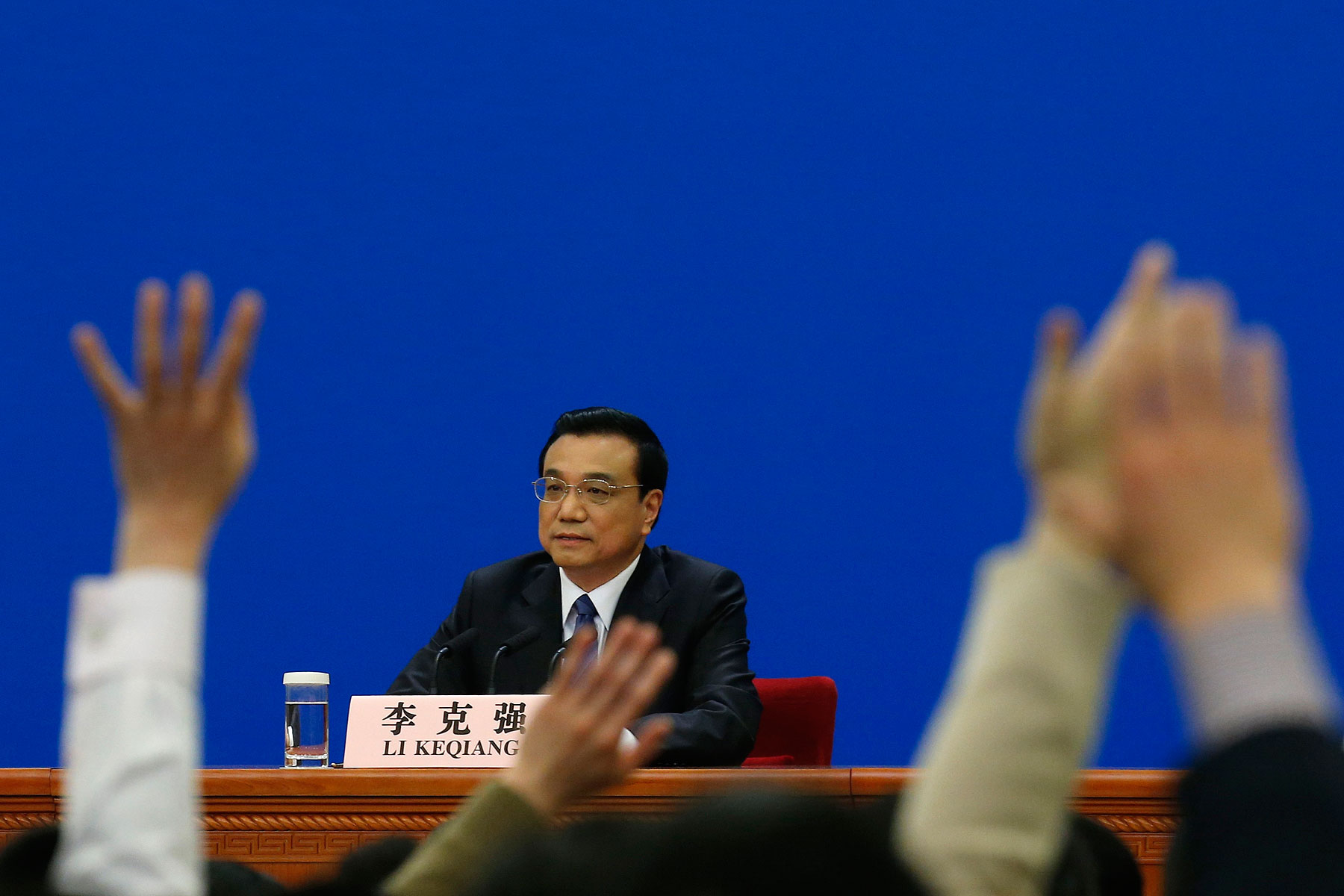

It was the one question the Chinese public (not to mention the Beijing press corps) was awaiting. The scene was the annual press conference with China’s Premier Li Keqiang at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People. Actually, the words “press conference” make the session that closes the National People’s Congress sound like a spontaneous event. Rest assured that the Q&A with the Chinese Premier is a meticulously scripted affair.

The journalists chosen to ask questions on the morning of March 13 were contacted beforehand. There’s negotiation — at least from some foreign reporters — about exactly how the queries will be phrased. But there are to be no surprises at the triumphal end of China’s annual legislative session. This pre-screening ensures that the Premier somehow has all the right facts and figures available to respond in great detail. There are even ringers brought in who are instructed to raise their hands with great enthusiasm. As Li slogged through his answers, journalists took bets on how long it would take for the news-making moment to arrive.

