Updated: May 1, 2014, 11.45 a.m. E.T.

The U.S. Army’s new rules on the wear and appearance of insignia and uniforms — which include restrictions on tattoos — were issued on March 30, 2014, with a 30-day window of enforcement, and have now come into effect.

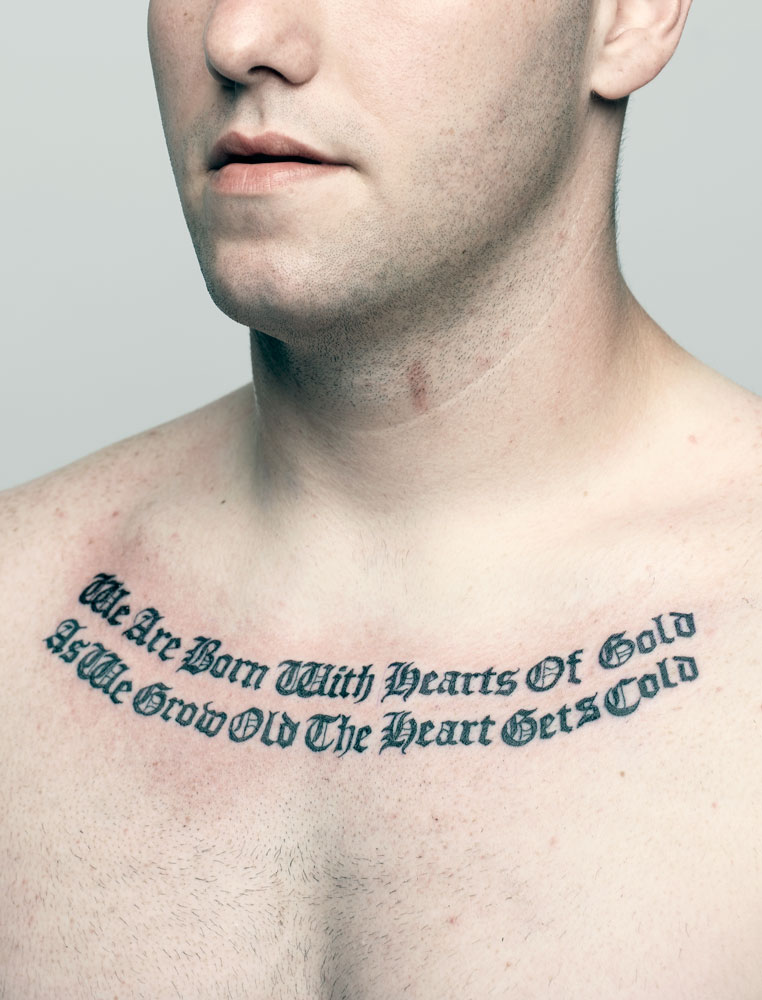

The new rules not only place limits on the number of tattoos a soldier can have, but on the size of every visible tattoo itself: In short, all new inkage should be no bigger than the wearer’s open hand. However, the army is allowing many soldiers to keep the tattoos they already have provided they are not deemed extremist, indecent, sexist or racist.

America’s troops too often come home from war only to remain a step apart from the rest of the nation. The chasm between the military and civilian populations has never been greater. It’s simple math: Less than one percent of Americans now serve in the military, compared with 12 percent during World War II. So after a decade of unrelenting war, with some soldiers and Marines serving four or more combat tours, many Americans still don’t know a single soldier, sailor or airman.

