In Kiev’s Independence Square, the aftermath of a bloody revolution has left behind a strange beauty. Red roses adorn piles of charred black tires. A rainbow of votive candles lay before heaps of rusted metal, burnt wood, and other debris—remnants of barriers built by anti-government protesters against thuggish security forces. Beneath a lamp post punctured by bullet holes—snipers—lies the photo of a smiling young man and a splendid pile of flowers in his memory. In an auditorium at Kiev’s city hall, now manned round-the-clock by activists who feel their work remains incomplete, a young man in a bulletproof vest plays a gentle classical piece on a white piano.

These contrasts also stand in for Ukraine’s political reality, now a mix of wreckage and blooming hope three weeks after massive protests overthrow an authoritarian president who had spurned Europe for Russia’s orbit. An interim government has now replaced the reputedly corrupt Viktor Yanukovych, and elections are scheduled for May. But the economy is in crisis and the parliament is still packed with dubious characters. Talk of war hangs in the air like the smoke from the barrel fires warming the activists and self-defense volunteers still camped on the square, who say their work is unfinished. Russian President Vladimir Putin has seized the Crimean peninsula, and may have designs on other parts of Ukraine’s pro-Russian east. Kiev’s anxious residents are left to wonder whether their future holds more flames than flowers.

Elena, as we’ll call her, is a 25-year-old lawyer here. She grew up in the pro-Russian east but studied in the UK on a scholarship. Smartly dressed in a grey tweed jacket and black-framed glasses, Elena estimates that she filled two dozen Molotov cocktails during the protests. She also volunteered in a makeshift hospital, witnessing injuries like she’d never seen before.

Elena never imagined that Ukraine’s fate could grow so precarious. “I never thought I would wake up every day happy just that there is no war,” she says. Things she’s always taken for granted—Internet service, electricity, basic security—now all seem contingent on Putin’s unknown intentions.

“You know, when people are crazy you are not sure what they will do,” says Anna Shyshko, a 30 year old legal secretary smoking a cigarette on the square one recent afternoon. She hopes that the West will take more decisive action than it did as protesters were being gunned down last month.

“On Facebook all the time they’re saying the U.S. and European Union worried much too long,” she says. “While they were shooting people, [the West was] saying that they are worried about our country. But it took too long.”

For now, Kiev is mostly peaceful, a seemingly happy European city. Coffee booths are plentiful on the streets. The downtown Porsche dealership is still open, as is a men’s luxury clothing store named Billionaire—destinations, perhaps, for Yanukovych’s oligarch allies. At an upscale karaoke bar, party people smoked hookahs and belted out maudlin ballads into the small hours.

But some here seem girded for more fighting. Around the square, known here as the Maidan, men in camouflage uniforms who describe themselves as self-defense forces are camped out in dozens of tents. Some fly the red and black flag of the Ukrainian People’s Army, a World War II-era anti-Soviet partisan force; it’s a common sign of affiliation with the modern nationalist, far-right Pravy Sector. (The UPA’s alliance with the Nazis remains a subject of intense debate.) After midnight a few nights ago, a pair of young men with mohawks patrolled a main street with baseball bats; they identified themselves as members of Spilna Sprava, another right-wing nationalist group.

