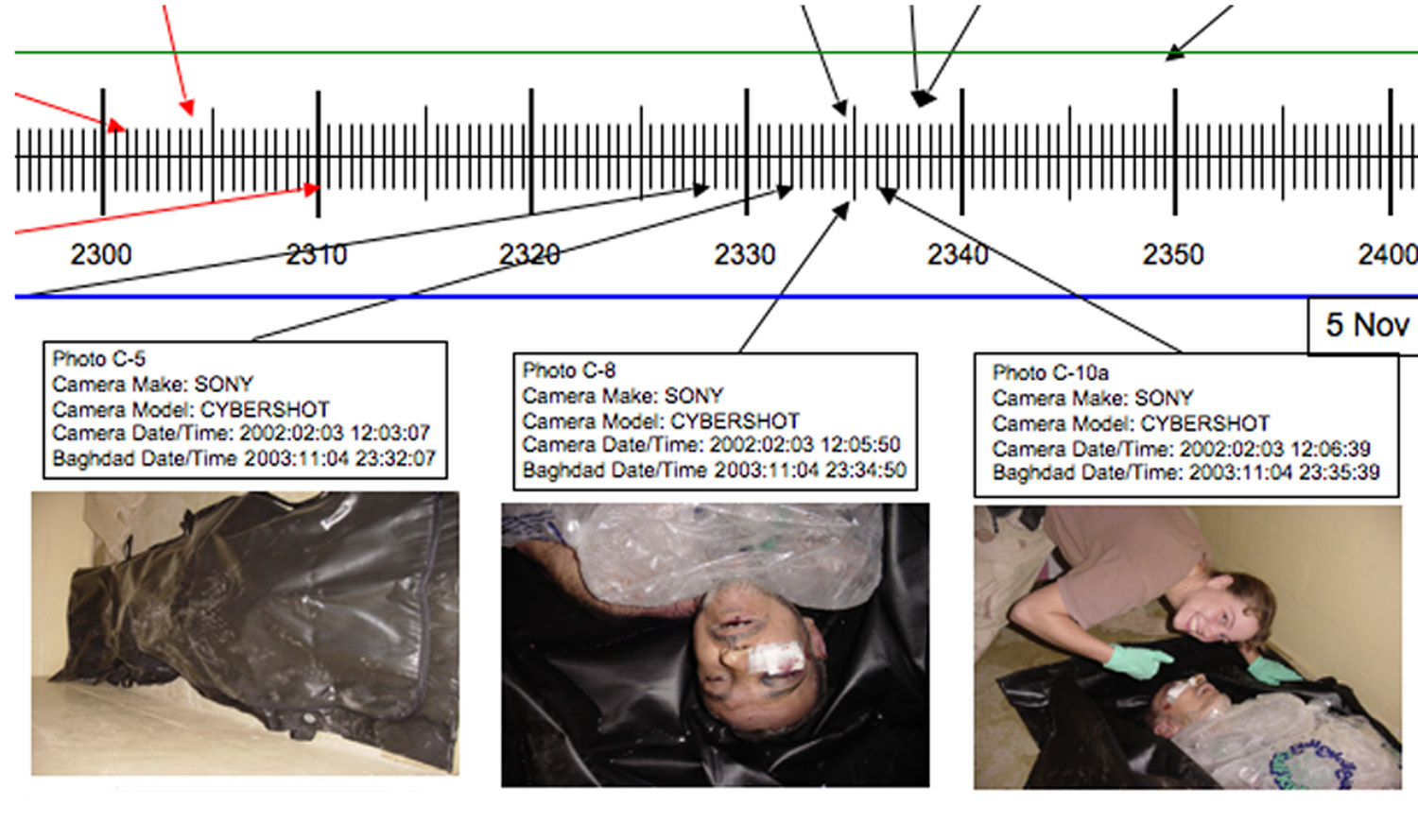

It’s probably the iconic photograph of the Iraq war. Photographs become iconic because they resonate with people for all kinds of reasons. And that photograph has been seen by hundreds of millions of people. A number of people said to me, “Well why do you care who’s under the hood? Does it really make any difference? After all, the photograph is not about who’s under the hood, it’s about torture, or it’s about these crimes committed at Abu Ghraib in 2003. Why do you care about the specific details of who it was?” And I would say that I care about both. I care about how photographs are received and viewed by people, but I also really care about their connection to the underlying world. It’s part of the mystery for me. What is it that I’m looking at? Yes, there are well-received beliefs about this photograph, but what really are we looking at? And usually you can’t determine that from just looking at the photograph itself. Usually you have to investigate. Usually you have to look further. And part of what interested me about the Abu Ghraib photographs is that a lot of people were aware of them in this country and abroad, people had views about them, and they made people very very angry for many different reasons, but no one had seemingly bothered to actually try to contextualize them, to try to investigate what it was that we were looking at, as if it was obvious.

And I have an expression that I’m fond of, which is that nothing is so obvious that it’s obvious. It’s usually when we think things are obvious that it’s time to actually look further and to try to look at our underlying assumptions. And by the way, you can investigate and you can come up short. You’re not guaranteed to solve every mystery that you set out to solve. We tried so very very hard to find the guy, the real guy, and came up short.

