Update, November 2013: Robert Nickelsberg’s work from Afghanistan has been compiled into a new monograph, Aghanistan: A Distant War, published by Prestel. For more information on the book, author signings and related multimedia presentations visit afghanistan.robertnickelsberg.com.

Afghanistan is a hard place to enter and even harder to leave. Everything in Afghanistan, the geography, the weather, the tribesmen, all conspire to keep out unwanted visitors. And once you’re inside this labyrinth of stone, it’s nearly impossible to find your way out. Dust storms besiege Kabul’s airport, blizzards close the mountain passes and bandits or Taliban fighters (it’s hard to tell them apart) ambush the roads.

Ask the British how hard it is to leave Afghanistan. During their infamous retreat from Kabul in 1842, only one survivor out of 17,500 soldiers and camp followers staggered out of the Kabul Gorge alive. Ask the Soviets, who fared nearly as badly. And if history is any judge, the Americans won’t face an easy departure, either.

Photojournalist Robert Nickelsberg has also found it impossible to leave. Since he first trekked into Afghanistan with the mujahedin in 1988, Nickelsberg keeps going back. He does so out of curiosity, duty and obsession. He was there for the Soviets’ withdrawal—flowers for tank gunners until the Red Army rumbled into the hairpins of the Hindu Kush and fell prey to ambush. He was there for the vicious civil war that broke out when the Soviet-backed regime fell apart in 1992 and Afghanistan’s ethnic groups, the Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, and Uzbeks turned snarling on each other. (And may do so again, after NATO forces depart.)

Nickelsberg was there for the Taliban’s conquest of Afghanistan, their swift fall after the U.S.-led invasion and the Taliban’s rise again. “The Americans didn’t grasp how complex this is,” Nickelsberg says, “The soldiers come and go so fast they barely have time to figure out where the sun rises and sets.”