Li uttered disquisitions on the mystery surrounding Malaysia Airline Flight 370, which disappeared without a trace on March 8 with 153 Chinese passengers on board (Li: “families and friends [of passengers] are burning with anxiety” and “as long as there is a glimmer of hope,” China will not halt its search for the missing airliner) and the greatest challenge for China last year (Li: “increased downward pressure on China’s economic growth”). He vowed that “we need to loosen the straightjacket on businesses” and mentioned the hot term “rule of law” a couple times. Li acknowledged the severity of China’s air pollution problem, guaranteeing “a war on our own inefficient and unsustainable model of growth and way of life” and noting that the first thing many Chinese do upon waking is to check pollution-index aps on their cellphones.

But the question in question never came. For months now, a dragnet has appeared to tighten around Zhou Yongkang, who oversaw China’s massive surveillance state until his retirement in late 2012. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping and Premier Li, China has launched an anti-corruption crackdown that has netted hundreds of wayward officials. President Xi has promised to nab both lowly “flies” and high-ranking “tigers.” If Zhou, he of the Mafioso slicked-back hair and steely gaze, is indeed probed, he would be the mightiest tiger to be felled in decades. After all, he was a member of China’s elite ruling circle: the then nine (now seven) men of the party’s Standing Committee who determine the course of the People’s Republic.

Over the past year, a slew of officials high and low who worked under Zhou in three main spheres — the state-owned oil industry, the populous province of Sichuan and the Public Security Ministry — have been detained. His son and top aides have been implicated in nefarious financial dealings. Zhou himself may be under house arrest. All of which led some China-watchers to expect that Premier Li would use a pre-approved question at his press conference to at least indirectly refer to the state’s possible case against Zhou.

Li did not. In an annual press conference remarkably devoid of actual news, the Premier did take on a question about corruption; it was the third one asked of him and was lobbed Li’s way by a reporter from the online arm of People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist Party’s mouthpiece. Li’s voice took on a stern tone as he swore “zero tolerance” for corrupt cadres. He vowed that no matter “how senior his position is [corrupt officials] will be severely dealt with and punished to the full extent of the law.” Li promised that “everyone is equal before the law.” But, despite the People’s Daily reporter asking specifically whether there was anything systemic that could be changed, Li declined to tout an easy tool to combat corruption among party ranks: asset disclosure. Granted, releasing such financial information is a rather touchy subject in a political culture where profiting from power is almost expected.

More importantly, no names — certainly not Zhou’s — were named. Two years ago, at the final press conference by outgoing Premier Wen Jiabao, he launched a not-so-oblique attack on Bo Xilai, the former party chief of the southwestern metropolis of Chongqing and an aspirant to the Standing Committee. One day after Wen’s press conference, the Bo purge began. It was a dramatic downfall that involved a poisoned British businessman, a murderous wife and a cache of absconded public funds. Bo’s case turned into China’s biggest political scandal in decades. (Zhou was considered to have been Bo’s political patron.)

As the minutes ticked by in Li’s presser, expectations rose. After all, former Premier Wen had dispatched his tirade aimed at Bo toward the end of his press conference. Before answering his penultimate question, Li noted that it was time for lunch. Journalists must be hungry. A question followed on China’s trading relations with Europe — specifically to do with high-speed rails, nuclear power and solar panels. Then came the last question, the subject of which I’ve frankly forgotten. Suffice it to say it was not about Mr. Zhou. Reporters were dismissed for lunch.

On Weibo, China’s lively although occasionally censored microblogging service, people digested the press conference. One popular strain of commentary wondered why no mention had been made of Zhou. Wrote one Weibo user: “I’m very puzzled, why did the journalists, especially the foreign journalists, not cherish their opportunity to ask questions? Don’t they know Master Kang is the most delicious one?” (Zhou’s name is blocked on Weibo searches so Chinese online use creative nicknames like Master Kang to evade the state censors.) Apparently the Weibo commenters were not aware of the scripted ritual. In fact, in a meeting with a senior Chinese official some weeks back, some of us in the foreign press community had already been warned that a question on Zhou was verboten.

Meanwhile, the day before Li’s press conference began, a bloodied man was found dead in the stairwell of a securities’ firm off Beijing’s Financial Street, one of the Chinese capital’s business areas. Police said the man had ended his own life with a knife. His will was discovered. The dead man, according to Chinese media reports, is related to a former secretary to a senior leader currently under investigation. The Chinese press did not name the disgraced politician but he appears to be none other than Zhou Yongkang.

—with reporting by Gu Yongqiang/Beijing

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com