TIME: With the Sabrina Harmon photos (slides 6 and 7), we first saw them and saw her smiling over this dead body and that smile implied guilt even though it turns out she didn’t do anything—she didn’t abuse the prisoner, she didn’t kill him and she’s not genuinely smiling. But we automatically think that this woman helped beat this guy up and kill him.

We have problems with ambiguity and unresolved mysteries. We also have problems with complexity. Often there’s a need to see people as heroes or as villains rather than in some gray area in between. It’s easier to navigate through life that way. I was criticized for defending Sabrina Harmon. After all, what these bad apples did was terrible. A disgrace. And I am seemingly an apologist for what they did at Abu Ghraib. And I would beg to differ. Take this photograph of Sabrina Harmon and the corpse of Al Jamadi—I was trying to contextualize that image, to put it back into history, and I learned some very surprising things.

In the case of Sabrina. She took a whole range of photographs of that corpse, many of which were to document what she thought was a crime. This man had been beaten to death, presumably by a CIA operative. She had not been involved in any way. She had merely recorded the aftermath of this crime. And she, as indicated in her letters to her girlfriend she felt there was a cover-up going on and that she was going to expose it.

So we look at the photograph and think we’re seeing perhaps a murderer gloating over their crime. And, in fact, what we’re see is something very different.