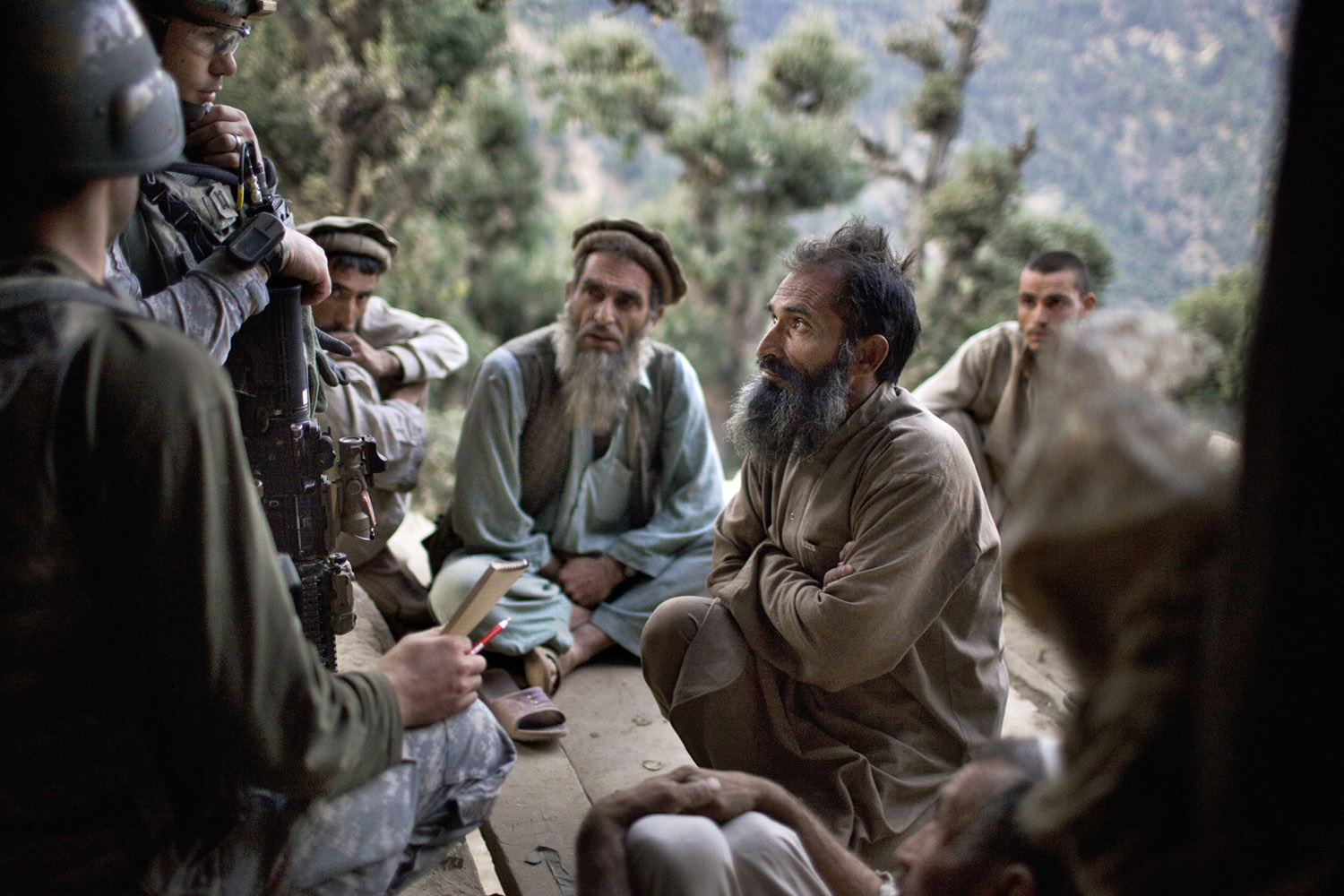

His photos bear witness to that complexity, to the savage beauty of Afghanistan and its people. His photos are spare, intense. Every image is stripped down to the essential drama, and in doing so Nickelsberg illuminates the pivotal moments in Afghanistan’s chronology of war and the brief, quiet moments in between, when Afghans catch their breath.

When I first ventured into Afghanistan in 1990, I sought out Nickelsberg, thinking, unwisely, that he would keep me from getting shot at. It was quite the reverse. Nickelsberg reacts to gunfire like a bird dog to the rustle of quail. He led me straight into the Kabul Gorge, where in my imagination, ghosts from the British massacre flitted in the ravine’s bottomless shadows and menace was ever-present. Nickelsberg was looking for Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, one of Afghanistan’s more sadistic, and enduring, warlords. Luckily, we didn’t find Hekmatyar’s cutthroats that day, though a year later they would murder my Afghan translator. Following Nickelsberg into dangerous situations, mortar barrages, gun-battles, sieges and ambushes, became a pattern for the next 16 years of my life while I covered Afghanistan. He would get us into jams but he would always know how to get us out. Nickelsberg has longer legs than I do but, in retreat, I always out-ran him.

Many journalists love to dress up like Afghans, with the long tunic, the baggy pantaloons and the flat woolen caps known as pakools. They’re like giddy children going off to a costume party. Not Nickelsberg. He dresses for war as if going for a brisk walk in the Vermont hills, his hair as clipped as a military officer’s, perfectly parted. In the midst of Afghanistan’s chaos, Nickelsberg always kept his composure, his flinty style. And this reflects in his photography: there is a sharpness to his composition, a rigorous clarity.

Most photographers are captivated by swift light, motion and color, which Afghanistan has aplenty. But Nickelsberg stuck around. He bothered to learn about the people he portrays so keenly, the reasons why they laugh and cry—and kill. His photos aren’t just war and gore—though, undeniably, that’s part of Afghan history—but also the quotidian. Two shots in particular, young men dancing at a picnic in Babur’s gardens and warrior Ahmed Shah Masood sitting with his companions, have the delicacy of Mogul miniatures.

Nicklesberg’s hard-won knowledge of Afghanistan gives a rare depth to his photos. He wasn’t just snapping a pretty picture. He knew he was capturing Afghanistan’s history, and ours.

Robert Nickelsberg was a TIME magazine contract photographer for 25 years and was based in New Delhi from 1988 to 2000. During that time, he documented conflicts in Kashmir, Iraq, Sri Lanka, India and Afghanistan. Currently represented by Getty Images, he is working on publishing a book of his photographs from Afghanistan.

Tim McGirk, a former TIME bureau chief, has been covering Afghanistan on and off since 1990, when he first ventured in with photojournalist Robert Nickelsberg. McGirk is currently managing editor of the University of California at Berkeley’s Investigative Reporting Program.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com