Updated May 21, 2014. Stephane Sednaoui’s work will feature in a standalone exhibition space at the 9/11 Memorial Museum — which opened to the public today — and will be on view for approximately nine months. This will be the first in a series of special, single-photographer exhibitions at the museum.

Stephane Sednaoui’s images, published here along with his e-mails in the aftermath of 9/11, are a unique and detailed document of Ground Zero in the days immediately following the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center.

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, photographer and director Stephane Sednaoui awoke to a very loud plane flying low over his downtown apartment in New York City. Having been raised in Paris where the airspace is kept clear, Sednaoui had always thought it was risky to have planes flying directly over Manhattan. That morning his fears were realized when he heard a matted explosion; looking out of his window, he saw the World Trade Center’s North Tower ablaze. Sednaoui ran to his roof and within minutes was taking photos and filming the unfolding scene. “In a dramatic situation” Sednaoui says, “looking through the frame of my camera allows me to control my emotions and try to rationalize the horror going on before my eyes.”

That afternoon, Sednaoui went to Tribeca to volunteer for the search and rescue effort at Ground Zero. A soon-to-be father (his daughter was born a month later), he says his intention was “to help find survivors.” The area was closed off the first night, but Sednaoui was able to reach Ground Zero on the evening of Sept. 12, staying there for three nights until the site was closed to volunteers on Sept. 17.