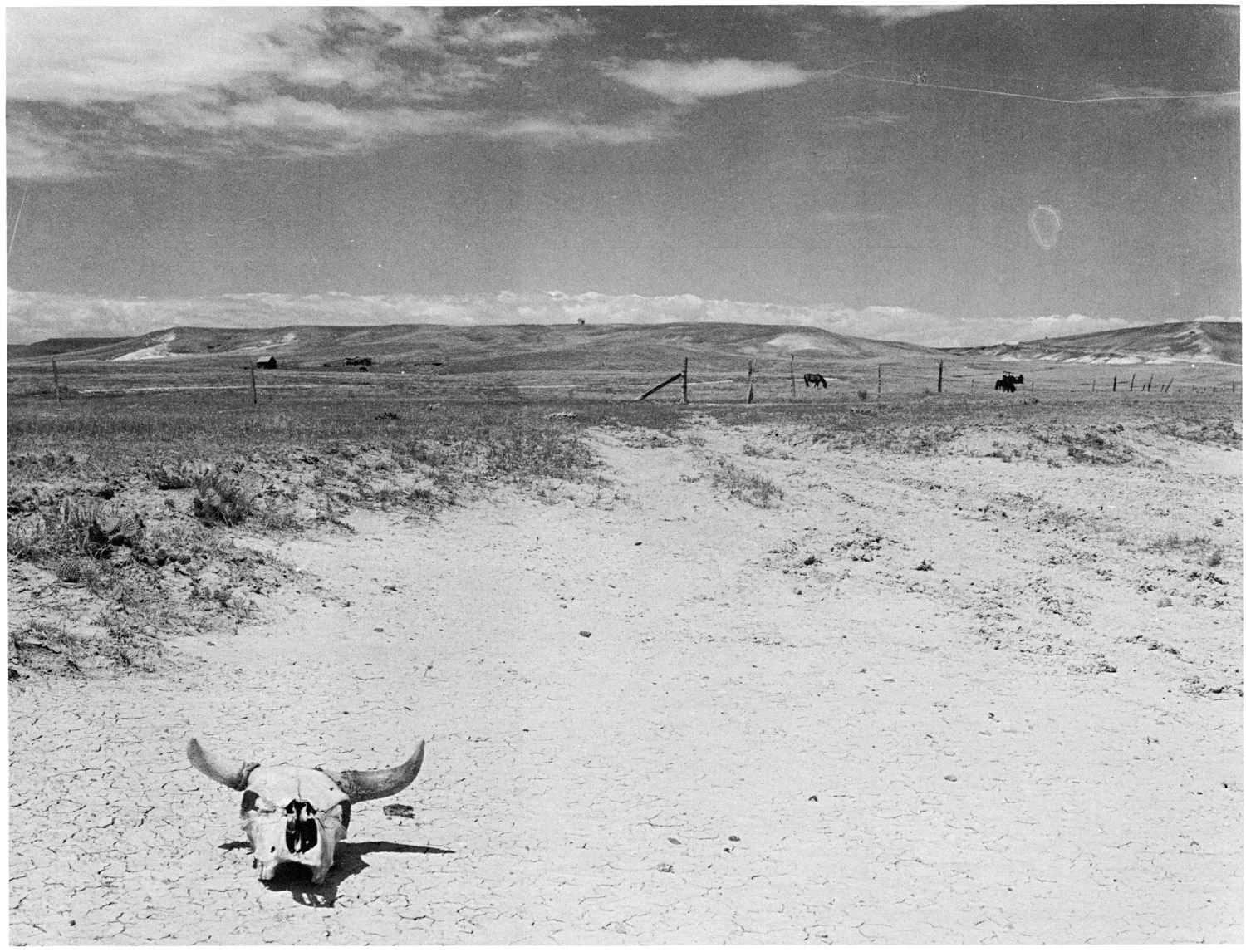

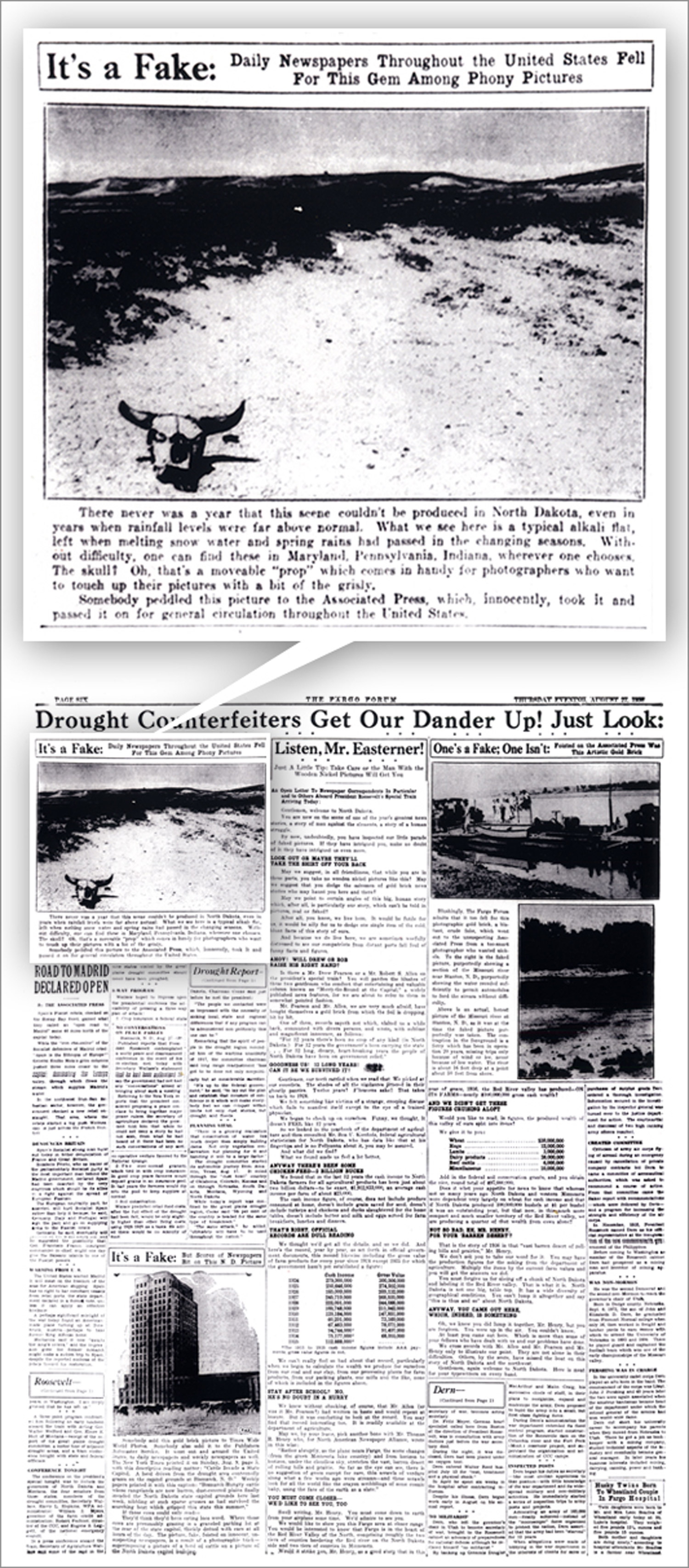

TIME: At one point, you write the following: “While the technology may have changed, the underlying issues remain constant: When does a photograph document reality? When is it propaganda? When is it art? Can a single photograph be all three? That’s you writing about the Rothstein cow skull photo (slides 1-3). What’s the story there?

The Roosevelt administration had created the FSA, the Farm Security Administration, and they in turn hired photographers who were to become the most famous in history—Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein, Dorothea Lange. These are among the great American photographers of Depression-era America. And they took literally thousands of photographs under the auspices of the government. And Rothstein was sent to the Dakotas to document the drought. And he took a photograph of a cow skull in what looked like to be a close to desert landscape. And this photograph was published in newspapers around the country as an example of how bad the drought had become in the Dakotas.

Well Rothstein did something—you could call it a mistake—he did something that created almost instant controversy when they found out about it. He had moved the cow skull to five or six different locations and photographed it. Now when people became aware there was more than one cow skull photograph and that he had moved them, for artistic purposes is what he argued, he was trying to get a really good shot with the right shadows of the cow skull. Then people say, “Well why that picture and not this one, and what were you doing, were you moving the cow skull? Were you manipulating the photograph to trick people?”

Well here’s the central irony. Here’s one of the ironies. You look at the photographs and you think, ooh, there was a drought. And guess what? There was a drought! Did the fact that he moved the cow skull suddenly invalidate that photograph? Well, you have to know something about the circumstances under which it was taken. And I did try to investigate that issue.