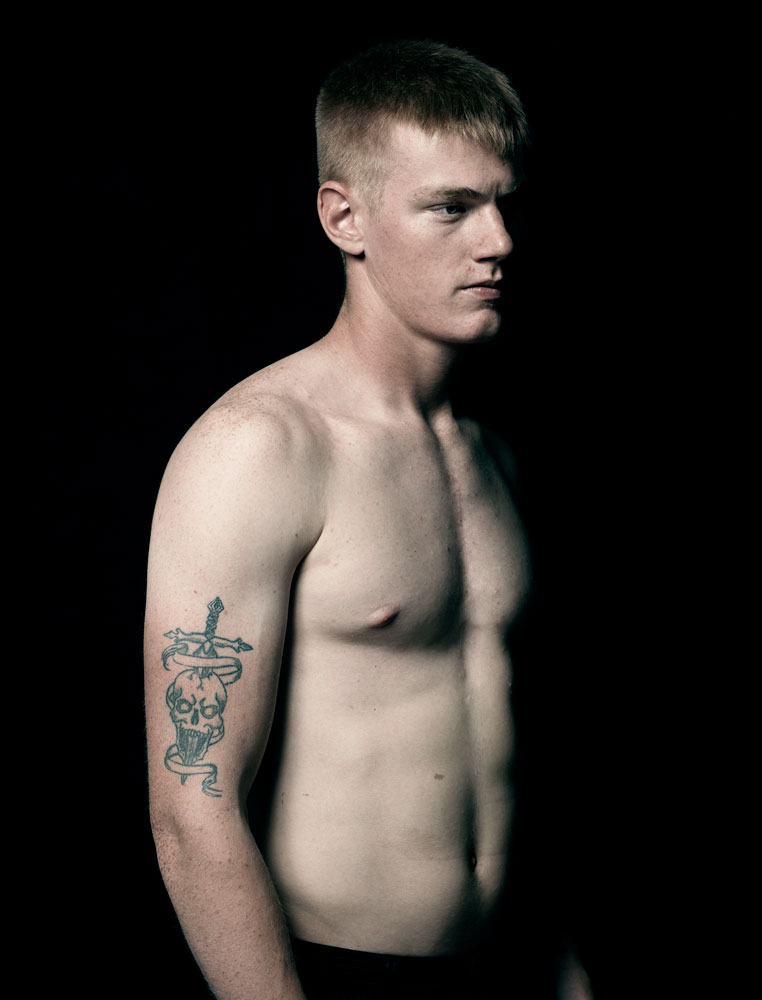

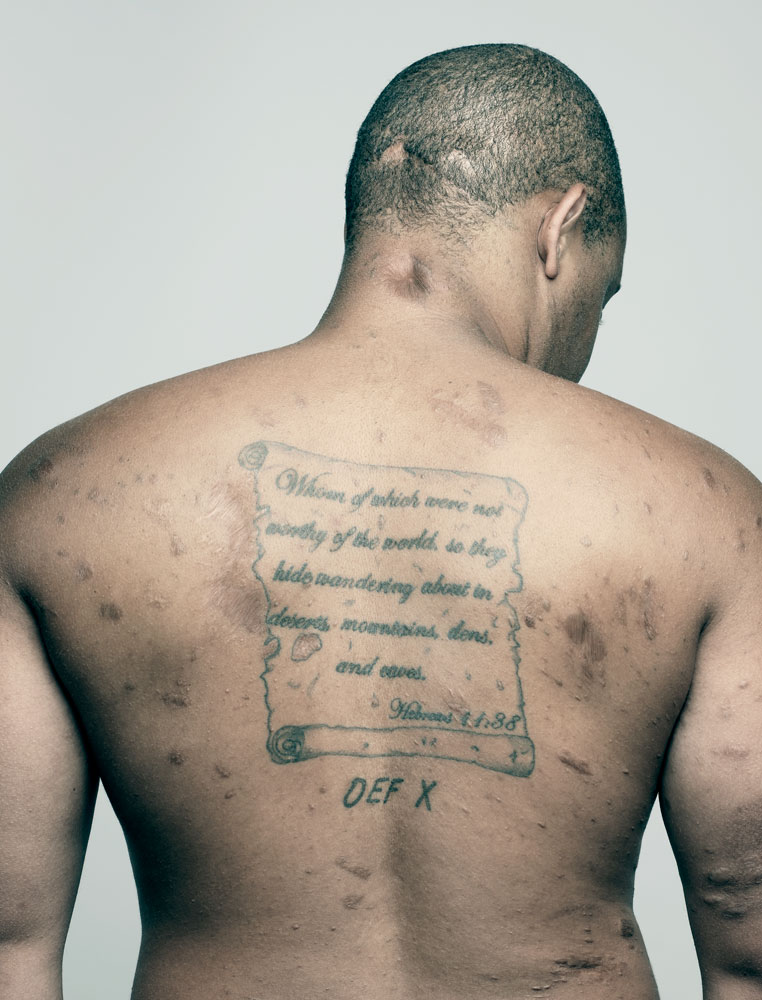

Veterans will tell you that one of the most jarring experiences of their service is the sudden immersion back into a society seemingly unaware that there are any wars going on at all. While they fought, their country went about its business. So they must find their own ways to acknowledge their experiences. A common ritual is the commemorative tattoo. Troops honor fallen buddies, venerate their units, reiterate war mottos, engrave themselves with religious prose, or dream up art that reflects experiences they might not talk about.

Since 1992, Capitol Tattoo has been inking the bodies of returning soldiers in a storefront shop on Georgia Avenue in Silver Spring, Md., just north of Walter Reed Army Medical Center, the massive Army hospital that is in the process of closing. “They are our family,” says owner Al Herman, of the soldiers who come in for artwork, or just to hang out.

On one day this summer, Herman opened his door to photographer Peter Hapak. The veteran clients rolled up their sleeves, stripped off their shirts, and revealed their scars, hoping that the resulting images would help bridge the chasm of understanding.

Mark Benjamin is an investigative reporter based in Washington, and a contributer to TIME, as well as TIME.com’s military intelligence blog Battleland. You can follow him on Twitter at MarkMBenjamin

MORE: Read Mark Benjamin’s magazine story, “The Art of War,” from this week’s issue of TIME [available to subscribers here].

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com