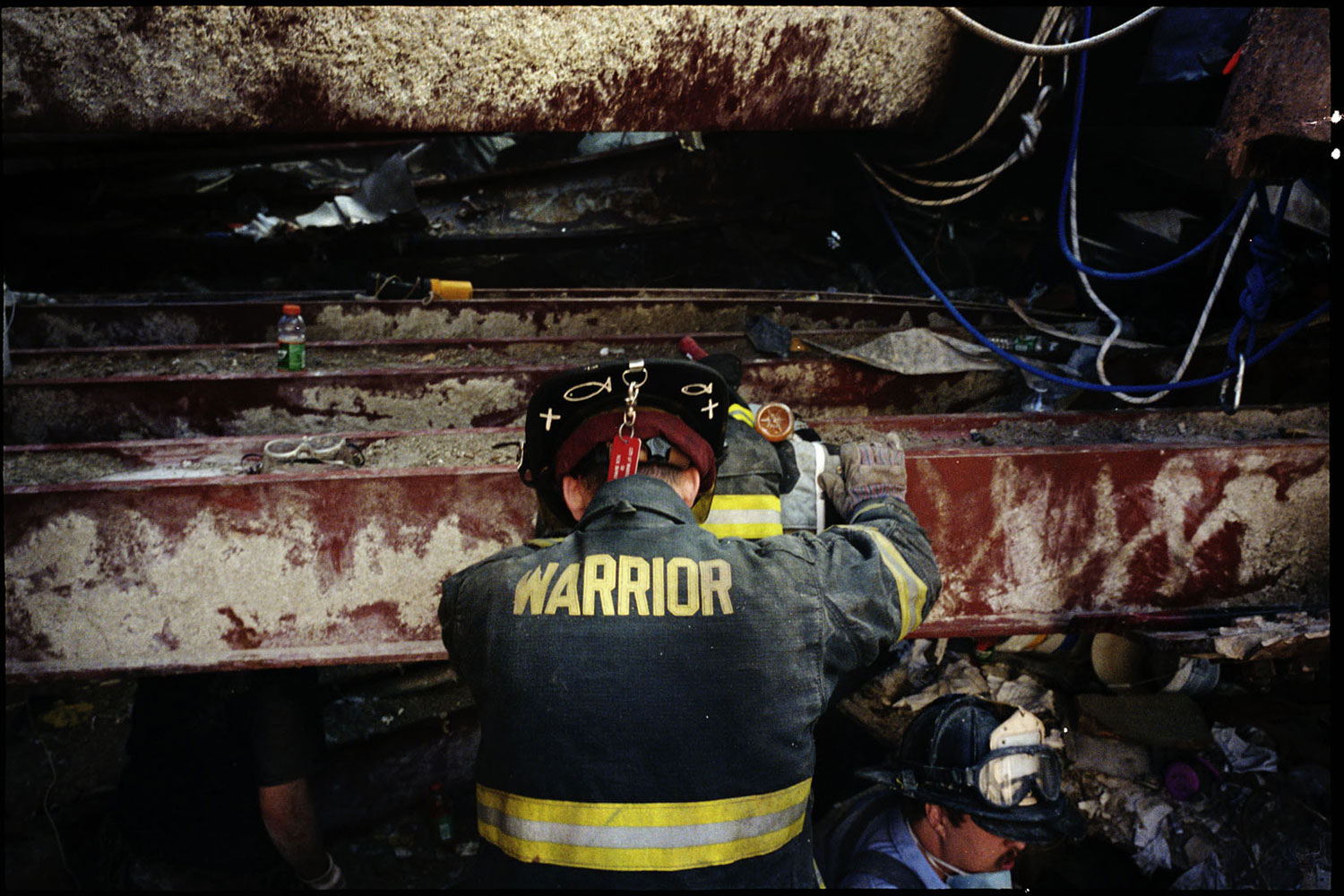

“The nights were intense,” Sednaoui says. “We would be on our knees digging, lifting and filling up buckets. There wasn’t much talking. Each had a specific task and we were all working in silence, being as efficient as possible. Of course, we all wanted to find survivors, but I sadly realized after a few hours that the purpose was also to recover dead bodies. Once in a while we would pause so that a special team could sound check the ground in hopes of hearing a survivor trapped underneath our feet; In those moments, I would pull out my camera and take a few pictures of my team.”

A small selection of Sednaoui’s photographs of the search and rescue were published in the French newspaper Liberation as well as Talk magazine. Sednaoui never watched the video he shot that morning from his roof; he locked away his stills for almost 10 years, not wanting the images to be misused to illustrate articles in preparation of the Iraq war or be used to fuel hatred.

Several months ago, Sednaoui revisited his work with the intention of editing and donating images to the National September 11 Memorial and Museum. He was surprised by the number of pictures he had taken—more than 500 over three nights. Not only do Sednaoui’s photographs fill a void in terms of what was documented at Ground Zero (the museum did not have a photographic record as large as Sednaoui’s from those first nights of search and rescue), but his images are unlike any others taken at the time. Throughout his career, Sednaoui has often shot with panoramic cameras to capture more than can be photographed within a traditional frame. He sometimes replicated this approach manually as he captured the burning towers and Ground Zero, panning horizontally and taking individual frames that he would later be able to stitch together. The result of Sednaoui’s process is a giant virtual negative that expands the frame and increases its detail. At the 9/11 Memorial, this enhanced detail will enable one of the images to be enlarged, so visitors can get a greater sense of the scale of the damage while revisiting the intense and inspiring search for those who died.

Here, TIME publishes Sednaoui’s Ground Zero search and rescue images (many of them for the first time) alongside the e-mails Sednaoui sent to his friends each time after coming back from Ground Zero. His incredibly personal e-mails, which now almost read as journal entries, offer some insight into his emotional experience as part of the search and rescue team. Reading through his correspondence now, his account is all the more powerful as it is not recalled from memory but was written in real-time in the immediate aftermath of 9/11.

<< Subj: Stephane in NewYork

Date: Tue, 11 Sep 2001 10:56:50 PM Eastern Daylight Time

Hello my dear friends, all in different countries.

I think that by now most of you have heard about the terrible attack on the twin towers in NY.

I am doing a group email because I am quite exhausted and can’t answer one by one to the friends that have contacted me. I spend the beginning of the day watching the horror from my roof and the rest of the day with a group of friends trying to volunteer, but too much fire and explosion still, too dangerous so we could do nothing.

Big big kiss to everybody

Stephane >>

<< Subj: New York part 2

Date: Sat, 15 Sep 2001 4:36:35 AM Eastern Daylight Time

Hello my friends

Again I do a group email to answer your emails or to update you.

The past two days have been hard. I spent the nights of the 12th and 13th at Ground Zero helping “Search & Rescue” to dig and remove all the debris. There are probably 2000 people down there, all Firemen, Policemen, Army. We are on our knees digging with our hands in the burned papers, dust, removing huge pieces of metal and concrete. What you see on TV is the outside, the heart of the disaster is apocalyptic, it is mad, there is so much to do, we work around the two mountains of debris where we still hope to find people alive. Sometimes we hear somebody yelling “QUIET”. All the rescuers stop working and for few minutes we stand there, not moving anything. It means that a team heard a sound from underneath, or spotted a possible pocket where somebody may still be alive. For a few minutes we hope and wait but every time it is a disappointment, as they find no signs, and we start to dig again. In those moments when the searches take a halt, I grab my little camera and do few pictures of the team I am working with.