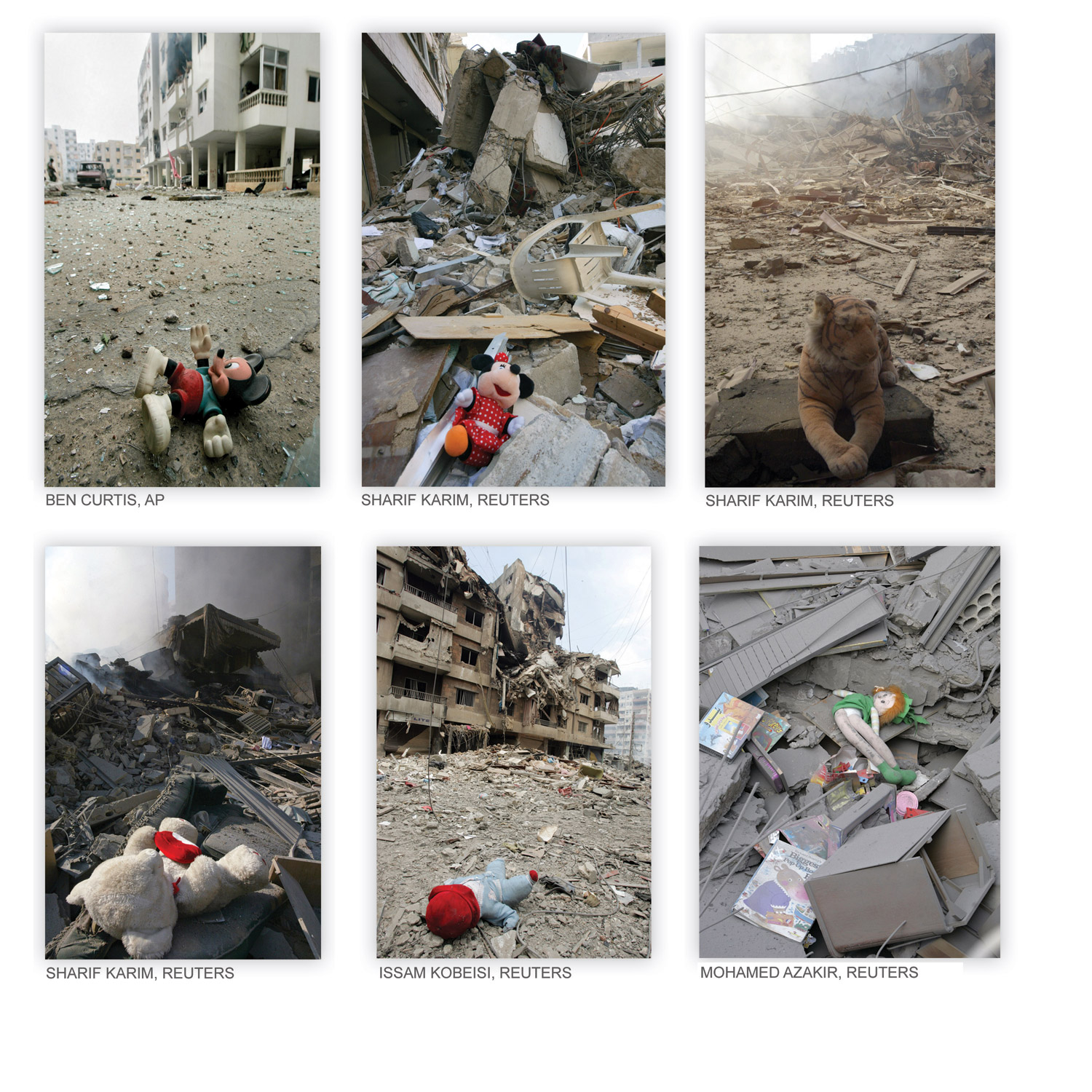

TIME: Finally, let’s talk about these Mickey Mouse in Palestine photos. You have a wire photographer, you have this picture of Mickey outside a bombed out apartment complex in Lebanon (slides 11 and 12). There are questions of agenda, of whether the photographer moved the mouse there, of whether the selection alone implied a bias.

These toy photographs, there was a whole collection of them that came out of Lebanon. And the claim was that pro-Palestinian, pro-Hamas photographers are, the way I imagined it, was that they were appearing in the war zone with a big bag of toys and distributing them and taking pictures of them with the intention of misleading people. One way to look at it is that Israelis are killing Palestinian children.

One of the well-known photographs of a toy taken in Lebanon, in southern Lebanon was taken by this Associated Press photographer Ben Curtis. Another irony. That we think we know how that photograph is going to be used, but it was used in just the opposite way in a newspaper than I would have thought, in an anti-Palestinian op-ed. It shows how photographs can, the meaning of them, or what we take to be the meaning of them, can be so easily changed by the context that we place around them, the new story we place around them—the caption that we put under them can change everything.

Believing is Seeing was published by Penguin Press.

Gilbert Cruz is a senior editor at TIME. Find him on Twitter at @gilbertcruz. You can also continue the discussion on TIME’s Facebook page and on Twitter at @TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com