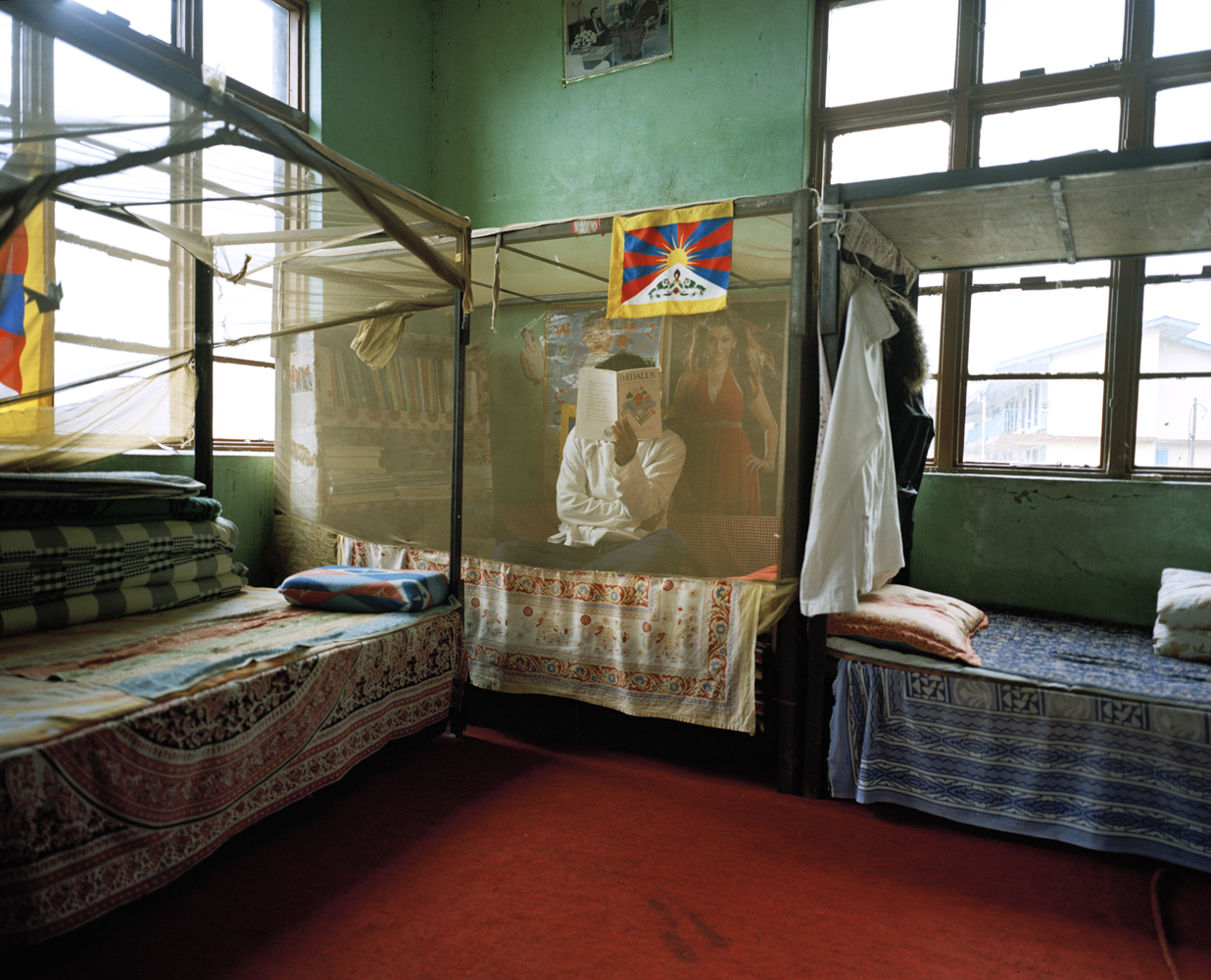

The world is filled with millions of exiled peoples, whose plights are as obscure as they are tragic. But the exiled Tibetan community in the Indian hill station of Dharamsala, which coalesced five decades ago after Beijing exerted its control over the high plateau, is an exception. Its spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, is far more famous than any living leader in China, the country that rules repressively over Tibet. From dilapidated offices with slow Internet connections, this displaced populace has orchestrated a Free Tibet cause that has turned what might otherwise have been a forgotten ethnic struggle into a chic crusade worthy of Hollywood’s concern. In August, photographer Sumit Dayal and I traveled to the scruffy Himalayan foothill settlement to meet some of the 150,000 Tibetans who live in exile worldwide and who have turned Dharamsala into a Little Lhasa.

For Dayal, the trip was a homecoming of sorts. An Indian whose family is originally from Kashmir, Dayal grew up in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital, where his playmates included the children of Tibetan refugees. (Nepal has a Tibetan exile population of around 20,000.) Dayal’s grandmother, it turns out, lives just down the hill from the Tibetan community in Dharamsala. By the end of our stay, we joked that every time we turned a corner—there are not many in this tiny town, and the monsoons kept us huddled under the same cover—we would run into someone we knew. Even the dogs gave us familiar sniffs through the rain.

But despite its small size, Dharamsala is the nerve center of a remarkable operation to publicize the Tibetan campaign. The trouble is, no one quite knows how to change the bleak reality back home or how, even, to return. Generations of Tibetans have been born in exile, such as Lobsang Sangay, the new Prime Minister of the Tibetan government in exile. To them, Tibet is as distant as it was to the Western romantics who considered it Shangri-La.

Some of the recently arrived refugees we met had been jailed back in Tibet; each had a perilous tale of escape to India through Nepal. A good proportion of the newest arrivals are children, whose parents sent them through paid guides to Dharmasala for a good education—even if they know this means they may never see them again. Their gamble is this: for a proud Tibetan, life in an Indian hill station where sacred yak-butter sculptures melt in the heat, may be better than home.

Sumit Dayal is a freelance photographer based in New Delhi, India. More of Dayal’s work can be seen here.

Hannah Beech is TIME’s China bureau chief and East Asia correspondent.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com