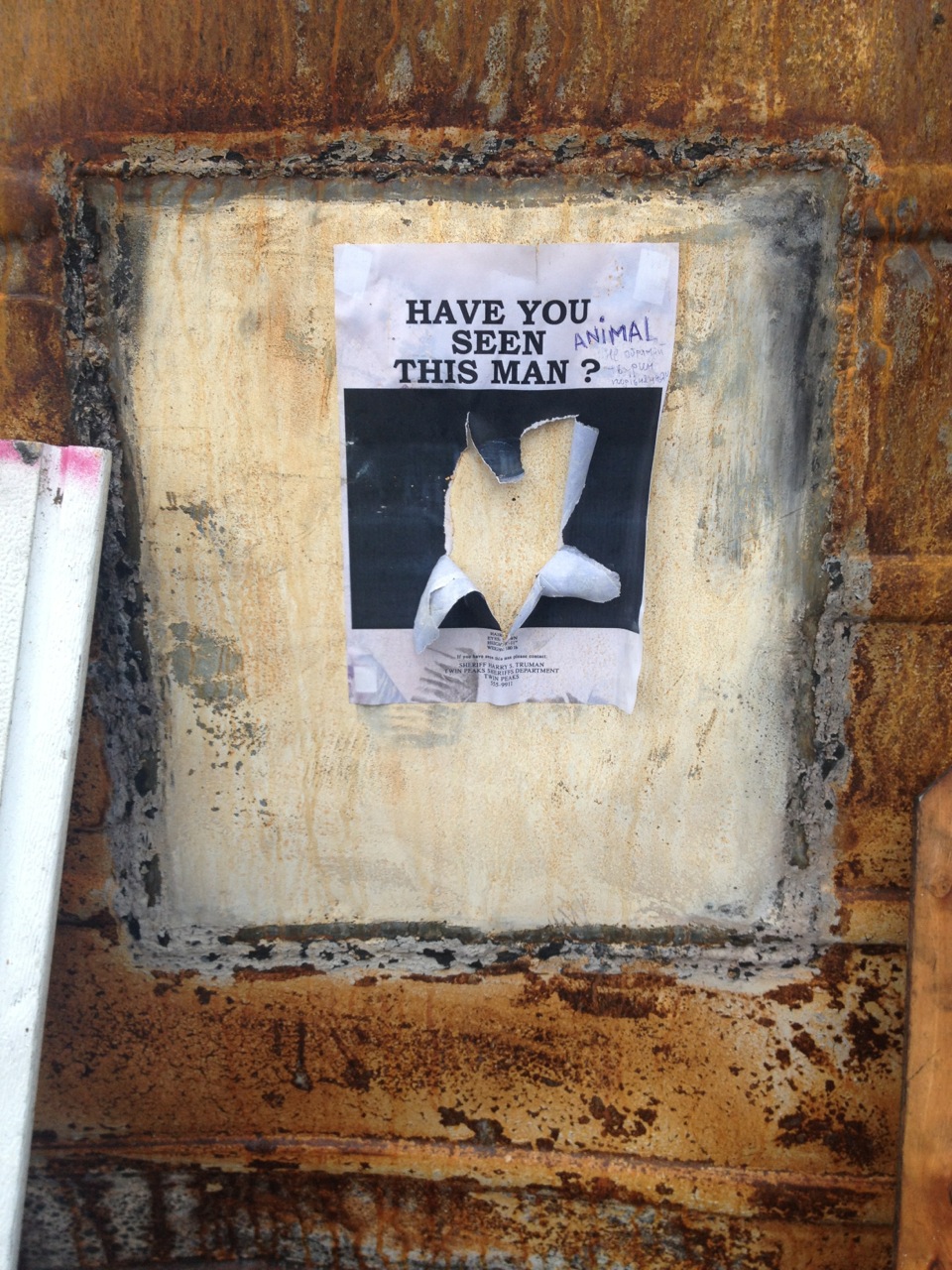

On a rise above the square lay a pair of overturned burnt-out vehicles that likely belonged to the now-vanquished Berkut security forces. “Have You Seen This Man?” asks a sign taped to one of them. But there is no way to tell: the man’s photo has been torn out. Next to the empty space someone has scrawled the word ANIMAL.

A short walk from the Maidan to the Dnipro river bank offered more unsettling sights. Crates of Molotov cocktails fashioned from beer bottles lay unattended near the National Philharmonic Building. In a grand park overlooking the river, access to a large Soviet-era monument to the unity of Ukraine and Russia has been barricaded— presumably to prevent defacement of a statue representing an ideal that many here now despise.

A few hundred yards away towers Vladimir. Not Putin, but Vladimir the Great, a local ruler who Christianized the region a thousand years ago. (This was after he rejected Islam, in part, because it forbids drinking: “We cannot exist without that pleasure,” he allegedly declared.)

Behind the statue is a well-kept, tree-lined public park, where the other Vladimir’s shadow loomed. A group of perhaps two dozen men in makeshift paramilitary uniforms were training here for combat. Some concealed their faces behind balaclavas; several wore scarves in the UPA’s red and black. One group practiced hand-to-hand fighting—faux punches, arm twists, leg sweeps. Another, wielding what appeared to be fake wooden pistols and rifles, took positions behind trees. They would duck out, then quickly swerve back again, taking shots at their imaginary enemy.

None spoke English. One man in a balaclava insisted that a reporter stop taking photographs. Two others encouraged more pictures, and the three fell into a squabble. Meanwhile, a young couple out for a walk in the park pushed a stroller past the men practicing hand to hand combat. The trainees politely stood aside as the infant rolled by.

So it goes in these strange days of Kiev’s unfinished revolution.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com