There is still hope to find people.

This afternoon was my first “Normal”

… >>

<< Subj: New York part 3

Date: Sun, 16 Sep 2001 10:53:04 PM Eastern Daylight Time

Hello all my friends

Yesterday I was so tired that I sent an unfinished email by mistake.

So to continue my story

Friday morning, the 14th, I came back around 4 a.m. at home, after few hours of sleep I went to process the pictures I had done during the “silent pause” at Ground Zero. Throughout the day I had a really hard time going to the lab, walking in the streets, everybody was living their life nearly as normal, so normal that it made me feel sad and out of place.

At the end of the day, I went to dinner in my street and I didn’t understand why few waiters kept coming to talk to me, finally I understood that it was because I looked so lost that they wanted to pull me out of my sad thoughts. I was not sad, I was just a little confused. Really it is very hard to be active at the WTC and then to be back in the normal world where people are having a good time. It is odd. The waiter’s thoughtful attention worked for a while. Later I had to go to the hospital, it was already midnight and I had waited all that time to treat the big swollen rashes that were all over my left arm, a reaction to something I had been in contact with while digging at Ground Zero with bare arms. When I arrived at the Beth Israel Medical Hospital, I saw hundreds of laser copies taped on the walls, all from families searching for their relatives. That was really really hard. I was starting to break down. The doctor told me I had a rash, an allergy, nothing more, so that was good news but before I had the time to really ask any questions they injected me a very powerful drug that made me completely stoned! It was mad, I left the hospital walking like if I was drunk, not being able to really control my moves, I came back home by walk, I live on Great Jones, and passing in front of the fire station opposite my building, I realized that the horror was not ending, they were sad laser copies messages also there but this time it was to inform us that 25 firemen from Great Jones company had died in the destruction of the towers.

I came back home crying. Then I started to write all of you an email and fell asleep in the middle of it. The day after, the 15th, I spend all day wondering if I should go back or not. I was probably still under the effect of the drug because I kept forgetting everything, any decision was taking four times longer than normal and I found myself in a room wondering why I ended there. I didn’t want to go back to the WTC because I was not sure if it was the drug or if I was in a state of shock. I decided that I will not go that Saturday night and when I was going to bed a friend called me to tell me he had found a way for me to get in. I did a quick nap, and it worked, I woke up, put all my construction worker’s gears (I now have the complete outfit) and left at night in the direction of the WTC.

I have seen the attack from my terrace, “live,” I absorbed all the horror and I think I would go mad trying to act like if everything is OK, I would explode. I have to digest all this very slowly. At this point I don’t know what else to do besides going one more time to the site to help. The feeling to be so necessary, so useful there, is so intense and raw that it is hard for me to find any similar necessity in my normal life.

I know that by tomorrow Monday I’ll have to get back to my work because I won’t be necessary anymore down there, there is very little chance to find more people alive and to reach them requires only very few highly professional teams, at 9:30 they are closing the site to all volunteers. I also have a life to take care of and I am going to become a Daddy, which is definitely the most important thing for me (and kept me from taking the maximum risk down there). Helping the workers helped me to deal with the horror of the attack and accept the present and in a same way doing pictures, interpreting it through my vision, helped me to deal with the memories, what is coming up.

That email for sure is part of the same process, absorbing and being able to translate, to share with you my feelings and my experience. Being there at Ground Zero for me, my family and my friends. Reporting.

Voila, I really said all what I was holding

All the best to all of you

big kiss

Stephane

Stephane Sednaoui is a photographer and director. His formative fashion images and early portrait work were published in pop culture magazines The Face, Details, and in Vogue Italia. He has also worked as a documentary photographer covering the Romanian Revolution of 1989. Sednaoui has shot many album covers from Björk to Madonna, he has also directed more than 50 music videos for such artists as Massive Attack, Björk the Red Hot Chili Peppers and U2. In 2005, Palm Pictures published a retrospective of his video work, The Work of Director Stéphane Sednaoui. Sednaoui lives in Paris and New York.

To visit TIME’s Beyond 9/11: A Portrait of Resilience, a project that chronicles 9/11 and its aftermath, click here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com